[Editor’s Note: In part 1 of this series on the evidential value of Paul’s conversion, Dr. Jonathan McLatchie established that (Proposition 1) The accounts in Acts substantially represent Paul’s own conversion testimony, and (Proposition 2) Paul was not plausibly sincerely mistaken. In this second installment, McLatchie tackles the remaining two propositions, showing that Saul’s conversion to Apostle Paul is a remarkably value line of evidence for historic Christianity]

Proposition 3: Paul was not plausibly intentionally deceptive.

Sufferings, Toils, and Hardships: There exists an abundance of evidence that Paul voluntarily endured significant hardships, dangers, persecutions, toils, labors, imprisonments and ultimately execution for the sake of the gospel. This goes a long way towards establishing his sincerity. For example, Clement of Rome, in his sole surviving letter, addressed to the Corinthian church, writes (1 Clement 5) [1],

But not to dwell upon ancient examples, let us come to the most recent spiritual heroes. Let us take the noble examples furnished in our own generation… Owing to envy, Paul also obtained the reward of patient endurance, after being seven times thrown into captivity, compelled to flee, and stoned. After preaching both in the east and west, he gained the illustrious reputation due to his faith, having taught righteousness to the whole world, and come to the extreme limit of the west, and suffered martyrdom under the prefects. Thus was he removed from the world, and went into the holy place, having proved himself a striking example of patience.

This epistle is generally dated to around the year 96 C.E., as the church emerged from the persecution under the emperor Domitian. Clement of Rome had been a companion of Paul, and is likely the individual referred to in Philippians 4:3: “Yes, I ask you also, true companion, help these women, who have labored side by side with me in the gospel together with Clement and the rest of my fellow workers, whose names are in the book of life,” (emphasis added]. Paul’s letter to the Philippians was composed during Paul’s first imprisonment in Rome. The second century church father Irenaeus of Lyons writes the following concerning Clement (Adv. Haer. 3.3.3) [2]:

This man, as he had seen the blessed apostles, and had been conversant with them, might be said to have the preaching of the apostles still echoing [in his ears], and their traditions before his eyes. Nor was he alone [in this], for there were many still remaining who had received instructions from the apostles. In the time of this Clement, no small dissension having occurred among the brethren at Corinth, the Church in Rome dispatched a most powerful letter to the Corinthians, exhorting them to peace, renewing their faith, and declaring the tradition which it had lately received from the apostles.

Clement was thus someone in a position to know about Paul’s sufferings for the sake of the gospel.

Polycarp of Smyrna, in his epistle to the Philippians, also testifies to the persecutions endured by Paul (Poly 9) [3]:

I exhort you all, therefore, to yield obedience to the word of righteousness, and to exercise all patience, such as ye have seen [set] before your eyes, not only in the case of the blessed Ignatius, and Zosimus, and Rufus, but also in others among yourselves, and in Paul himself, and the rest of the apostles. [This do] in the assurance that all these have not run in vain, but in faith and righteousness, and that they are [now] in their due place in the presence of the Lord, with whom also they suffered. For they loved not this present world, but Him who died for us, and for our sakes was raised again by God from the dead.

Irenaeus informs us concerning Polycarp (Adv. Haer. 3.3.4) [4]:

But Polycarp also was not only instructed by apostles, and conversed with many who had seen Christ, but was also, by apostles in Asia, appointed bishop of the Church in Smyrna, whom I also saw in my early youth, for he tarried [on earth] a very long time, and, when a very old man, gloriously and most nobly suffering martyrdom, departed this life, having always taught the things which he had learned from the apostles, and which the Church has handed down, and which alone are true.

Thus, given Polycarp’s acquaintance with the apostles, he was also in a position to know about the sufferings endured by Paul and the other apostles.

In addition to the foregoing, there is a lot of attestation to Paul’s sufferings in Acts and the Pauline corpus. For example, consider Paul’s list of his experiences in 2 Corinthians 11:24-27:

24 Five times I received at the hands of the Jews the forty lashes less one. 25 Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I was stoned. Three times I was shipwrecked; a night and a day I was adrift at sea; 26 on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from robbers, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers; 27 in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, in hunger and thirst, often without food, in cold and exposure.

Paul also expresses in 1 Corinthians 4:9-13:

9 For I think that God has exhibited us apostles as last of all, like men sentenced to death, because we have become a spectacle to the world, to angels, and to men. 10 We are fools for Christ’s sake, but you are wise in Christ. We are weak, but you are strong. You are held in honor, but we in disrepute. 11 To the present hour we hunger and thirst, we are poorly dressed and buffeted and homeless, 12 and we labor, working with our own hands. When reviled, we bless; when persecuted, we endure; 13 when slandered, we entreat. We have become, and are still, like the scum of the world, the refuse of all things.

