By William Lane Craig

SUMMARY

On a deflationary view of truth, the truth predicate does not attribute a property of explanatory meaning to assertions. The truth predicate is simply a semantic ascent device, by means of which we talk about an assertion rather than assert that assertion. Such a device is useful for blind truth claims to statements that we cannot state explicitly. Such a view is compatible with truth as correspondence, and thus does not entail postmodern anti-realism, since the assertions directly asserted are descriptive of the world as it actually is. Getting rid of propositional truth has the advantage of ridding us of abstract truth bearers, which God has not created.

A central element of biblical theism is the conception of God as the only self-existent being, the Creator of all reality apart from Himself. God alone exists a se ; everything else exists ab alio . God alone exists necessarily and eternally; everything else has been created by God and is therefore contingently and temporally finite in its being.

The classical theist doctrine of divine aseity faces its most significant challenge in the form of Platonism, the view that there are uncreated, indeed uncreable, abstract objects, such as mathematical objects, properties, and propositions. In the absence of the formulation of a defensible form of absolute creationism, which has not so far occurred, the orthodox theist will want to rid his ontology of such abstract objects. [1]

One of the hardest to avoid is probably propositions. The orthodox theist is committed to objective truths about the world such as “God exists,” “The world was created by God,” “Salvation is available only through the atoning death of Christ,” and so on. Any postmodern or nihilistic denial of truth is theologically unacceptable. But if there are objective truths, then there must, it seems, be something that is true. But what could this be? The anti-Platonist can happily admit the existence of instances (tokens) of statements as truth-bearers, since these are concrete and clearly created objects. But what about a statement like “No human beings exist?” Wasn’t that true during the Jurassic Period? But how could it be true if there were no instances of statements at that time? And what about necessary truths like “No bachelor is married?” Isn’t that true in all possible worlds, even worlds in which only God exists? Tarski’s T-schema which establishes a material condition on any theory of truth

T. ” S ” is true if S ,

even if it has been established for a language L , it cannot reasonably be thought to take case statements of L as substitutes for S because the right-left implication of Tarski’s biconditionals seems clearly false: it is not the case, for example, that if the tyrannosaurus at time t and place l is eating a tracodont, then it is true that “The tyrannosaurus at t , l is eating a tracodont”, where it is a case (token) statement that is true. Considerations such as these might lead us to posit abstract propositions as our truth-bearers.

A neutralist view of quantification and reference can help us resist any ontological implications that such a move might seem to entail. [2] Neutralism challenges the traditional Quinean criterion of ontological commitment, according to which the values of the variables bound by the first-order existential quantifier or the referents of the singular terms in statements taken to be true must exist. Neutralism undermines the traditional indispensability argument for abstract objects by denying that quantification or reference to the abstract word in true statements commits its user to the reality of those objects.

Neutralism, therefore, eliminates much of the justification for Platonism with respect to abstract objects. For a neutral theory of reference allows us to assert truths about things that do not exist, that is, to assert claims about singular terms for which there are no corresponding objects, e.g.,

- Next Wednesday is the day of the faculty meeting.

- The whereabouts of the Prime Minister remain unknown.

- My doubts about the plan remain unassailable.

So even if we take clauses like “that snow is white” to be singular terms referring to entities to which truth is attributed, as in “It is true that snow is white” or alternatively, “That snow is white is true,” [3] we have not committed ourselves to the reality of the propositions. The neutralist can help himself with equanimity to judgments like “it was true during the Jurassic Period that there were no human beings” and “that no bachelor is married is necessarily true.”

