By Brian Huffling

Many people don’t know how to study the Bible, or even where to begin. The Bible is a long collection of books that contains much about ancient history, difficult concepts, and is very intimidating for people who want to read it but don’t know where to start. This article will describe some of the principles of interpreting the Bible (hermeneutics) that are taught in basic Bible college and seminary classes (but are easy enough for anyone to understand). This is not a 12-step method to anything, it is simply a sound method to examine the biblical text. Well, it is a 3-step method: observation, interpretation, and application.

OBSERVATION

When we read a passage, we typically want to ask, “What does it mean?” But there is a more basic question we should ask first: “What does it say?” It is easy to read into the text something that is not there (this is called eisegesis), often because we simply put words there that aren’t but think they should be. For example, John 20:19 says: “On the evening of that day, the first day of the week, the doors being locked where the disciples were for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood among them and said to them, ‘Peace be with you.’” It is often stated that Jesus walked through a wall or the door. However, the text doesn’t say that. It simply says the doors were locked and Jesus appeared to them. Maybe he walked through the door or wall, or maybe he just showed up. We have to observe the text carefully. There are various aspects of the text to observe.

One major area to observe is genre. For example, narrative is treated differently than poetry or didactic literature (such as the epistles). Narrative simply describes what happened, whereas didactic literature prescribes what should happen (in other words, it gives commands). Of course there can be narrative in epistolary literature (or vice versa), but the point is that one needs to be careful, for example, not to make an imperative out of a simple description. It is also arguably the case that one should not use parables to base his theology. This is debated, but the point is that we should be aware of the type of genre we are reading when doing interpretation.

Another aspect of the text to observe is the historical and cultural context. For example, Revelation 3:15-16 says, “I know your works: you are neither cold nor hot. Would that you were either cold or hot! So, because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of my mouth.” People often say that Jesus would rather you be completely dedicated to him or not dedicated at all. (Does the latter even make sense?) Actually, what we know from historical information is that the the area being referred to (Laodicea) had hot water pumped in from hot springs and cold water pumped in from cold springs. People went to the hot springs for healing (like being in a hot tub) and went to the cold springs for refreshment (something I would never do as I hate cold water), so the Laodiceans tried to get that water for themselves. However, by the time the water got to Laodicea, it was lukewarm and nasty and when people drank it it would make them vomit. Jesus is saying that he wanted the Laodiceans to be spiritually healing or refreshing. Rather, what the church there had to offer was spiritually nasty. Historical knowledge here clarifies the text for us.

It is also imperative to observe the textual and literary context, that is, what comes before and after the passage you are looking at. We get into trouble when we start looking at passages without understanding the context in which they are in. Sometimes we don’t have to go back to the beginning of the book, but we should at least start with he literary unit in which our passage is found. The chapters and verses don’t necessarily determine that, so pay attention to what the text is saying. Does the passage start with a conjunction such as “but” or “and?” Then it’s a good idea to see what preceded that conjunction.