Paul, moreover, writes to the Thessalonians, “But though we had already suffered and been shamefully treated at Philippi, as you know, we had boldness in our God to declare to you the gospel of God in the midst of much conflict,” (1 Thess 2:2, emphasis added). This raises the question of how the Thessalonians knew about Paul’s shameful treatment in Philippi. When we compare Paul’s letter to the account in Acts, we learn that the shameful treatment to which he was referring is his imprisonment and public beating, uncondemned, despite being a Roman citizen (Acts 16:16-40). We read in Acts 16:35-40:

35 But when it was day, the magistrates sent the police, saying, “Let those men go.” 36 And the jailer reported these words to Paul, saying, “The magistrates have sent to let you go. Therefore come out now and go in peace.” 37 But Paul said to them, “They have beaten us publicly, uncondemned, men who are Roman citizens, and have thrown us into prison; and do they now throw us out secretly? No! Let them come themselves and take us out.” 38 The police reported these words to the magistrates, and they were afraid when they heard that they were Roman citizens. 39 So they came and apologized to them. And they took them out and asked them to leave the city. 40 So they went out of the prison and visited Lydia. And when they had seen the brothers, they encouraged them and departed.

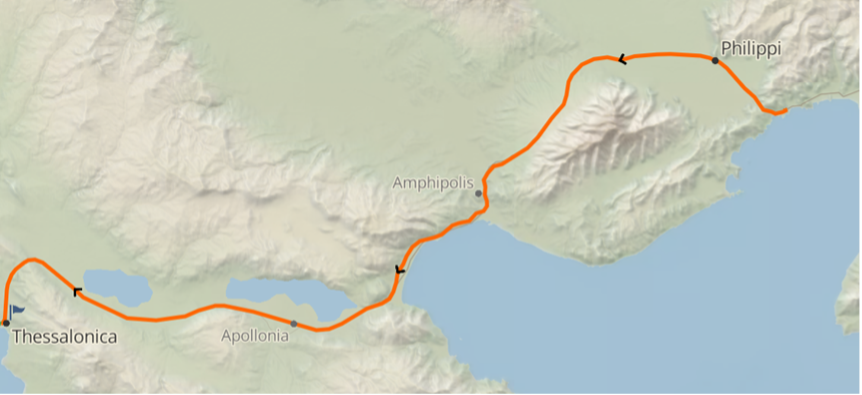

According to Acts 17:1, Paul’s very next port of call, after passing through Amphipolis and Apollonia, was Thessalonica. This was in fact on a major Roman highway (the Via Egnatia) and Amphipolis and Apollonia were overnight stops along that highway. One can envision Paul coming from Philippi to Thessalonica, still full of indignation, and reporting about his shameful treatment to the converts in Thessalonica. This undesigned coincidence between Acts and 1 Thessalonians is all the more striking given that the book of Acts does not appear to be dependent upon 1 Thessalonians, nor vice versa. For example, according to 1 Thessalonians 1:9, Paul writes, “For they themselves report concerning us the kind of reception we had among you, and how you turned to God from idols to serve the living and true God…” Notice the emphasis in this text on the conversion of pagans from idolatry. Acts, on the other hand, emphasizes the conversion of Jews and gentile God-fearers (Acts 17:4). If the author of Acts were using 1 Thessalonians as a source, we might expect emphasis to be placed on the conversion of pagans. The accounts are, of course, not mutually exclusive. In fact, there are allusions in the epistle to concepts that would not make much sense to gentiles who lacked acquaintance with Jewish eschatological thought (1 Thess 4:14-17). Paul also distinguishes believers from gentiles, whose ways they ought not copy (1 Thess 4:4-5). It makes sense, therefore, to understand the “you” that turned to God from idols to be an exaggerated statement — referring to one portion of his audience rather than another. Nonetheless, the surface discrepancy between Acts and 1 Thessalonians points to the independence of these sources.

We also read in Acts 17 about the persecution endured by Paul from a mob of Jews who stirred up trouble for him. According to Acts 17:5-9:

5 But the Jews were jealous, and taking some wicked men of the rabble, they formed a mob, set the city in an uproar, and attacked the house of Jason, seeking to bring them out to the crowd. 6 And when they could not find them, they dragged Jason and some of the brothers before the city authorities, shouting, “These men who have turned the world upside down have come here also, 7 and Jason has received them, and they are all acting against the decrees of Caesar, saying that there is another king, Jesus.” 8 And the people and the city authorities were disturbed when they heard these things. 9 And when they had taken money as security from Jason and the rest, they let them go.

Paul thus had to leave in haste to go to Berea (Acts 17:10). We read in Acts 17:13 that “when the Jews from Thessalonica learned that the word of God was proclaimed by Paul at Berea also, they came there too, agitating and stirring up the crowds.” Paul thus, again, had to leave in haste to travel to Athens — “Then the brothers immediately sent Paul off on his way to the sea, but Silas and Timothy remained there. Those who conducted Paul brought him as far as Athens, and after receiving a command for Silas and Timothy to come to him as soon as possible, they departed.” Acts leaves unexplained why Paul left behind Silas and Timothy. This unexplained allusion is itself a hallmark of verisimilitude in the text. It is the texture of testimony — one does not typically leave loose ends like this in a fictitious work. Moreover, Silas and Timothy are instructed to rejoin Paul “as soon as possible.” Presumably, then, they did rejoin Paul in Athens (though the text does not indicate explicitly). Nonetheless, they are next reported to rejoin Paul not in Athens but in Corinth — and they arrived not from Athens but from Macedonia, where the cities of Thessalonica and Berea are (Acts 18:5). What accounts for this gap in the text? An explanation is provided by 1 Thessalonians 3:1-5:

Therefore when we could bear it no longer, we were willing to be left behind at Athens alone, 2 and we sent Timothy, our brother and God’s coworker in the gospel of Christ, to establish and exhort you in your faith, 3 that no one be moved by these afflictions. For you yourselves know that we are destined for this. 4 For when we were with you, we kept telling you beforehand that we were to suffer affliction, just as it has come to pass, and just as you know. 5 For this reason, when I could bear it no longer, I sent to learn about your faith, for fear that somehow the tempter had tempted you and our labor would be in vain.

Thus, Paul indicates, under the circumstances, he had been concerned for the wellbeing of the Christians in Thessalonica, and so he commissioned Timothy to go back from Athens to Thessalonica to check on the believers there. This explains the gap in the account in Acts, and thereby corroborates the account in Acts. This undesigned coincidence is, again, all the more striking given the independence (as I have shown) between Acts and 1 Thessalonians. Connected to this, there is another undesigned coincidence relating to Paul’s time in Corinth (Acts 18:1-5):

After this Paul left Athens and went to Corinth. 2 And he found a Jew named Aquila, a native of Pontus, recently come from Italy with his wife Priscilla, because Claudius had commanded all the Jews to leave Rome. And he went to see them, 3 and because he was of the same trade he stayed with them and worked, for they were tentmakers by trade. 4 And he reasoned in the synagogue every Sabbath, and tried to persuade Jews and Greeks. 5 When Silas and Timothy arrived from Macedonia, Paul was occupied with the word, testifying to the Jews that the Christ was Jesus.

Paul encounters Aquila and Priscilla in Corinth, who had been exiled from Rome at the instigation of the emperor Claudius. The Roman biographer Suetonius also mentions this episode: “He [Claudius] banished from Rome all the Jews, who were continually making disturbances at the instigation of one Chrestus,” (Life of Claudius 25). Our text in Acts indicates that Paul worked with them as a tentmaker to earn his keep during the week, and that he engaged in his evangelistic work on the Sabbath day, when he went into the synagogue and tried to persuade Jews and Greeks that Jesus is the Christ. However, in response to the arrival of Silas and Timothy from Macedonia, he changed his ministry model such that he devoted himself entirely to the work of the ministry. What prompted this change? Acts does not inform us. However, we read in 2 Corinthians 11:7-9:

7 Or did I commit a sin in humbling myself so that you might be exalted, because I preached God’s gospel to you free of charge? 8 I robbed other churches by accepting support from them in order to serve you. 9 And when I was with you and was in need, I did not burden anyone, for the brothers who came from Macedonia supplied my need. So I refrained and will refrain from burdening you in any way.

Apparently the brothers who came from Macedonia (whom we learn from Acts included Silas and Timothy) brought financial aid to Paul, which enabled him to devote himself entirely to the ministry. This detail, however, is not supplied by Acts. This is further corroborated by Philippians 4:14-16, in which we read (in a letter addressed to one of the churches in Macedonia),

14 Yet it was kind of you to share my trouble. 15 And you Philippians yourselves know that in the beginning of the gospel, when I left Macedonia, no church entered into partnership with me in giving and receiving, except you only. 16 Even in Thessalonica you sent me help for my needs once and again.

This, once again, serves to confirm the account in Acts — which reveals that Paul was willing to work for his keep as a tentmaker. In other words, he was evidently not in ministry for the purpose of extorting people for money. Moreover, the account in Acts continues with a note about another episode of opposition against Paul: “And when they opposed and reviled him, he shook out his garments and said to them, ‘Your blood be on your own heads! I am innocent. From now on I will go to the Gentiles,’” (Acts 18:6). This coincidence is all the more striking given the independence of Acts and 2 Corinthians, as demonstrated earlier in this article.

Another undesigned coincidence bearing on Paul’s sufferings relates to Paul’s statement in 2 Timothy 3:10-11:

10 You, however, have followed my teaching, my conduct, my aim in life, my faith, my patience, my love, my steadfastness, 11 my persecutions and sufferings that happened to me at Antioch, at Iconium, and at Lystra—which persecutions I endured; yet from them all the Lord rescued me.