It has been thought that a neutral theory of reference entails a denial of a correspondence theory of truth. For example, the most prominent proponent of neutralism, Jody Azzouni, thinks that to claim that mathematical statements are true even though mathematical objects do not exist entails a rejection of a correspondence view of truth. On a nominalist view, he thinks that since there are no mathematical objects, there can be no correspondence between mathematical truths and the world. So the success of mathematical theories, as well as their truth, must be due to something other than their correspondence to the world. He holds that “there is no property—relational or otherwise—that can be described as what all true statements have in common (apart from, of course, that they are all ‘true’).” [4]

But is that, in fact, the case? It seems to me that taking truth as a property of corresponding to reality does not require the kind of word-world relation that Azzouni assumes. [5] Too many philosophers, I think, are still in the thrall of a kind of picture theory of language according to which singular terms in true statements must have corresponding objects in the world. [6] I have argued elsewhere that such a view is quite mistaken. [7] The unit of correspondence, so to speak, need not be thought of as individual words or other subsentential expressions. [8] Rather one can take correspondence as obtaining between a statement as a whole (or the proposition expressed by it) and the world. Such a holistic correspondence is given by Tarski’s biconditionals. A deflationary view of truth, as Azzouni asserts it, need not be understood as anything other than the notion of truth as correspondence of the kind ” that S ” is true (or corresponds to reality) if and only if S. That is all there is to truth as correspondence, and it is wrong to look for correlates in reality for all the singular terms presented in S. [9]

Correspondence, so understood, need not commit us to the view that truth is a substantial property possessed by truth-bearers, even given its universal applicability to true claims. The key to this claim is obviously the adjective “substantial.” It is easy to think of insubstantial properties that all true claims have in virtue of being true—for example, being believed by God . As an omniscient being, God has the property of knowing only and all truths, so that every true claim has the property known by God . But that should not be taken to be a substantial property of true claims in the sense that it does no explanatory work. Similarly, every true claim has the property of corresponding to reality in the sense mentioned above, but that hardly seems like a substantial property of such claims. It is trivial that it is true that S if and only if S. In light of a neutral theory of reference, it seems to me that Azzouni needs to complement his deflationary view of truth with an equally deflationary view of correspondence.

Similarly, in a neutral logic, the quantification of objects in a postulated domain is not ontologically committed. For example,

- There have been 44 US presidents.

from this point of view, it does not commit us to a static theory of time according to which objects of the past exist in reality like present objects. Nor does the truth of

- Some Greek gods were also worshipped by the Romans, although under different names.

does not commit us to the reality of the gods. Nor does the truth of

- There’s a hole in your shirt.

It commits us ontologically to another object besides the shirt, namely, the hole in it.

From the fact that, for some proposition p , it is true that p , the neutralist is happy to infer that therefore “Some proposition is true” or “There is at least one true proposition,” because these existential generalizations carry no ontological commitment. Similarly, the neutralist can claim that “There are true propositions” and “Some propositions have never been expressed in language” without being committed to an ontology that includes propositions.

So neutrality about quantification and reference goes a long way toward removing any grounds for Platonism about propositions. Still, the neutralist who is an orthodox theorist, if pressed by an ontologist to say what he thinks about the existence of propositions in a fundamental sense [10] will confess that he thinks propositions do not exist, that there really are no propositions. Therefore, there really are no true propositions. How are we to understand such a denial in light of his previous claim that some propositions are true?

Here I think we can benefit from paying attention to Rudolf Carnap’s distinction between what he called “internal questions,” i.e. questions about the existence of certain entities questioned within a given linguistic framework, and “external questions,” i.e. questions about the existence of the system of entities posed from a point of view outside that framework. [11] Carnap does not explain what he means by a linguistic framework, but he characterizes it as “a certain form of language” or “way of speaking” that includes “rules for forming statements and for testing, accepting, or rejecting them.” [12] Accordingly, a linguistic framework can be taken to be a formalized language (or fragment thereof) with semantic rules interpreting its utterances and assigning truth conditions to its statements. [13] It is a way of speaking that assumes the meaningful use of certain singular terms governed by rules of reference.

Carnap illustrates his distinction by appealing to what he calls the “thing” frame or language. Once we have adopted the thing language of a spatiotemporally ordered system of observable things, we can ask internal questions like “How many things are on my desk?” or “Is the Moon a thing?” From such internal questions one must distinguish the external question of the reality of things. Someone who rejects the thing frame may choose to speak instead of sense data and other merely phenomenal entities. When we ask about the reality of things in a scientific sense, we are asking an internal question in the language of things, and such a question will be answered by empirical evidence. When we ask the external question of whether there really is a world of things, we are, Carnap insisted, asking a merely practical question of whether or not to use the forms of expression presented in the thing frame.

