This post presents evidence against Mormonism/LDS in three main areas. The first is in the area of science. The second is in the area of philosophy. And the third is in the area of history.

The scientific evidence

First, let’s take a look at what the founder of Mormonism, Joseph Smith, believes about the origin of the universe:

“The elements are eternal. That which had a begginning will surely have an end; take a ring, it is without begginning or end – cut it for a begginning place and at the same time you have an ending place.” (“Scriptural Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith,” p. 205)

“Now, the word ‘create’ came from the word baurau which does not mean to create out of nothing; it means to organize; the same as a man would organize materials and build a ship. Hence, we infer that God had materials to organize the world out of chaos – chaotic matter, which is an element, and in which dwells all the glory. Element had an existence from the time he had. The pure principles of element are principles which can never be destroyed; they may be organized and re-organized, but not destroyed. They had no beggining, and can have no end.”

(“Scriptural Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith,” p. 395)

A Mormon scholar named Blake Ostler summarizes the Mormon view in a Mormon theological journal:

“In contrast to the self-sufficient and solitary absolute who creates ex nihilo (out of nothing), the Mormon God did not bring into being the ultimate constituents of the cosmos — neither its fundamental matter nor the space/time matrix which defines it. Hence, unlike the Necessary Being of classical theology who alone could not not exist and on which all else is contingent for existence, the personal God of Mormonism confronts uncreated realities which exist of metaphysical necessity. Such realities include inherently self-directing selves (intelligences), primordial elements (mass/energy), the natural laws which structure reality, and moral principles grounded in the intrinsic value of selves and the requirements for growth and happiness.” (Blake Ostler, “The Mormon Concept of God,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 17 (Summer 1984):65-93)

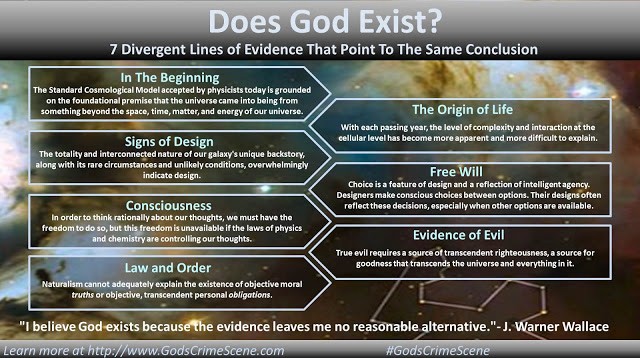

So, Mormons believe in an eternally existing universe, such that matter was never created out of nothing, and will never be destroyed. But this is at odds with modern cosmology.

The Big Bang cosmology is the most widely accepted cosmology of the day. It denies the past eternality of the universe. This peer-reviewed paper in an astrophysics journal explains. (full text here)

Excerpt:

The standard Big Bang model thus describes a universe which is not eternal in the past, but which came into being a finite time ago. Moreover,–and this deserves underscoring–the origin it posits is an absolute origin ex nihilo. For not only all matter and energy but space and time themselves come into being at the initial cosmological singularity. As Barrow and Tipler emphasize, “At this singularity, space and time came into existence; literally nothing existed before the singularity, so, if the Universe originated at such a singularity, we would truly have a creation ex nihilo.”

[…] On such a model the universe originates ex nihilo in the sense that at the initial singularity it is true that There is no earlier space-time point or it is false that Something existed prior to the singularity.

Christian cosmology requires such a creation out of nothing, but this is clearly incompatible with what Mormons believe about the universe. The claims about the universe made by the two religions are in disagreement, and we can test empirically to see who is right, using science.

Philosophical problems

Always Have a Reason contrasts two concepts of God in Mormonism: Monarch theism and Polytheism. It turns out that Mormonism is actually a polytheistic religion, like Hinduism. In Mormonism, humans can become God and then be God of their own planet. So there are many Gods in Mormonism, not just one.

Excerpt:

[T]he notion that there is innumerable contingent “primal intelligences” is central to this Mormon concept of god (P+M, 201; Beckwith and Parrish, 101). That there is more than one god is attested in the Pearl of Great Price, particularly Abraham 4-5. This Mormon concept has the gods positioned to move “primal intelligences along the path to godhood” (Beckwith and Parrish, 114). Among these gods are other gods which were once humans, including God the Father. Brigham Young wrote, “our Father in Heaven was begotten on a previous heavenly world by His Father, and again, He was begotten by a still more ancient Father, and so on…” (Brigham Young, The Seer, 132, quoted in Beckwith and Parrish, 106).

[…] The logic of the Mormon polytheistic concept of God entails that there is an infinite number of gods. To see this, it must be noted that each god him/herself was helped on the path to godhood by another god. There is, therefore, an infinite regress of gods, each aided on his/her path to godhood by a previous god. There is no termination in this series. Now because this entails an actually infinite collection of gods, the Mormon polytheistic concept of deity must deal with all the paradoxes which come with actually existing infinities…

The idea of counting up to an actual infinite number of things by addition (it doesn’t matter what kind of thing it is) is problematic. See here.

More:

Finally, it seems polytheistic Mormonism has a difficulty at its heart–namely the infinite regress of deity.

[…] Each god relies upon a former god, which itself relies upon a former god, forever. Certainly, this is an incoherence at the core of this concept of deity, for it provides no explanation for the existence of the gods, nor does it explain the existence of the universe.

Now let’s see the historical evidence against Mormonism.

The historical evidence

J. Warner Wallace explains how the “Book of Abraham,” a part of the Mormon Scriptures, faces historical difficulties.

The Book of Abraham papyri are not as old as claimed:

Mormon prophets and teachers have always maintained that the papyri that was purchased by Joseph Smith was the actual papyri that was created and written by Abraham. In fact, early believers were told that the papyri were the writings of Abraham.

[…] There is little doubt that the earliest of leaders and witnesses believed and maintained that these papyri were, in fact, the very scrolls upon which Abraham and Joseph wrote. These papyri were considered to be the original scrolls until they were later recovered in 1966. After discovering the original papyri, scientists, linguists, archeologists and investigators (both Mormon and non-Mormon) examined them and came to agree that the papyri are far too young to have been written by Abraham. They are approximately 1500 to 2000 years too late, dating from anywhere between 500 B.C. (John A. Wilson, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Summer 1968, p. 70.) and 60 A.D. If they papyri had never been discovered, this truth would never have come to light. Today, however, we know the truth, and the truth contradicts the statements of the earliest Mormon leaders and witnesses.

The Book of Abraham papyri do not claim what Joseph Smith said:

In addition to this, the existing papyri simply don’t say anything that would place them in the era related to 2000BC in ancient Egypt. The content of the papyri would at least help verify the dating of the document, even if the content had been transcribed or copied from an earlier document. But the papyri simply tell us about an ancient burial ritual and prayers that are consistent with Egyptian culture in 500BC. Nothing in the papyri hints specifically or exclusively to a time in history in which Abraham would have lived.

So there is a clear difference hear between the Bible and Mormonism, when it comes to historical verification.

Further study

If you want a nice long PDF to print out and read at lunch (which is what I did with it), you can grab this PDF by Michael Licona, entitled “Behold, I Stand at the Door and Knock.“

Original Blog Source: http://bit.ly/324GEPv