Por William Lane Craig

RESUMEN

Wes Morriston argumenta que, si incluso consideramos que una serie interminable de eventos es meramente potencial, en lugar de actualmente infinita, aún no se ha establecido una distinción entre una serie de eventos sin comienzo y una serie interminable, que es relevante para los argumentos en contra de la posibilidad metafísica de un número infinito actual de cosas: si una serie sin comienzo es imposible, también lo es una serie sin fin. El éxito del argumento de Morriston, sin embargo, depende de rechazar la caracterización de una serie interminable de eventos como un infinito potencial. Resulta que, según su propio análisis, es de vital importancia si la serie de eventos es potencial a diferencia de actualmente infinita. Si es razonable mantener que una serie infinita de eventos es potencialmente infinita, mientras que una serie sin comienzo es actualmente infinita, entonces se ha establecido una distinción relevante para cualquier persona que piense que un infinito actual no puede existir.

I

Según Wes Morriston, el corazón de su paper[i] se refiere a dos afirmaciones:

(i.) que una serie interminable de eventos es meramente un potencial infinito.

y

(ii.) que esto establece una distinción relevante entre el pasado sin comienzo (que supuestamente es imposible) y un futuro sin fin (que es claramente posible).

Nos dice que “argumentaré que no se ha establecido una distinción relevante”. La declaración de Morriston hace evidente que su crítica se dirigirá a la segunda afirmación expuesta arriba. Para tener éxito, tal crítica debe otorgar (i), al menos por el bien del argumento. Morriston debe mostrar que incluso si una serie interminable de eventos es meramente potencial, en lugar de actualmente infinita, entonces no se ha establecido una distinción relevante entre las dos series.

Una lectura cuidadosa del artículo de Morriston revela, sin embargo, que fracasa en su objetivo, a mitad de su trabajo, comenzando en la sección titulada “¿Un infinito meramente potencial?”, Morriston pasa a atacar (i) en lugar de concederlo. El éxito de su argumento viene a depender de rechazar la caracterización de (i) como una serie infinita de eventos siendo un infinito potencial. Resulta que, según su propio análisis, es de vital importancia si la serie de eventos es potencial a diferencia de actualmente infinita. Si es razonable mantener que una serie infinita de eventos es potencialmente infinita, mientras que una serie sin comienzo es en actualmente infinita, entonces se ha establecido una distinción relevante para cualquier persona que piense que un infinito actual no puede existir.

El ataque de Morriston a la infinitud potencial de una serie interminable de eventos es, por lo tanto, de un interés mucho más amplio que las preocupaciones de la teología natural, ya que virtualmente todos los filósofos que defienden una teoría del tiempo dinámica o A, sostienen que la serie de sucesivamente ordenada e isócrona de eventos posteriores a algún evento denominado es potencialmente infinita.

II

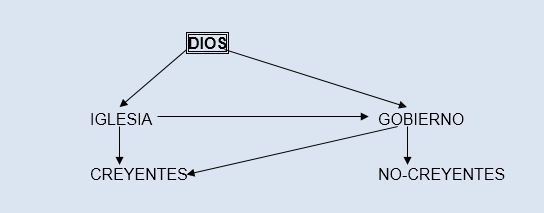

El argumento de Morriston, antes del cambio crucial mencionado anteriormente, es fatalmente ambiguo.[ii] Hay dos formas en que una serie temporal de eventos isócronos que tiene un comienzo puede ser interminable: (i) podría ser actualmente infinita, es decir, compuesta de un número infinito actual de eventos; (ii) podría ser potencialmente infinita, es decir, compuesto por un finito, pero siempre creciente número de eventos con el infinito como límite. La segunda respuesta implica una teoría A del tiempo según la cual el devenir temporal es una característica objetiva de la realidad, mientras que la primera respuesta está asociada, naturalmente, con una teoría B según la cual todos los eventos en el tiempo están a la par de los factores ontológicos.

Entonces, con respecto a la ilustración de Morriston de dos ángeles que comienzan a alabar a Dios para siempre, un teórico A coincidirá de todo corazón con su afirmación: “Si preguntas: ‘¿Cuántas alabanzas se expresarán?’, la única respuesta sensata es infinitamente muchas”—es decir, muchas, pero potencialmente infinitas. Si esta respuesta es permitida por el teórico A, entonces los argumentos supuestamente paralelos de Morriston colapsan. Dios podría haber dejado espacio para un número infinito de alabanzas potencialmente infinitas por parte de un tercer ángel, en cuyo caso se “agregarán” infinitamente muchas alabanzas, y las alabanzas de los tres ángeles se dirán en la misma cantidad de tiempo potencialmente infinita. No hay absurdo allí, ya que el número de alabanzas dichas por los ángeles siempre será finito, aunque aumente hacia el infinito como límite. O, de nuevo, si Dios determinó que los ángeles se detuvieran después de la cuarta alabanza o si un ángel fuese silenciado, se podrían evitar muchas alabanzas infinitas potencialmente, pero en un caso solo expresarán cuatro alabanzas mientras que en la otra se dirán infinitas potencialmente. De nuevo, no hay absurdo, ya que el infinito es simplemente potencial. No se puede decir nada paralelo de una serie de eventos sin principio, ya que, dada la asimetría de lo temporal, el pasado no puede ser potencialmente infinito, porque entonces tendría que ser finito, pero creciendo en una dirección hacia atrás.