Carnap then applies his distinction to systems of a logical rather than empirical nature, that is, frameworks involving terminology for abstract objects such as numbers, propositions, and properties. Consider, for example, the natural number system. In this case, our language will include numerical variables along with their rules for usage. If we were to ask, “Is there a prime number greater than 100?” we should be asking an internal question, the answer to which is to be found not by empirical evidence but by logical analysis based on the rules for new expressions. Since a statement like “5 is a number” is necessarily true, and by existential generalization implies that “There is n such that n is a number,” the existence of numbers is logically necessary within the numerical framework. No one who asks the internal question “Are there numbers?” would seriously consider a negative answer. In contrast, ontologists who ask this question in an external sense are, in Carnap’s view, asking a meaningless question. No one, he claims, has ever succeeded in giving cognitive content to such an external question. The same would be said of questions about propositions and properties: in an external sense, such questions lack cognitive content. For Carnap, the question of realism versus nominalism is, as the Vienna Circle agreed, “a pseudo-question.” [14] Whether one adopts a given linguistic framework is simply a matter of convention.

Virtually no one today would accept the verificationist theory of meaning that motivated Carnap’s claim that external questions lack cognitive content. Conventionalism about abstract objects is not at all an option for the classical theist. For there is no possible world in which uncreated, abstract objects exist, because God exists in all possible worlds and is the Creator of any extra se reality in any world in which he exists. Therefore, it is a metaphysically necessary truth that there are no uncreated abstract objects. Therefore, there is a fact of the matter about whether abstract objects of the sort we are concerned with exist: they do not and cannot exist. Therefore, conventionalism about existence claims regarding abstract objects is necessarily false.

This negative verdict on a conventionalist solution does not imply, however, that Carnap’s analysis is without foundation. Despite the widespread rejection of conventionalism, Carnap’s distinction between external and internal questions continually reappears in contemporary discussions and strikes many philosophers as intuitive and useful. [15] Linnebo puts his finger on Carnap’s fundamental insight when he writes,

In fact, many nominalists endorse truth-value realism, at least about more basic branches of mathematics, such as arithmetic. Nominalists of this sort are committed to the slightly odd view that although the ordinary mathematical statement

-

There are prime numbers between 10 and 20.

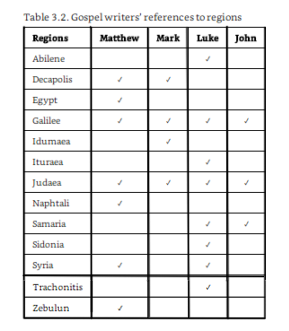

It is true, in fact, that there are no mathematical objects, and in particular there are no numbers. But there is no contradiction here. We must distinguish between the language L M in which mathematicians make their statements and the language LP in which nominalists and other philosophers make theirs. The statement (1) is made in L M . But the nominalist’s claim that (1) is true but that there are no abstract objects is made in LP . The nominalist’s claim is therefore perfectly coherent provided that (1) is translated non-homophonically from L M to LP . And indeed, when the nominalist claims that the truth values of statements in L M are fixed in a way that does not appeal to mathematical objects, it is precisely this kind of non-homophonic translation that she has in mind. [16]

Statements made in LM correspond to Carnap’s internal questions; statements made in LP correspond to external questions. External questions are now to be regarded as meaningful and to have objective answers, but those answers may be quite different from the answers to homophonic questions posed internally. Linnebo unfortunately limits the range of nominalist positions unnecessarily by stipulating that external questions sound different (are not homophonic) compared to the relevant internal questions. Linnebo has in mind Geoffrey Hellman’s translations of mathematical statements into counterfactual conditionals, [17] so that mathematical truths asserted in LP will look or sound quite different from those truths as asserted in LM . That leaves aside nominalisms such as fictionalism, [18] which asserts truth-value realism, but regards statements in LM as fictionally true and homophonic statements in LP as false. If the claim “There are propositions” is stated in L M , then anti-Platonists could accept the claim as stated in L M while denying, in LP , that there are propositions.