The sufferings mentioned here are described in Acts 13:50-51 and 14:1-7, 19-21. Paul seems to imply, in his letter to Timothy, that Timothy had in fact witnessed the persecutions that he had endured in those cities. According to Acts, Paul embarked on a second missionary journey through the same country as the first journey. The purpose of his second missionary trip is given in Acts 15:36: “Let us return and visit the brothers in every city where we proclaimed the word of the Lord, and see how they are.” Thus, we learn, that the purpose of the journey was to check on those who had been converted during the first journey, to see how they were doing. In Acts 16:1-2, we further learn, “Paul came also to Derbe and to Lystra. A disciple was there, named Timothy, the son of a Jewish woman who was a believer, but his father was a Greek. 2 He was well spoken of by the brothers at Lystra and Iconium.” We are thereby informed that Timothy’s hometown was either Derbe or Lystra. And it is apparent from the text that Timothy had already been converted by this time. Paul himself refers to Timothy as “my true child in the faith” (1 Tim 1:2) and “my beloved child” (2 Tim 1:2). This implies that Timothy was probably Paul’s own convert. It then follows that Timothy was very likely converted during Paul’s preceding missionary journey through these cities, at the very time when Paul had undergone the persecutions referred to in the epistle. This supports both the historicity of Acts, as well as the genuineness of the pastoral epistles (which are among the disputed Pauline letters). For a more detailed discussion of the authenticity of the pastoral epistles, see my essay here.

There is also external evidence that corroborates the accounts in Acts concerning Paul’s suffering for the gospel. For example, Acts 22:25-29 describes Paul being before the Roman tribune:

25 But when they had stretched him out for the whips, Paul said to the centurion who was standing by, “Is it lawful for you to flog a man who is a Roman citizen and uncondemned?” 26 When the centurion heard this, he went to the tribune and said to him, “What are you about to do? For this man is a Roman citizen.” 27 So the tribune came and said to him, “Tell me, are you a Roman citizen?” And he said, “Yes.” 28 The tribune answered, “I bought this citizenship for a large sum.” Paul said, “But I am a citizen by birth.” 29 So those who were about to examine him withdrew from him immediately, and the tribune also was afraid, for he realized that Paul was a Roman citizen and that he had bound him. [emphasis added]

Note the tribune’s words to Paul, “I bought this citizenship for a large sum.” What is the historical background here? The second century Roman historian Cassius Dio informs us that, during the reign of Claudius it was introduced that one could purchase a Roman citizenship for a great sum. He writes (Historiae Romanae 60.17),

For inasmuch as Romans had the advantage over foreigners in practically all respects, many sought the franchise by personal application to the emperor, and many bought it from Messalina and the imperial freedmen. For this reason, though the privilege was at first sold only for large sums, it later became so cheapened by the facility with which it could be obtained that it came to be a common saying, that a man could become a citizen by giving the right person some bits of broken glass.

Thus, though the privilege of Roman citizenship sold at first for great sums of money, the price progressively came down, until it had become so cheapened that it came to be a common saying that one could become a Roman citizen by bringing the right person some pieces of broken glass. This adds color to the tribune’s words, “I bought this citizenship for a large sum,” insinuating that Paul was able to acquire his citizenship for much less. Paul, in turn, corrects the tribune that he was a citizen by birth. Acts does not explain, for the sake of his readers, this historical background. Cassius Dio, in providing this background, renders the narrative in Acts quite credible.

There is also a wealth of evidence for the authenticity of Paul’s voyage, as a prisoner bound for Rome, that ended in shipwreck (Acts 27). The report of that voyage notes, in verses 3-6, that,

3 The next day we put in at Sidon. And Julius treated Paul kindly and gave him leave to go to his friends and be cared for. 4 And putting out to sea from there we sailed under the lee of Cyprus, because the winds were against us. 5 And when we had sailed across the open sea along the coast of Cilicia and Pamphylia, we came to Myra in Lycia. 6 There the centurion found a ship of Alexandria sailing for Italy and put us on board.

Colin Hemer comments, “Myra, like Patara again, was a principal port for the Alexandrian corn-ships, and precisely the place where Julius would expect to find a ship sailing to Italy in the imperial service. Its official standing here is further illustrated by the Hadrianic granary. Myra was also the first of these ports to be reached by a ship arriving from the east, as Patara had been previously from the reverse direction.”[5] [13]

Verses 13-14 indicate that they “…sailed along Crete, close to the shore. But soon a tempestuous wind, called the northeaster, struck down from the land.” In confirmation of Luke’s report, there is indeed a well confirmed wind that rides over Crete from the Northeast, and which is strongest at this exact time near the Day of Atonement in the Fall (Acts 27:9). Acts 27:16 describes how the ship was blown off course towards a small island called Cauda. What is impressive is that the island of Cauda is more than 20 miles west-southwest of where the storm likely struck the travelers in the Bay of Messara. This is precisely where the trajectory of a north-easterly wind should have carried them, and it is not the sort of information someone would have inferred without having been blown there. Ancients found it nearly impossible to properly locate islands this far out. Colin Hemer notes that[6],

As the implications of such details are further explored, it becomes increasingly difficult to believe that they could have been derived from any contemporary reference work. In the places where we can compare, Luke fares much better than the encyclopaedist Pliny, who might be regarded as the foremost first-century example of such a source. Pliny places Cauda (Gaudos) opposite Hierapytna, some ninety miles too far east (NH 4.12.61). Even Ptolemy, who offers a reckoning of latitude and longitude, makes a serious dislocation to the northwest, putting Cauda too near the western end of Crete, in a position which would not suit the unstudied narrative of our text (Ptol. Geog. 3.15.8).