Si se permite tal respuesta, el teórico A—como debe ser si Morriston tiene éxito en demostrar que interpretar una serie interminable de eventos como potencialmente infinitos no es relevante para el argumento—está claro que los casos de Morriston no están completamente paralelos a una serie de eventos sin principio. A medida que se aclara aún más en los argumentos del kalam para la finitud del pasado basada en la imposibilidad de formar un infinito actual mediante una adición sucesiva,[iii] la asimetría del tiempo marca una enorme diferencia metafísica entre el pasado y el futuro en una teoría A del tiempo. Quizás la oración más reveladora en el artículo de Morriston sea su desconcertada pregunta: “¿Qué diferencia podría hacer un simple cambio de tiempo?”

III

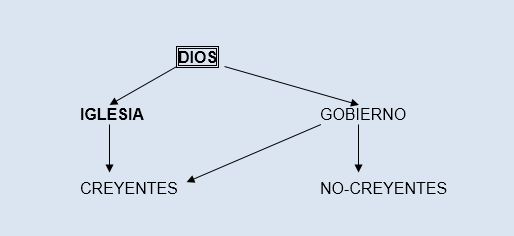

Al darse cuenta de que el teórico A insistirá en que una serie interminable de eventos es propiamente un potencial en lugar de un infinito actual, Morriston, en la segunda parte de su artículo, recurre, en contra de su propósito declarado, a desafiar la afirmación de que una serie interminable de eventos es simplemente potencialmente infinita. Él pregunta: “¿Está claro que la serie interminable de alabanzas futuras previstas es un potencial, en lugar de un infinito actual?” “Dada la realidad del devenir temporal, ¿deberíamos decir que la serie interminable de eventos que he previsto es un infinito meramente potencial?”

Para justificar una respuesta negativa a esas preguntas, Morriston malinterpreta el punto de vista del teórico A de una manera perversa pero interesante. Cuando el Teórico A expresa la afirmación (i) arriba antes mencionada, la serie interminable de eventos de la que está hablando es la serie actual de eventos que han ocurrido. Pero como Morriston deja en claro, está hablando de una serie que, en la teoría A, no existe en ningún sentido, es decir, la serie de eventos que aún no han sucedido. Así que Morriston dice:

Como lo he previsto, la serie de alabanzas futuras no está “creciendo” en absoluto. A medida que cada alabanza se hace presente, se elimina de la “colección” de aquellas que aún están por venir. La colección de alabanzas futuras es, por así decirlo, miembros perdidos.

Esto golpeará a un teórico A como una extraña ontología, al menos a la que el teórico A no está comprometido de ninguna manera. No existe una serie como la que Morriston imagina, como tampoco existe una serie de eventos que se previnieron, que aumenta constantemente a medida que pasa el tiempo. Morriston no ha demostrado que la afirmación (i) sea falsa con respecto a la serie que el teórico A tiene en mente, porque el referente de la frase “una serie interminable de eventos” y “un futuro sin fin” en las afirmaciones (i) y (ii) es una serie diferente de la serie que Morriston está considerando.