Now, since both properties and propositions are abstract objects, the anti-realist will also claim, when not speaking within the linguistic framework that includes talk of properties and propositions, that, from an external point of view, not only are there no propositions, but there are no properties either. Therefore, there really is no such property as truth. This is not as alarming as it may sound. For there is still the truth predicate “is true,” and predications need not be understood as literal ascriptions of properties. The truth predicate is simply a semantic ascent device that allows us to talk about a proposition rather than asserting the proposition itself. For example, instead of saying that God is triune , we can semantically ascend and say that it is true that God is triune . Similarly, whenever the truth predicate is employed, we can semantically descend and simply assert the proposition that is said to be true. For example, instead of saying that it is necessarily true that God exists by himself , we can descend semantically and simply state that, necessarily, God exists by himself . Nothing is gained or lost through such semantic ascent and descent.

Viewing the truth predicate as a semantic ascent device is the key to Arvid Båve’s nominalist deflationary theory of truth, which is a purely semantic theory of truth. [19] The challenge he addresses in formulating a deflationary theory is how to generalize the particular fact that it is true that snow is white iff snow is white . Båve opts for a metalinguistic solution whose basic thesis is

D. Every statement of the form “It is true that p ” is S-equivalent to the corresponding statement ” p “

where any two expressions e and e¢ are S-equivalent iff for any statement context S (), S( e ) and S( e¢ ) are mutually inferable. [20] For example, “It is true that snow is white” entails and is implied by “Snow is white,” so these statements are S-equivalent. Båve’s theory does not require a truth property, but simply lays down a usage rule for the truth predicate. The sole purpose of the truth predicate—says Båve—is the expressive strengthening of language gained by semantic ascent.

Båve emphasizes that (D) satisfies the nominalist constraint

RN. There must be no quantification over, or reference to, propositions and no use of notions defined primarily for propositions.

Because (D) does not quantify or refer to propositions, but simply declares an equivalence between certain forms of statements. [21] On the other hand, (D) does not use, but simply mentions notions related to truth, so it does not conflict with (RN).

Båve’s postulation of the (RN) makes it evident that his theory presupposes something close to the traditional criterion of ontological commitment, which those sympathetic to neutralism, such as myself, reject. [22] A necessity neutralist has no qualms about quantifying or referring to propositions, unless some ontologist stipulates that an existentially charged or metaphysically strong sense is intended. On Båve’s view, despite the fact that propositions do not exist, propositional truth ascriptions can be true because (i) singular terms (such as “that”) need not refer in order for statements featuring them to be true (e.g., statements true about the average American), and (ii) quantification over propositions must be construed substitutively, not objectively. [23] A neutralist perspective renders both of these moves superfluous, since reference and quantification are ontologically neutral.

Why is a semantic ascent device useful or necessary in natural language? Why not simply embrace a Redundancy Theory of truth, which treats the truth predicate as superfluous? The answer is that the truth predicate serves the purpose of blind truth ascriptions. In many cases we find ourselves unable to affirm the proposition or propositions that are said to be true because we are unable to enumerate them due to their sheer number, as in “Everything I told you has come true,” or because we are ignorant of the relevant propositions, as in “Everything stated in the documents is true.” In theory, even blind truth ascriptions are dispensable if we replace them with infinite disjunctions or conjunctions such as “Whether b o q o r o …”. While such infinite disjunctions and conjunctions are unknowable to us, they are known to an omniscient deity, so God has no need of blind truth ascriptions. Therefore, it has no need for a semantic ascent and therefore does not need the truth predicate.

So, in answer to our question, “Propositional Truth—Who Needs It?”, the answer is: certainly not God! In fact, we don’t need propositional truth either. All we need to truly describe the world as it is is the truth predicate, and that won’t saddle us with Platonistic commitments.