There are many other points at which Paul’s voyage and shipwreck may be confirmed. For a much more detailed discussion, I refer readers to James Smith’s book, The Voyage and Shipwreck of St. Paul. [7]

Paul rejoiced in his own sufferings for the name of Christ. He wrote to the Philippians, “Even if I am to be poured out as a drink offering upon the sacrificial offering of your faith, I am glad and rejoice with you all. Likewise you also should be glad and rejoice with me,” (Phil 2:17-18).

An additional point that bears mentioning is that Paul not only willingly endured hardships and persecutions himself, but he expected other believers to do the same. Consider the following texts:

- Philippians 1:29-30: For it has been granted to you that for the sake of Christ you should not only believe in him but also suffer for his sake, engaged in the same conflict that you saw I had and now hear that I still have.

- 1 Thessalonians 1:4-5: For when we were with you, we kept telling you beforehand that we were to suffer affliction, just as it has come to pass, and just as you know. For this reason, when I could bear it no longer, I sent to learn about your faith, for fear that somehow the tempter had tempted you and our labor would be in vain. This is evidence of the righteous judgment of God, that you may be considered worthy of the kingdom of God, for which you are also suffering.

- 2 Thessalonians 1:4: Therefore we ourselves boast about you in the churches of God for your steadfastness and faith in all your persecutions and in the afflictions that you are enduring.

- Romans 3:3-4: Not only that, but we rejoice in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope.

- Romans 8:35-36: Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or danger, or sword? As it is written, “For your sake we are being killed all the day long; we are regarded as sheep to be slaughtered.”

- 2 Corinthians 6:4-10: but as servants of God we commend ourselves in every way: by great endurance, in afflictions, hardships, calamities, beatings, imprisonments, riots, labors, sleepless nights, hunger; by purity, knowledge, patience, kindness, the Holy Spirit, genuine love; by truthful speech, and the power of God; with the weapons of righteousness for the right hand and for the left; through honor and dishonor, through slander and praise. We are treated as impostors, and yet are true; as unknown, and yet well known; as dying, and behold, we live; as punished, and yet not killed; as sorrowful, yet always rejoicing; as poor, yet making many rich; as having nothing, yet possessing everything.

Sir George Lyttelton notes [8],

But at that time when St. Paul undertook the preaching of the Gospel to persuade any man to be a Christian, was to persuade him to expose himself to all the calumnies human nature could suffer. This St Paul knew; this he not only expected, but warned those he taught to look for it too… How much reason he had to say this, the hatred, the contempt, the torments, the deaths endured by the Christians in that age, and long afterwards, abundantly prove. Whoever professed the Gospel under these circumstances, without an entire conviction of its being a Divine revelation, must have been mad; and if he made others profess it by fraud or deceit, he must have been worse than mad; he must have been the most hardened wretch that ever breathed. Could any man who had in his nature the least spark of humanity, subject his fellow-creatures to so many miseries; or could one that had in his mind the least ray of reason, expose himself to share them with those he deceived, in order to advance a religion which he knew to be false, merely for the sake of its moral doctrines? Such an extravagance is too absurd to be supposed; and I dwell too long on a notion that upon a little reflection confutes itself.

Short of being, as Lyttelton put it, the most hardened wretch that ever breathed, how could Paul expect his fellow believers to voluntarily undertake tremendous hardships and sufferings, even martyrdom, unless he had a sincere conviction of the gospel’s truth?

Was Paul in it for the Money? In view of the voluntary sufferings of Paul, evinced above, it appears to be highly improbable that he was engaging in deliberate deception. And what motive could he have for had such a deception? Paul does not appear to have been in it for the money, as already seen from the reference to 1 Corinthians 4:11-13, and the foregoing discussion of Paul’s time in Corinth in Acts 18. We also read in 1 Corinthians 9:14-18:

14 In the same way, the Lord commanded that those who proclaim the gospel should get their living by the gospel. 15 But I have made no use of any of these rights, nor am I writing these things to secure any such provision. For I would rather die than have anyone deprive me of my ground for boasting. … 18 What then is my reward? That in my preaching I may present the gospel free of charge, so as not to make full use of my right in the gospel.

Similarly, Paul writes in 2 Corinthians 12:14: “Here for the third time I am ready to come to you. And I will not be a burden, for I seek not what is yours but you. For children are not obligated to save up for their parents, but parents for their children.”

Paul also appeals to the Thessalonians’ memory of how Paul was among them: “For you yourselves know how you ought to imitate us, because we were not idle when we were with you, nor did we eat anyone’s bread without paying for it, but with toil and labor we worked night and day, that we might not be a burden to any of you,” (2 Thess 3:7-8).

In Paul’s address before the Ephesian elders, Paul likewise states, “I coveted no one’s silver or gold or apparel. You yourselves know that these hands ministered to my necessities and to those who were with me. In all things I have shown you that by working hard in this way we must help the weak and remember the words of the Lord Jesus, how he himself said, ‘It is more blessed to give than to receive,’” (Acts 20:33-35). The unity in style and mannerism between the account of Paul’s address to the Ephesian elders in Acts 20:17-38 and Paul’s letters supports the substantial authenticity of this speech (particularly given the demonstrable independence between Acts and the Pauline corpus). Lydia McGrew comments [9].