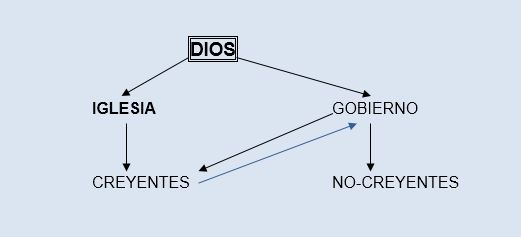

Morriston niega que esté hablando de ontología. Él dice que podría reformular su afirmación de que la colección de verdades temporales futuras sobre las alabanzas de los ángeles está perdiendo miembros. Pero luego está hablando de ontología, ya que tal reformulación parece presuponer que las verdades son objetos abstractos, lo que no ha sido justificado. Morriston necesita encontrar algo que sea parte de la realidad que sea actualmente infinita en cantidad para hacer una analogía con una serie sin comienzo de eventos pasados. Morriston luego vuelve a su sugerencia de que, en lugar de eventos futuros, que en una teoría A del tiempo no son parte de la realidad, consideramos verdades temporales en el futuro o hechos temporales correspondientes. Pero este movimiento hace dos suposiciones injustificadas: primero, el platonismo con respecto a las proposiciones y, segundo, la infinitud actual de proposiciones o hechos. Si aceptamos estas suposiciones, no hay necesidad de apelar a verdades temporales en el futuro para designar una infinitud actual de proposiciones, ya que para cada proposición p existe la proposición adicional de que Tp, o que es verdad que p. El finitista, por lo tanto, negará el platonismo con respecto a las proposiciones, considerándolas como ficciones útiles, o negará que haya un número infinito de proposiciones, ya que, dado que el conocimiento de Dios no es proposicional, las proposiciones son el subproducto de la intelección humana y, por lo tanto, potencialmente infinitas en número, ya que llegamos a expresar de manera proposicional lo que Dios sabe de una manera no proposicional.

Morriston reitera su intuición de que el número de alabanzas angelicales que se dirán en una serie interminable es actualmente infinito. Pero las únicas alabanzas que son actuales son las que se dicen, y siempre serán finitas en número. No se dirá un número actualmente infinito de alabanzas. Considere los ejemplos más familiares del potencial infinito en la división espacial y la suma. Hay una enorme diferencia entre tomar una línea espacial como una composición de puntos densamente ordenada y tomarla como no compuesta de puntos, sino potencial e infinitamente divisible. En la segunda postura, se puede continuar dividiendo una línea sin fin, pero no se puede hacer un número actualmente infinito de divisiones. Estas son posturas completamente distintas de la naturaleza del espacio, y una no puede colapsarse en la otra. O, de nuevo, si el universo es finito (debido a que el espacio tiene una curvatura positiva) pero se expande sin cesar, el volumen del universo es potencialmente infinito, pero no se volverá actualmente infinito. Hay un mundo de diferencia entre los modelos del universo en los que el espacio es actualmente infinito en extensión y los modelos en los que el espacio se expande constantemente pero siempre es finito.

Del mismo modo, en las ilustraciones de Morriston, lo que es real o actual siempre es finito. Entonces, en respuesta a la pregunta de Morriston, “¿Cuántas alabanzas se dirán?”, Debemos responder, “Potencialmente infinitas,” y distinguir esto de la pregunta, “¿Cuál es el número de alabanzas en la serie de alabanzas futuras?”, la respuesta a la cual es “Ninguno”.

Morriston insiste en que, en una teoría A del tiempo, los eventos pasados tampoco existen, por lo que la no existencia de eventos futuros no hace ninguna diferencia real. Pero a pesar de confesar un poco de perplejidad sobre el concepto del potencial infinito como límite,[iv] Morriston parece preparado para admitir que la serie de eventos que han sucedido es solo potencialmente infinita en la dirección después que (later than). Además, está claro que nada paralelo puede decirse con sinceridad sobre la serie de eventos que han sucedido en la dirección antes que (earlier than). El número de eventos que ocurrieron antes que cualquier evento dado, por lo tanto, solo puede ser finito o actualmente infinito. En una teoría A del tiempo, la serie temporal de eventos comprende todo lo que ha sucedido y nada más. Note bien el uso del tiempo pretérito perfecto en esta caracterización. El tiempo verbal pretérito perfecto de “ha sucedido” cubre cada vez hasta el presente y, por lo tanto, incluye cada evento pasado y presente. Todo lo que ha sucedido se ha actualizado. Como lo expresaron los medievales, estos eventos han salido de sus causas y, por lo tanto, ya no tienen potencial. El mundo actual incluye tanto lo que existe como lo que existió. Pero los eventos que aún no han tenido lugar, siendo pura potencialidad, no son, en una visión dinámica del tiempo, parte del mundo actual.[v]

La distinción ontológica entre el pasado y el presente, por un lado, y el futuro, por el otro, es especialmente evidente en los puntos de vista “bloque creciente” del tiempo, como el enunciado por el medio (middle) C. D. Broad y defendido por el colega de Morriston, Michael Tooley. Un defensor del argumento kalam que acepta la visión de bloque creciente no tiene dificultad en diferenciar la actualidad del pasado de la potencialidad del futuro. Mi afirmación es que la existencia sin tiempo del bloque pasado de eventos no es una condición necesaria de la actualidad del pasado. Incluso si los eventos pasados no existen, siguen siendo parte del mundo real de una manera que los eventos futuros no lo son, ya que el mundo real comprende todo lo que ha sucedido.

IV

En conclusión, parece claro que Morriston no ha tenido éxito en el propósito central de su artículo, a saber, mostrar que incluso si una serie interminable de eventos es solo potencialmente infinita, ese hecho no establece una distinción relevante entre el pasado sin principio y un futuro sin fin. En cambio, se vio obligado a pasar a argumentar que una serie interminable de eventos no puede considerarse potencialmente infinita. Pero su argumento malinterpretó seriamente la Teoría A del tiempo, sustituyendo una serie imaginaria de eventos por la serie de eventos en curso que realmente han sucedido.