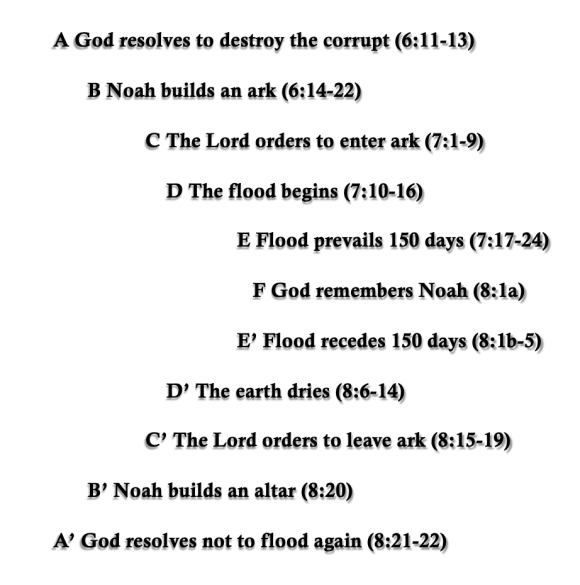

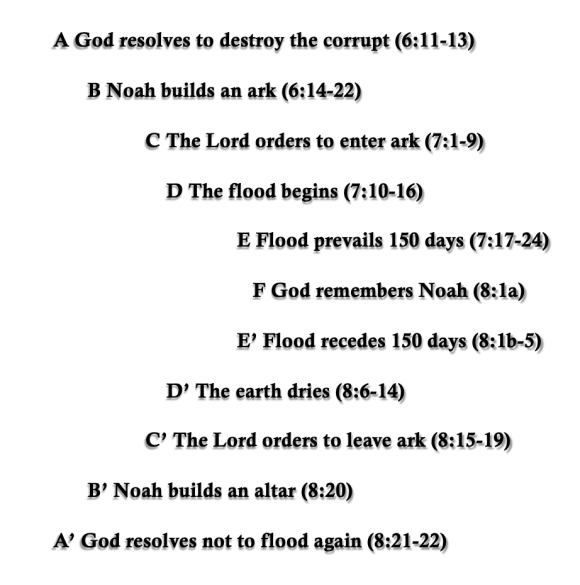

In looking at the textual and literary context we can observe the structure of the passage. Are words, phrases or sentences in a certain order or pattern? For example, we should be on the look out for chiasms. Chiasms are structures that have an ABCBA order. Sometimes it could have an ABBA order, such as in Romans 10:9-10, which says: “because, if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved. For with the heart one believes and is justified, and with the mouth one confesses and is saved.” Notice the mouth/heart/heart/mouth structure. The middle part of the chiasm is meant to emphasize the author’s point. Look at the below chiasm from the flood story:

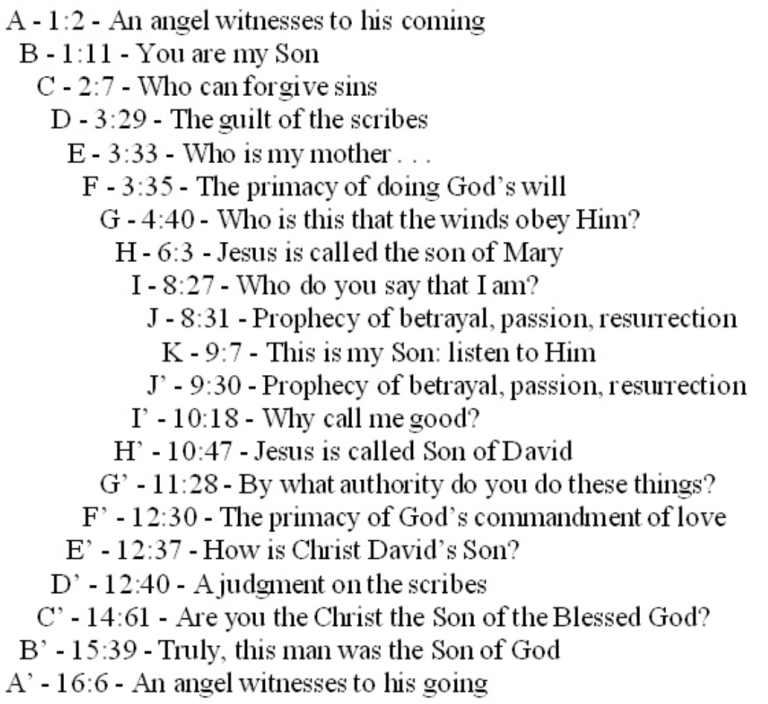

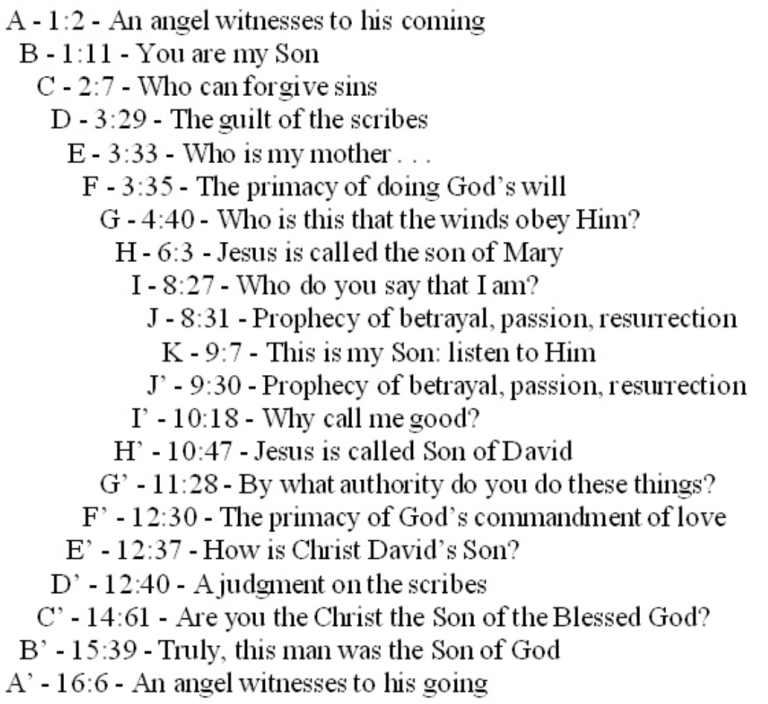

Such a long chiasm is hard to identify, but if we start to see patterns in the wording of the text and in a certain order, it can be found. While the story of the flood is typically thought to be about judgment, the focal point of the flood story is actually that God remembered Noah. The entire Book of Mark is actually a chiasm. The below image is taken from my Hermeneutics class notes by Dr. Tom Howe:

Another area to observe is terms. This particular area of observation is difficult not to blend with interpreting (asking about the meaning). However, we have to observe what terms are (and are not) used. As you probably know, the Bible was not written in English. Almost all of the Old Testament was written in Hebrew, with some areas being written in Aramaic (such as much of Daniel with the rest being Hebrew—something that itself needs to be observed), and the New Testament was written in Greek. Word studies are very popular, and many times all of Bible study is simply reduced to a word study, which it should not be. But it should be part of our study. It is important to know what underlying original word was used, if we can, when doing a Bible study. Some people are more trained at this than others, but it is a goal we should have.

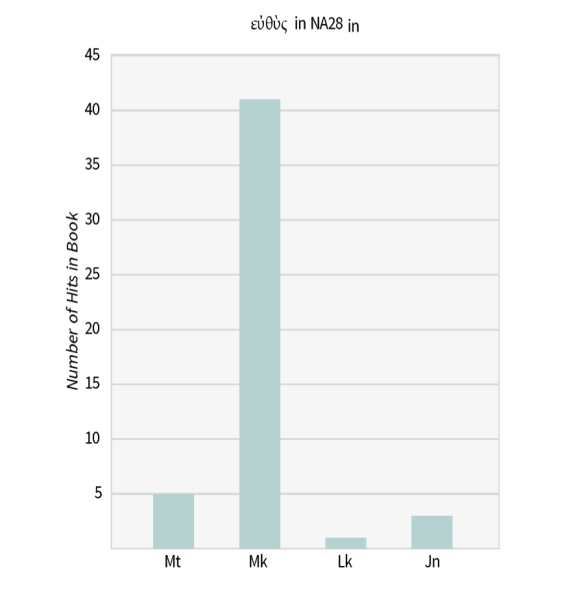

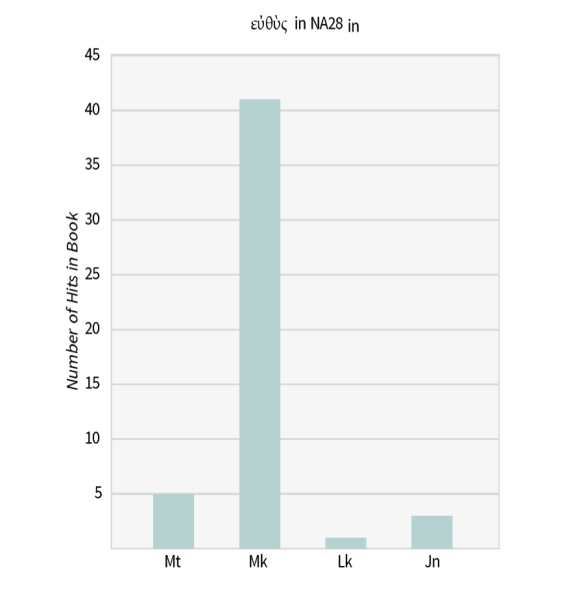

When observing terms, we need to look for terms that are repeated. Such repetition of terms can show the structure of the book or passage. Such as the word “immediately” in Mark. The word “immediately” is used 5 times in Matthew, and fewer than that in Luke and John. But Mark uses it over 40 times. Why is that? It is obviously an important term for him. Let me put that into a graphic for you:

We should also observe terms that are difficult to understand, such as “predestination.” Figure of speech is also important to observe. Sometimes it is debatable as to whether a text is a figure of speech or not. There are some rules that can help discover if something should be taken as a figure of speech. For example, if something for whatever reason cannot be taken literally, then it should be taken as a figure of speech—such as when Jesus told his disciples at the Last Supper that the bread and wine was his body and blood. If something would be an immoral command from God, such as when Jesus said to eat and drink his body, that should be taken as a figure of speech. Of course, these examples are debatable between Catholics and Protestants, but the general rule holds true that when something cannot be taken literally, it needs to be taken as a figure of speech.

We also need to take note of words that are unfamiliar to us, such as “talent.” When we read, for example, in the parable of the unforgiving servant, that the servant owed ten thousand talents, we need to know what a talent is. (This gets blurry with our second step, interpretation.) Some translations, such as the NIV, translate “ten thousand talents” here as “ten thousand bags of gold.” One talent was about twenty years worth of wages. More on this in the next section, but the point is we need to be aware of these words—in other words, observe them.

INTERPRETATION

This is the step we generally start with but shouldn’t: what does the text mean? Back to the “talent” story. We observed that the word used in the parable of the unforgiving servant is “talent,” but the NIV says “bags of gold.” A talent was about 20 years worth of wages. If the average wage is around $45k, then that’s $900k. I don’t know how much a bag of gold is worth, but we’d have to multiply $900k by 10k for it to be accurate in talents. My iPhone calculator got an error when I did that. Ten thousand talents was more money than the known world had then, and ten thousand was the highest number in Greek. The point was actually that the amount of money the servant owed was unimaginable. Ten thousand bags of gold just doesn’t seem to be a good translation. This is an example of both the observation and the meaning of a word.

Another example is the word “power” in Romans 1:16: “For I am not ashamed of the gospel, for it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes, to the Jew first and also to the Greek.” The word for “power” in Greek is dynamis, from which we get the word “dynamite.” Some today, even popular commentators, say that the gospel, like dynamite, blows up sin. The problem with this view is that dynamite didn’t exist in the first century, so that can’t be what Paul meant. It simply means “power” or “ability.” This is a good example of what not to do in interpretation: import a later meaning into an earlier word. Remember, a text can’t mean what it never meant. This particular issue is called the fallacy of reverse etymology (etymology is the study of how words change over time) or anachronism.

Don’t know Greek? There are tools to help. Let me illustrate with a couple that I used before I studied Greek. I used to listen to a popular teacher and in one of his sermons he quoted Acts 2:24 to argue that Jesus went to hell. The text says this: “God raised him up, loosing the pangs of death, because it was not possible for him to be held by it” (the KJV from which he was using says “pains”). According to this teacher, since Jesus was in pain, then he must have been suffering, which wouldn’t have happened in heaven, so he must have been in hell. I was looking at that passage one day in my newly purchased Hebrew and Greek study Bible that used Strong’s Dictionary number system. The word “pain” had a number by it, so I looked it up. It said the word was “odin.” I also had just gotten the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (this is not an endorsement of TDNT as it is said to be pretty liberal, but it can be helpful in some ways), and looked up the word there. Basically, TDNT said that the word referred to birth pain, and that Peter was making an analogy here between a woman not being able to hold her baby in, but at the right time she gives birth, and death not being able to hold Jesus, but at the right time was forced to let go of him. It does not mean Jesus was in pain. Lessons: look words up. Get some tools.