The speech breathes the personality of the author of the epistles, including both his genuine love and warm-heartedness and what one might less charitably be inclined to call his emotional manipulativeness and self-dramatization. The same Paul who brings the elders of Miletus to tears with his references to his own trials and tears (Acts 20:19) and his prediction of never seeing them again (Acts 20:25, 36-38) is the Paul who attempts, probably successfully, to induce Philemon to free the slave Onesimus by telling him that he ‘owes him his own life’ (Philem vss 17-19). He is the same Paul who says so much about his own trials and distresses in 1 Corinthians and reminds his readers that he is their spiritual father (1 Cor 4:8-14). The same Paul who launches, at this intimate moment of farewell to his dear friends, into a spirited defense of his own blamelessness in financial matters (Acts 20:33-35) is the Paul who harps on this theme repeatedly in the epistles and who is almost painfully defensive about his apostleship in 2 Corinthians 11-12. The same Paul who urges the Corinthians to be imitators of himself (1 Cor 4:16), who says that the “care of all the churches comes upon him daily (2 Cor 11:28), and who earnestly uses his apostolic authority, his love, and the sheer force of his personality to dissuade the Galatians from yielding to the demand of circumcision (Gal 4:16-20) is the Apostle Paul who tells the elders in Acts 20:29-32 that after his departure they will be assailed by false teachers and should resist, remembering how he himself ‘admonished them with tears’ during his ministry.

We also see evidence of Paul’s integrity in regards to finances in Acts 20:1-4:

After the uproar ceased, Paul sent for the disciples, and after encouraging them, he said farewell and departed for Macedonia. 2 When he had gone through those regions and had given them much encouragement, he came to Greece. 3 There he spent three months, and when a plot was made against him by the Jews as he was about to set sail for Syria, he decided to return through Macedonia. 4 Sopater the Berean, son of Pyrrhus, accompanied him; and of the Thessalonians, Aristarchus and Secundus; and Gaius of Derbe, and Timothy; and the Asians, Tychicus and Trophimus.

This text provides the longest list in the book of Acts of companions of Paul all travelling somewhere at the same time. Moreover, their respective locations are very carefully noted together with their names. Timothy is related to Lystra and Derbe, even though this information was already supplied in Acts 16:1, and there is no apparent reason why this should be repeated here. It is, however, quite plausible that these various individuals are intended as representatives of the various gentile churches who were contributing to the collection that Paul was gathering at this time for the relief of the saints in Jerusalem. We see throughout Paul’s letters that he desires that everyone know that he is blameless about money and has no agenda of extorting people. This is a major theme in the Corinthian epistles in particular. In 1 Corinthians 16:3-4, Paul writes concerning the gathered collection, “And when I arrive, I will send those whom you accredit by letter to carry your gift to Jerusalem. If it seems advisable that I should go also, they will accompany me.” In other words, Paul suggests that someone else, rather than himself, accompany the Corinthians’ contribution to Jerusalem — he will go only if it seems appropriate. It seems likely, therefore, that Paul was accompanied from Greece to Jerusalem by this large group to demonstrate that he had not absconded with any of the collection and to provide more security as he made the journey. Acts never mentions the collection at all, except in Paul’s cryptic allusion to bringing alms to his nation in his speech before Felix in Acts 24:17.

Was Paul in it for the Power? It does not appear that Paul was in pursuit of power either. In 1 Corinthians 15:9, he describes himself as “the least of the apostles.” There is no indication that he felt himself in competition for power with the other apostles. This is further expressed in 1 Corinthians 3:4-9:

4 For when one says, “I follow Paul,” and another, “I follow Apollos,” are you not being merely human? 5 What then is Apollos? What is Paul? Servants through whom you believed, as the Lord assigned to each. 6 I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth. 7 So neither he who plants nor he who waters is anything, but only God who gives the growth. 8 He who plants and he who waters are one, and each will receive his wages according to his labor. 9 For we are God’s fellow workers. You are God’s field, God’s building.

In fact, Paul went up to Jerusalem to those who had been apostles before him to confirm that the gospel he had been proclaiming to the gentiles was the same as theirs, “in order,” he writes, “to make sure I was not running or had not run in vain,” (Gal 2:2).

Even when Paul was in prison in Rome, and others were seeking to take advantage of Paul’s circumstances for their own gain, Paul wrote to the Philippians (1:15-18),

15 Some indeed preach Christ from envy and rivalry, but others from good will. 16 The latter do it out of love, knowing that I am put here for the defense of the gospel. 17 The former proclaim Christ out of selfish ambition, not sincerely but thinking to afflict me in my imprisonment. 18 What then? Only that in every way, whether in pretense or in truth, Christ is proclaimed, and in that I rejoice.

Paul cared more about the advance of the gospel than his own reputation or influence.