Notas:

[i] Wes Morriston, “Beginningless Past, Endless Future, and the Actual Infinite,” Faith and Philosophy.

[ii] Aunque no estoy completamente contento con la reconstrucción de Morriston de mi argumento a favor del finitismo, lo dejé pasar. En lugar de hablar de mundos alternativos posibles, debería hablar en términos de condicionales contrafácticos. Si todos los demás huéspedes en el Hotel Hilbert se fueran, ¿cuántos quedarían? El experimento mental no depende de la verdad del antecedente. Creo que hay contrafácticos no trivialmente verdaderos con antecedentes imposibles, por ejemplo, “Si Dios no existiera, el universo no existiría”.

[iii] La diferencia entre la potencialidad del futuro y la actualidad del pasado emerge con especial claridad en los argumentos del Kalam para el comienzo del universo, basados en la imposibilidad de formar un infinito actual mediante sumas sucesivas. Por ejemplo, al-Ghazali nos invita a suponer que Júpiter y Saturno orbitan alrededor del Sol de tal manera que por cada órbita que Saturno completa, Júpiter completa dos. Cuanto más orbitan, más se queda atrás Saturno. Si continúan orbitando para siempre, se acercarán a un límite en el que Saturno está infinitamente lejos de Júpiter. Por supuesto, nunca llegarán a este límite. Pero ahora cambie la historia: suponga que Júpiter y Saturno han estado orbitando el Sol desde la eternidad pasada. ¿Cuál habrá completado la mayor cantidad de órbitas? La respuesta es que el número de sus órbitas es exactamente el mismo, es decir, ¡infinito! Eso puede parecer absurdo, pero parece ser el resultado inevitable de la actualidad del pasado en oposición a la potencialidad del futuro.

[iv] Los límites juegan un papel esencial en el proceso matemático de diferenciación, uno de los pilares del cálculo. El límite de una determinada función f (x) es el valor de esa función cuando x se acerca a un número dado. Esto está escrito:

lim f (x) = L

x → a

que se lee, “A medida que x se acerca a a, el límite de f (x) es L.” A veces uno está interesado en encontrar el límite de una función a medida que el valor de a aumenta indefinidamente, en cuyo caso se sustituye a por el signo del potencial infinito “∞”:

lim f (x) = L

x → ∞

En tales casos, se dice que estamos determinando el límite “al” infinito. A veces, el valor de una función aumenta indefinidamente a medida que las entradas se acercan a un cierto número, en cuyo caso el límite de la función es infinito:

lim f (x) = ∞

x → a

En ninguno de los casos el infinito es un número, como lo es ℵ0. En las ilustraciones de Morriston, tanto el valor de a como el límite de la función f (x) son ∞. Entonces, por ejemplo, si por cada alabanza pronunciada por un ángel hay dos pronunciadas por el otro,

lim f (x) = 2x = ∞

x → ∞

A medida que x se aproxima al infinito, también lo hace la salida de la función 2x. Significativamente, el valor de la función f (a) no tiene relación alguna con el valor o incluso con la existencia de un límite a medida que x se acerca a a, es decir, “a” a. Por lo tanto, en la ilustración de Morriston no estamos hablando del valor f (∞). El infinito es simplemente acercado, no alcanzado. Entonces, si comparamos el número de alabanzas ofrecidas por los ángeles, encontramos que cada vez más divergen:

lim g (x) = 2x – x = ∞

x → ∞

Pero ahora contrasta el caso de dos ángeles que alaban a Dios en una proporción de 2: 1 desde la eternidad pasada. En este caso, como en el caso de Saturno y Júpiter en la ilustración de al-Ghazali mencionada en la nota 3, se ha alcanzado el infinito; se ha pronunciado un número actualmente infinito de alabanzas. En este caso, de hecho, nos preocupa el valor f (a), y solo puede ser 2⋅ℵ0 = ℵ0.

[v] La lección de la paradoja de McTaggart es que, si nos tomamos el tiempo en serio, no puede haber una descripción máxima de la realidad como se imagina en la semántica de los mundos posibles, que proporcionan descripciones puramente atemporales de cómo podría ser el mundo. Para un intento de introducir el tiempo en la semántica de mundos posibles, ver William Lane Craig, The Tensed Theory of Time: A Critical Examination, Synthese Library 293 (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2000), pp. 208-10.

William Lane Craig es un filósofo analítico y teólogo cristiano bautista estadounidense. El trabajo filosófico de Craig se enfoca en la filosofía de la religión, la metafísica y la filosofía del tiempo. Su interés teológico se encuentra en los estudios del Jesús histórico y en la teología filosófica.

Blog Original: http://bit.ly/2Tbzwid

Traducido por Jairo Izquierdo