But, as mentioned, word studies are not the only aspect of Bible study. When doing interpretation, we have to not only examine the meaning of particular words, but how words relate to other words. The former is merely grammar and the latter is syntax. This requires a knowledge of grammar as well as parts of speech and how words relate to each other. This is why simple word studies, while obviously useful, is not the only part of the game. Words aren’t in isolation, but relate to other words. Let me give you an example of how it is important to see how words relate to each other.

Several years ago in a Ph.D. class on philosophy of history, my professor, Mike Licona, said that we should not take the saints being raised in Matthew 27 literally because if we did, it would result in a problem in the text (this issue has since become a hot issue for him and the issue of inerrancy). Here’s the text: “And behold, the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom. And the earth shook, and the rocks were split. The tombs also were opened. And many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised, and coming out of the tombs after his resurrection they went into the holy city and appeared to many” (Matthew 27:51-53, ESV). Do you see the problem? I have read this passage for years and never noticed it. The context of the passage is Christ’s death. When was the curtain torn, and when did the earth shake? At his death—Friday. When did the tombs open and when were the saints raised? Friday. When does it say they came out of their tombs? After his resurrection—Sunday! That’s a natural reading of this translation. I haven’t seen any other English translations say it differently. The text seems to say that they were raised and the tombs were opened at the same time as the other events. But it seems to say that they didn’t come “out of their tombs until after his resurrection.”

I didn’t like this and was distracted by it. So, I stopped listening to the lecture (sorry Mike), and went to the Greek. Long story short, here was my solution: the word for “and” is kai in Greek and has several meanings, such as “even.” When it means “even” it tends to be emphatic/explanatory. In this case it could mean, “the saints were raised even coming out of their graves.” This seems to emphasize the physical nature of the event and that it wasn’t merely spiritual. Then, we could re-punctuate the sentence to read, “the saints who had fallen asleep were raised, even coming out of their tombs. After his resurrection, they went into the holy city and appeared to many.” I actually asked Mike if this was an acceptable answer as he knows Greek much better than me, and he said yes, as long as the word for “after” (meta) can start a new sentence. It can, an actually does a lot in narrative. Such a solution maintains proper Greek and English grammar and syntax. But it requires seeing how words relate to each other. It also requires observation and interpretation. (Some may object to such an answer as it appears to make the saints “resurrected” or first fruits before Jesus, but such is not necessary. The text does not imply they were raised immortal like Jesus. Remember, Jesus was not the first person raised from the dead. Elijah raised someone as did Jesus—Lazarus.)

I use this example to show a couple of things. One, don’t be married to any single English translation. Look at other translations (although I haven’t found an English translation that doesn’t have this particular problem here) and look, to whatever capacity you can, at the original languages. Two, the punctuation is not inspired (neither are the chapters and verses). In other words, read the text freshly and see if there are other ways to understand it and if the meaning changes.

One last note on interpretation and meaning. There can only be one meaning (although there can be many applications of that meaning: see below). While it is common for teachers to go around the room and ask their students, “What does this passage mean to you,” it is a bad question. It can’t mean to one person something that it doesn’t mean for all. It can have a different significance, but the actual meaning is fixed. (For a discussion on the issue argument the meaning is subjective or unattainable due to our biases, see my article on standard hermeneutics books as well as my article on historical objectivity.) While there are debates about what a given passage means, there can be only one right answer. It is up to studious interpreters to discover that meaning through the hermeneutical process. More could be said about interpretation, but let’s move on.

APPLICATION

Application is basically the “so what” part of the process. The question to ask here, after we have asked what does it say and what does it mean, is “how does this passage apply?” Unfortunately, sometimes people want to skip to this step first. Of course we have to know what the text says and means before we can ask how it applies to us. There are certain principles to keep in mind when trying to apply the text. Perhaps it is best up front to state that the text does not always have an application for us. Sometimes the text is informative for us and tells us about what happened, but it doesn’t always have an application. When the text says something like, “this king did this, and then this,” there really is no application, just information. In such instances, it is important not to try to wring out an application when there really isn’t one. Having said this, it is important to point out that even if there is no direct application, as Paul says in 2 Timothy 3:16, all Scripture is “profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.”