Paul wrote to the Thessalonian Christians and appealed to their own experience of his conduct among them (1 Thess 2:3-12):

3 For our appeal does not spring from error or impurity or any attempt to deceive, 4 but just as we have been approved by God to be entrusted with the gospel, so we speak, not to please man, but to please God who tests our hearts. 5 For we never came with words of flattery, as you know, nor with a pretext for greed—God is witness. 6 Nor did we seek glory from people, whether from you or from others, though we could have made demands as apostles of Christ. 7 But we were gentle among you, like a nursing mother taking care of her own children. 8 So, being affectionately desirous of you, we were ready to share with you not only the gospel of God but also our own selves, because you had become very dear to us. 9 For you remember, brothers, our labor and toil: we worked night and day, that we might not be a burden to any of you, while we proclaimed to you the gospel of God. 10 You are witnesses, and God also, how holy and righteous and blameless was our conduct toward you believers. 11 For you know how, like a father with his children, 12 we exhorted each one of you and encouraged you and charged you to walk in a manner worthy of God, who calls you into his own kingdom and glory.

Another text that argues against Paul’s motivation being power is Acts 14:11-15, in which we read about an episode that transpired while Paul and Barnabas were at Lystra:

11 And when the crowds saw what Paul had done, they lifted up their voices, saying in Lycaonian, “The gods have come down to us in the likeness of men!” 12 Barnabas they called Zeus, and Paul, Hermes, because he was the chief speaker. 13 And the priest of Zeus, whose temple was at the entrance to the city, brought oxen and garlands to the gates and wanted to offer sacrifice with the crowds. 14 But when the apostles Barnabas and Paul heard of it, they tore their garments and rushed out into the crowd, crying out, 15 “Men, why are you doing these things? We also are men, of like nature with you, and we bring you good news, that you should turn from these vain things to a living God, who made the heaven and the earth and the sea and all that is in them.

This text is historically credible. First, note that the crowds are said to have spoken in Lycaonian. Jefferson White explains,

“Concerning the crowd’s Lycaonian dialect, historical evidence reveals that the lower classes of the interior of Asia Minor still spoke in their native tongues as late as the first century. This was in contrast to the more heavily populated areas along the Mediterranean coast, where native languages had largely disappeared in favor of Greek. Thus Luke’s reference to a native dialect in this inland city is accurate.” [10]

Archaeological evidence also indicates that Zeus and Hermes were the local cult deities of Lystra — various inscriptions reveal dedications to these two deities, which were linked in common worship. Evidence also indicates that it was commonly thought in the ancient world that, when there was a visitation of two deities, the lesser deity was the spokesman — this explains why Barnabas was called Zeus, even though Zeus was the more prominent of the two deities.

Take note of Paul’s and Barnabas’ reaction to their being hailed as deities — this is not the reaction of a narcissist who is hell-bent on his pursuit of power.

For the reasons surveyed above, I think it can be safely said that Paul was sincere in his belief that he had had an encounter with the risen Jesus on the road to Damascus — he was not setting out to intentionally deceive people. As Sir George Lyttelton concludes [11],

St. Paul could have no rational motive to become a Disciple of Christ, unless he sincerely believed in him, this observation: that whereas it may be objected to the other Apostles, by those who are resolved not to credit their testimony, that having been deeply engaged with Jesus during his life, they were obliged to continue the same professions after his death, for the support of their own credit, and from having gone too far to go back, this can by no means be said of St Paul. On the contrary, whatever force there may be in that way of reasoning, it all tends to convince us that St Paul must naturally have continued a Jew, and an enemy of Christ Jesus: if they were engaged on one side, he was as strongly engaged on the other. If shame withheld them from changing sides, much more ought it to have stopped him, who, being of a higher education and rank in life a great deal than they, had more credit to lose, and must be supposed to have been vastly more sensible to that sort of shame. The only difference was, that they, by quitting their Master after his death, might have preserved themselves; whereas he, by quitting the Jews, and taking up the cross of Christ, certainly brought on his own destruction.

Conclusion

I began this essay by making the case that the accounts in Acts 9, 22, and 26 substantially represent the claimed testimony of the apostle Paul himself. I then proceeded to show that, given this premise, it is incredibly implausible either that Paul was sincerely mistaken in his belief that he had encountered the risen Christ or that he gave false testimony with an intent to deceive. The best explanation of the evidence, therefore, is that Paul did indeed encounter Christ on the Damascus road, and was appointed to the office of apostle by Christ himself. Since Jesus identified as the one whom Paul was persecuting (Acts 9:5, 22:8, 26:15), it stands as an endorsement of the core beliefs of the group that Paul was persecuting — chief among which was the belief that Jesus had been physically raised from the dead. The evidence surveyed in the foregoing, therefore, provides an independent line of confirmation of the resurrection of Jesus.

I will conclude this essay with a final quote from Sir George Lyttelton, who wrote the following at the conclusion of his book on Paul’s conversion [12]:

Some difficulties occur in that Revelation, which human reason can hardly clear; but as the truth of it stands upon evidence so strong and convincing, that it cannot be denied without much greater difficulties than those that attend the belief of it, as I have before endeavored to prove, we ought not to reject it upon such objections, however mortifying they may be to our pride. That indeed would have all things made plain to us; but God has thought proper to proportion our knowledge to our wants, not our pride. All that concerns our duty is clear; and as to other points either of natural or revealed religion, if he has left some obscurities in them, is that any reasonable cause of complaint? Not to rejoice in the benefit of what he has allowed us to know, from a presumptuous disgust at our incapacity of knowing more, is as absurd as it would be to refuse to walk, because we cannot fly.