Grades:

[1] For an articulation of absolute creationism, a.k.a. theistic activism, see the seminal work by Thomas V. Morris and Christopher Menzel, “Absolute Creation,” American Philosophical Quarterly 23 (1986): 353-362. Morris and Menzel did not clearly differentiate their absolute creationism from a form of non-Platonic realism that we can call divine conceptualism, which replaces concrete mental events in the mind of God with a realm of abstract objects. For a defense of divine conceptualism with respect to propositions and possible worlds, see Greg Welty, “Theistic Conceptual Realism,” in Beyond the Control of God? Six Views on the Problem of God and Abstract Objects, ed. Paul Gould, with articles, responses, and counter-responses by K. Yandell, R. Davis, P. Gould, G. Welty, Wm. L. Craig, S. Shalkowski, and G. Oppy (Bloomsbury, forthcoming). Note well that even the divine conceptualist, although a realist, wants to free his ontology from abstract objects.

[2] For a reference-neutralist account of quantification, see Jody Azzouni, “On ‘On what there is’,” Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 79 (1998): 1–18; idem, Deflating Existential Consequence: A Case for Nominalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). For a reference-neutral account, see Arvid Båve, “A Deflationary Theory of Reference,” Synthèse 169 (2009): 51–73.

[3] The reification of a “that” clause seems to me an excellent example of an empty nominalization. See A. N. Prior, Objects of Thought , ed. P. T. Geach and A. J. P. Kenny (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), pp. 16-30, which rejects “the whole game of ‘nominalizing’ what are not really names of objects at all.” Prior points out that when we say that John fears that such-and-such, we do not mean that John fears a proposition. Rather, expressions like “____ fears that ____” have the function of forming statements out of other expressions, the first of which is a name and the second of which is a statement. They are, as he rightly says, predicates at one end and sentential connectives at the other. So an expression like “It is true that ____” is a sentential connective, not an ascription of property to an object. Mackie notes the similarity of Prior’s solution to substitution quantification; while in Tarski’s scheme “p” is true iff p , the first occurrence of p is in the language of objects and the second in the metalanguage, for Prior in “It is true that p iff p ” both occurrences are in the language of objects (J. L. Mackie, Truth, Probability, and Paradox , Clarendon Library of Logic and Philosophy [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973], pp. 58–61; see William P. Alston, A Realist conception of Truth [Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996], pp. 28–9). For Prior’s view of truth ascriptions to “what is said” see C. J. F. Williams, What is Truth ? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), pp. 32–60.

[4] Jody Azzouni, “Deflationist Truth,” in Handbook on Truth, ed. Michael Glanzberg, (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, forthcoming), sec. VI.

[5] For a particularly clear statement of this assumption, see Michael Devitt, Realism and Truth , 2d ed. (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), p. 28:

Consider a true statement with a very simple structure: the predication ‘ a is F. ‘ This statement is true in virtue of the fact that there exists an object which ‘ a ‘ designates and which is among the objects to which ‘ F ‘ applies. So this statement is true because it has a predicative structure containing words which stand in certain referential relations to parts of reality and because of the way reality is. As long as reality is objective and mind-independent, then the statement is correspondence -true: its truth has all the features we have just abstracted from classical discussions.

Cf. Michael Devitt, Designation (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981), p. 7; Michael Devitt and Kim Stanley, Language and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Language (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1987), pp. 17–18; Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy , s.v. “Reference,” by Michael Devitt. According to Devitt, a statement x has correspondence-truth iff statements of type x are true in virtue of (i) its structure; (ii) the referential relations between its parts and reality; and (iii) the objective, mind-independent nature of that reality. Surprisingly, Devitt seems to think that some statements, e.g. ethical statements, are true even if they do not have correspondence truth (idem, Realism and Truth, 2d ed. [Oxford: Blackwell, 1991], p. 29), which seems to trivialize the question of whether statements with singular terms that lack corresponding real-world objects have correspondence truth.