It’s easy to apply commands: just do or don’t do something. Although, sometimes it’s hard to tell whether a command is meant to be for a certain culture and time or whether it’s mean to be universal. For example, is the issue of head coverings in 1 Corinthians 11 meant to be universal? What about men not having long hair in verse 14? Paul says in 1 Timothy 2:12-14, “I do not permit a woman to teach or to exercise authority over a man; rather, she is to remain quiet. For Adam was formed first, then Eve; and Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor.” Is Paul saying women shouldn’t teach or exercise authority over a man always, or just in that culture and time? Whatever that text means, the reasoning behind it seems to be universal. Paul gives two reasons for what he said: (1) the order of creation, and (2) who was deceived. If the reasons are universal, then the prohibition would seem to be so as well.

Things aren’t as straightforward with narrative. We have to be careful to not make a description into a prescription. Narrative simply is a narration of what happened. Of course, it can contain other genres, but when we are looking at pure narrative and not a command to us, we have to be careful how we apply the text, if it can be applied. If it is simply a description of what happened, we can’t necessarily make it a prescription of what should happen. For example, the fact that Gideon put out a fleece to discern God’s will is not a command for us to. The fact that Elijah and other people in the OT were called supernaturally by God does not mean we can say that’s how God normally operates or “calls” people today. Here are some other pitfalls to avoid with application:

Analogizing: analogizing is what we just referred to with the call of Elijah. Just because God called Elijah does not mean that he calls us. This “call” is often analogized between Israel’s prophets and people today, but such an application is illicit. We simply can’t say that because God did something in ancient Israel that he does so today.

Allegorizing: Allegorizing is when we take a literal event and make the application allegorical. For example, we can talk about the person who “loosed his donkey for Jesus” when he entered Jerusalem. I once heard someone say he heard a pastor talk about “loosing your donkey for Jesus.” I guess that’s supposed to mean you are making what you have available for Jesus, but the text is talking about an event that actually happened. It is not a command.

Spiritualizing: Spiritualizing is similar to allegorizing. It takes literal events and gives a spiritual significance. A popular example of this is to present the story of Jesus calming the storm for the disciples and say “Jesus stills the storms of life.” There are a few problems with this. One is that this was a literal storm and was not meant to say that Jesus actually stills the storms of life. It isn’t talking about spiritual storms or tough times: it’s talking about a storm! Secondly, Jesus doesn’t still the storms of life if that means that he stops the storm like he did in the story. To say that he stills the storms of life is not only to state something that is false but to endanger someone’s faith who expects him to still his storms.

So what do we do to apply the text? One thing is to do what the text says to do if it is issuing a command. If it’s narrative, it’s to see what universal principle can be applied. In the story of David and Goliath, it is a spiritualization to say that we should go and slay the Goliaths in our lives. The biblical passage is talking about a literal person named Goliath. It is not giving a command, but describing something that actually happened. But we can glean universal principles. In this story that principle could be that God is faithful to the promises he makes and to his covenant. Here are some other principles from which to see how to apply the text:

- Is there an example for me to follow?

- Is there a sin to avoid?

- Is there a promise to claim?

- Is there a prayer to repeat?

- Is there a command to obey?

- Is there a condition to meet?

- Is there a verse to memorize?

- Is there an error [theological] to mark?

- Is there a challenge to face? (Howard Hendricks, Living by the Book, chapter 44)

The New International Application Commentary is an excellent commentary series to use to bridge the gap between the biblical times and ours to see if and how the text can be applied.

One last word about application: while the meaning is one, the application can be many since there are many situations in which to apply the text.