References:

[1] Clement of Rome, “The First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians,” in The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, vol. 1, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 6.

[2] Irenaeus of Lyons, “Irenæus against Heresies,” in The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, vol. 1, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 416.

[3] Polycarp of Smryna, “The Epistle of Polycarp to the Philippians,” in The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, vol. 1, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 35.

[4] Irenaeus of Lyons, “Irenæus against Heresies,” in The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, vol. 1, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 416.

[5] Colin J. Hemer, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History, ed. Conrad H. Gempf (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1990), 134.

[6] Ibid., 331.

[7] James Smith, The Voyage and Shipwreck of St. Paul: With Dissertations on the Life and Writings of St. Luke, and the Ships and Navigation of the Ancients, ed. Walter E. Smith, Fourth Edition, Revised and Corrected. (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1880).

[8] George Lyttelton, Observations on the Conversion and Apostleship of St. Paul (The Institute Trust, 1747), 36-39.

[9] Lydia McGrew, Hidden in Plain View: Undesigned Coincidences in the Gospels and Acts (Tampa, FL: DeWard Publishing Company, 2017), 157.

[10] Jefferson White, Evidence and Paul’s Journeys: An Historical Investigation into the Travels of the Apostle Paul (Independently Published, 2001/2019), 14.

[11] Lyttelton 1747, 39-40.

[12] Ibid., 119-120.

Recommended Resources:

Why We Know the New Testament Writers Told the Truth by Frank Turek (mp4 Download)

The Top Ten Reasons We Know the NT Writers Told the Truth mp3 by Frank Turek

The New Testament: Too Embarrassing to Be False by Frank Turek (DVD, Mp3, and Mp4)

Oh, Why Didn’t I Say That? Is the Bible Historically Reliable? by Dr. Frank Turek DVD, Mp4, Mp3 Download.

Dr. Jonathan McLatchie is a Christian writer, international speaker, and debater. He holds a Bachelor’s degree (with Honors) in forensic biology, a Masters’s (M.Res) degree in evolutionary biology, a second Master’s degree in medical and molecular bioscience, and a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology. Currently, he is an assistant professor of biology at Sattler College in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. McLatchie is a contributor to various apologetics websites and is the founder of the Apologetics Academy (Apologetics-Academy.org), a ministry that seeks to equip and train Christians to persuasively defend the faith through regular online webinars, as well as assist Christians who are wrestling with doubts. Dr. McLatchie has participated in more than thirty moderated debates around the world with representatives of atheism, Islam, and other alternative worldview perspectives. He has spoken internationally in Europe, North America, and South Africa promoting an intelligent, reflective, and evidence-based Christian faith.

Originally posted at: https://bit.ly/3DEJ7rr

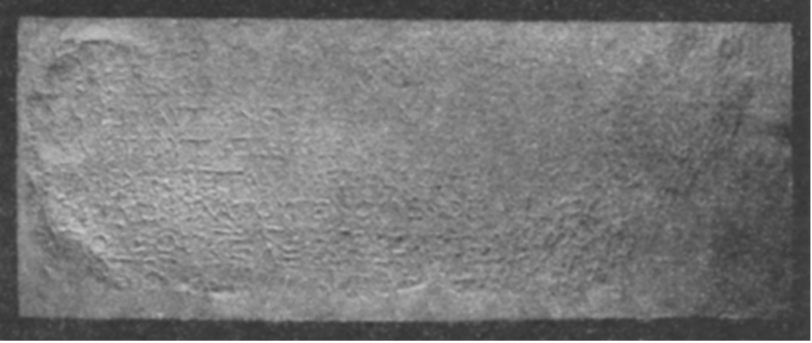

Though we cannot say for certain, it is quite plausible that this is the same individual spoken of in Acts. Though the precise date of the inscription is uncertain, it likely belongs to the first century C.E. This individual is said to have served as Proconsul during the tenth year of an emperor, though the name is missing from the inscription. Ben Witherington notes, “If the emperor in question was Claudius, the inscription would date to about A.D. 50, but the very date line seems to be a later addition. It thus remains possible that this refers to the same Sergius Paulus as mentioned in Acts, but it is also possible on epigraphical grounds that the inscription comes from as late as the time of Hadrian in the second century.”

Though we cannot say for certain, it is quite plausible that this is the same individual spoken of in Acts. Though the precise date of the inscription is uncertain, it likely belongs to the first century C.E. This individual is said to have served as Proconsul during the tenth year of an emperor, though the name is missing from the inscription. Ben Witherington notes, “If the emperor in question was Claudius, the inscription would date to about A.D. 50, but the very date line seems to be a later addition. It thus remains possible that this refers to the same Sergius Paulus as mentioned in Acts, but it is also possible on epigraphical grounds that the inscription comes from as late as the time of Hadrian in the second century.”