[6] Searle sees the picture theory as based on a misreading of the correspondence theory of truth, “a classic example of how the surface grammar of words and statements deceives us” (John R. Searle, The Construction of Social Reality [New York: Free Press, 1995], p. 214; see p. 205). John Heil observes that although most analytic philosophers would agree that the picture theory—whose central idea is that the character of reality can be “subtracted” from our (suitably regimented) linguistic representations of reality—is useless, it remains widely influential (John Heil, From an Ontological Point of View [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003]. pp. 5-6). Such thinkers have not digested J. L. Austin’s protest,

The words used to make a true statement need not in any way ‘reflect’, however indirectly, some feature of the situation or event; a statement need no more, in order to be true, reproduce the ‘multiplicity’, for example, or the ‘structure’ or ‘form’ of reality, than a word must be echoic or a writing pictographic. To suppose that it does is to fall back into the error of reading back into the world the features of language (J. L. Austin, ‘Truth’, in Philosophical Papers [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979], p. ***).

See also Heather Dyke, Metaphysics and the Representational Fallacy , Routledge Studies in Contemporary Philosophy (London: Routledge, 2008, p.21).

[7] “A Nominalist Perspective on God and Abstract Objects,” Philosophia Christi 13 (2011): 305-18.

[8] Gottlob Frege held that only in the context of a statement does a word refer to something. But I want to suggest that not even in the context of a (true) statement must a word (or singular term) refer to something, i.e. have a real-world referent. This may not be so different from Frege’s view, if a weak Platonist like Michael Dummett is right. According to Dummett, Frege’s Context Principle required merely that only in the context of a statement do some words become singular terms, so that “the substance of the existential claim eventually seems to dissolve away altogether” (Michael Dummett, “Platonism,” in Truth and Other Enigmas [Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1978], p. 212; cf. idem, “Nominalism,” in Truth and Other Enigmas , pp. 38–41; idem, “Preface,” in Truth and Other Enigmas , pp. xlii–xliv). Dummett is right, I think, that the real problem is the truth of mathematical statements, not those about mathematical terms, not because truth conditions can be given to such statements without the use of such terms, but because the truth of a statement does not require that there be objects corresponding to all the singular terms of a statement. See below, Bob Hale, “Realism and its Oppositions,” in A Companion to the Philosophy of Language , ed. Bob Hale and Crispin Wright, Blackwell Companions to Philosophy 10 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997), pp. 271-308.

[9] Azzouni himself acknowledges that “some philosophers use instances of the T-schema to argue that the truth property is a correspondence property. However, there are many theories about what truth as correspondence amounts to” (Azzouni, “Deflationist Truth”). Some, he notes, interpret the right-hand side of biconditionals to describe a fact or a state of affairs. These theories are at least examples of less robust understandings of correspondence than the word-object interpretation. Later in the same piece, Azzouni muses, “if indeed all true statements share some property, such as a correspondence property… it returns to the kinds of considerations that an earlier tradition in philosophy supposed: the nature of the accounts (if any) of the terms of the statements described as true and false” (ibid., section V). Simon Blackburn and Keith Simmons observe that no one denies the truism that a true proposition corresponds to the facts or tells it like it is; the issue is the kind of fact, a proposition or correspondence (Simon Blackburn and Keith Simmons, “Introduction,” in Truth , ed. Simon Blackburn and Keith Simmons, Oxford Readings in Philosophy [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999], pp. 1, 7). R. C. S. Walker points out that although a correspondence theory can construe truth as a relation between a proposition and something in the world, there is no reason to say anything more than that a proposition is true if things are as it claims to be, which does not commit one even to an ontology of facts. Such an “uninteresting” correspondence theory is quite consistent, he notes, with a redundancy theory of the truth predicate (Ralph C. S. Walker, “Theories of Truth,” in Companion to the Philosophy of Language , pp. 313, 321–3, 328).