TOOLS FOR STUDY

If one is going to study the Bible, it is best to understand the tools that are available. Resources that this 3-step method is based on include Methodical Bible Study and Living by the Book (Living by the Book has a workbook).The most important tool is the Bible itself. There are hundreds of English translations of the Bible but there are generally 3 categories of translation philosophies: essentially literal (A.K.A. formal equivalence), dynamic equivalence (A.K.A. functional equivalence), and paraphrase. It is very important to use an essentially literal Bible for Bible study (see Translating Truth: The Case for Essentially Literal Bible Translation for a discussion on this), and I would argue for reading it too, but a good dynamic equivalent translation can be ok for reading. Paraphrases have even been recommended by good interpreters, but mainly to see the general sense of the passage. The front matter in your Bible should explain what translational philosophy it holds to. Essentially literal Bibles include the King James Version, The New King James Version, the New American Standard Bible, the English Standard Version, the Christian Standard Version, and the like. Dynamic equivalent translations include the New International Version, the Good News Bible, and the New English Translation. (The NET is worthwhile for its 60,000+ notes, and is available free at Bible.org.) Paraphrases include The Message, The Living Bible, and as I like to point out to my students, the Cotton Patch Gospel, that tells the story of Jesus from the vantage point of southerners in the U. S. (he is born in Gainesville, GA and escapes to Mexico).

Then there are commentaries. Commentaries are useful in many ways, but ideally should be consulted after your own study so you aren’t biased in a certain direction. There are two basic types of commentaries: critical (technical) and non-critical (non-technical). A commentary is critical if it discusses textual issues such as variations between different manuscripts of the original languages, or discusses the original languages in general. Some commentaries go into a great deal of detail and others don’t. Sometimes you just need a brief overview of an issue. For that I recommend The Bible Knowledge Commentary, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, the Tyndale Old Testament Commentary and the Tyndale New Testament Commentary (as a set here). The NIV Application Commentary is another non-technical commentary. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament, and The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (as a set here) is also very good. It is non-technical in the text but has technical/critical information in the notes. The IVP Bible Background Commentary (separate for OT and NT) is good for giving . . . the background, as are the The Lexham Geographical Commentary on the Gospels, The Lexham Geographical Commentary on Acts through Revelation, and The New Testament in Antiquity. There are actually commentaries on commentaries. These are basically long annotated biographies but with more information on the pluses and minuses of each set. See for example the Old Testament Commentary Survey,the New Testament Commentary Survey, and Commentary and Reference Survey. For a free and very useful resource, see Daniel Akin’s “Building a Theological Library.” It is not necessary to buy a complete set. As the commentary surveys and and Akin’s site show, some commentaries in a set are better than others, thus, it might be more beneficial if cost is an issue to buy certain individual commentaries. It is also important to pick up a good Bible dictionary and encyclopedia. There are a number of those in each category.

I can’t have a section on study tools and not mention Logos. There are many electronic software programs for Bible study. I have used Logos since 2004 and don’t want to try to do Bible study without it. I have required Logos in a couple of my classes as well, and the students love it too. Not only does it offer original language tools, it has incredibly complex search capabilities for the Bible, as well as the other books in your Logos library. And it is just that: a library. They have tens of thousands of books and tools. Other programs are good and there are debates about which is best, but I have used and love Logos. Others programs are BibleWorks, Olive Tree, or Accordance (only for Mac). Good free software is Blue Letter Bible and e-Sword.

CONCLUSION

What has been said hardly scratches the surface of biblical interpretation. It is certainly incomplete, but only mean to give some pointers and hopefully motivation for doing Bible study. This article is not meant to make Bible study seem hard, but to show that it takes work and offer some hopefully helpful tips. If you want to understand this system better, I encourage you to get Methodical Bible Study and/or Living by the Book. Thanks for reading, and please subscribe!

Recommended resources related to the topic:

Why We Know the New Testament Writers Told the Truth by Frank Turek (mp4 Download)

The Top Ten Reasons We Know the NT Writers Told the Truth mp3 by Frank Turek

Counter Culture Christian: Is the Bible True? by Frank Turek (Mp3), (Mp4), and (DVD)

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

J. Brian Huffling, PH.D. have a BA in History from Lee University, an MA in (3 majors) Apologetics, Philosophy, and Biblical Studies from Southern Evangelical Seminary (SES), and a Ph.D. in Philosophy of Religion from SES. He is the Director of the Ph.D. Program and Associate Professor of Philosophy and Theology at SES. He also teaches courses for Apologia Online Academy. He has previously taught at The Art Institute of Charlotte. He has served in the Marines, Navy, and is currently a reserve chaplain in the Air Force at Maxwell Air Force Base. His hobbies include golf, backyard astronomy, martial arts, and guitar

Original blog: https://bit.ly/3xgtCia