[10] See Theodore Sider, Writing the Book of the World (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2011), pp. 170–2. Sider assumes that “fundamental ontological claims are quantifiable.” He acknowledges that this is stipulative. “Ontological realism should not claim that ordinary quantifiers carve at the joints, or that disputes over ordinary quantifiers are substantive. All that matters is that one can introduce a fundamental quantifier, which can then be used to pose substantive ontological questions.” When one does so, one no longer speaks ordinary English, but “a new language—‘Ontologese’—whose quantifiers are stipulated to carve at the joints.” It should be noted that for Sider to understand “there are” to have a fundamental sense does not entail that the objects said to exist are themselves considered fundamental in the sense of irreducibility. It is merely to identify existence claims with quantificational claims. “On my view, accepting an ontology of tables and chairs does not mean that tables and chairs are ‘fundamental entities’, but rather that there are, in the fundamental sense of ‘there are’, tables and chairs.” Such a view would allow non-fundamental entities to actually exist as well.

[11] Rudolf Carnap, “Meaning and Necessity:” A Study in Semantics and Modal Logic (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956), p. 206.

[12] Ibid., pp. 208, 214.

[13] See Scott Soames, “Ontology, Analyticity, and Meaning: the Quine-Carnap Dispute,” in Metametaphysics: New Essays on the Foundations of Ontology , ed. David Chalmers, David Manley, and Ryan Wasserman (Oxford: Clarendon, 2009) , p. 428.

[14] Carnap, “Meaning and Necessity,” p. 215.

[15] See, for example, Thomas Hofweber, “Ontology and Objectivity,” (Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University, 1999), §§1.4-5; 2.3.1; Stephen Yablo, “Does Ontology Rest on a Mistake?” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 72 (1998): 229-61; Arvid Båve, Deflationism: A Use-Theoretic Analysis of the Truth-Predicate , Stockholm Studies in Philosophy 29 (Stockholm: Stockholm University, 2006), pp. 153-4.

[16] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, sv “Platonism in the Philosophy of Mathematics” by Øystein Linnebo, (July 18, 2009), §1.4. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/platonism-mathematics/ .

[17] See Geoffrey Hellman, Mathematics without Numbers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989). For an entertaining account of Hellman’s progress toward his modal structuralism, see idem, “Infinite Possibilities and Possibility of Infinity,” in The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam , ed. R. Auxier (La Salle, Ill.: Open Court, forthcoming), pp. 1–5.

[18] See, for example, Mark Balaguer, Platonism and Anti-Platonism in Mathematics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998); Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy s.v. “Fictionalism in the Philosophy of Mathematics”, by Mark Balaguer, April 22, 2008, http://plato.stanford.edu/entires/fictioanlism-mathematics/ ). Strictly speaking, Balaguer is not a fictionalist, because he thinks that the case for fictionalism and the case for Platonism have comparable weight.

[19] Defended in Båve, Deflationism . Båve has recently addressed a non-nominalist deflationary theory of truth that involves the traditional scheme

(Q) (Pp) (⟨p⟩ is true iff p),

where “P” is a propositional quantifier and instances of ⟨p⟩ are those-clauses that refer to propositions (Arvid Båve, “Formulating Deflationism”, Synthèse [forthcoming]). Since instances of (Q) have singular terms that refer to propositions, Båve takes the theory to commit us to the reality of propositions. But see note 22 below. Båve rejects his earlier metalinguistic theory because (D) does not allow us to infer instances of Tarski’s T-schema for truth (nor was it intended). Whether that is a serious deficiency depends on the desires of a theory of truth. The nominalist is content with a theory for the use of the truth predicate.

[20] Båve, Deflationism, p. 128.

[21] Ibid., pp. 150-2.

[22] It is ironic that Båve himself articulated a Deflationary Theory of Reference that undermines the logic of (NC). See Arvid Båve, “A Deflationary Theory of Reference,” Synthèse 169 (2009): 51–73.

[23] Båve, Deflationism, pp. 158-80.

William Lane Craig is an American Baptist Christian analytic philosopher and theologian. Craig’s philosophical work focuses on the philosophy of religion, metaphysics, and philosophy of time. His theological interests lie in historical Jesus studies and philosophical theology.

Original Blog: http://bit.ly/39xufHz

Translated by Jairo Izquierdo