Por Jonathan McLatchie

Una prueba de fuego común para la ortodoxia cristiana es la adhesión a la doctrina de la inerrancia bíblica, que sostiene que el texto bíblico, en los autógrafos originales, está completamente libre de errores en todo lo que afirma. La doctrina de la inerrancia se desarrolla y define cuidadosamente en la Declaración de Chicago sobre la Inerrancia Bíblica de 1978, que se puede encontrar aquí. En este artículo, voy a explorar los conceptos de la inspiración y la inerrancia de las Escrituras y a desarrollar cuidadosamente mi comprensión actual de este tema, y en particular cómo se relaciona con mi método apologético evidencialista. En pocas palabras, aunque defiendo la inspiración de las Escrituras y las considero altamente fiables, no veo que la inerrancia pueda deducirse de las Escrituras, al menos no con la suficiente claridad como para justificar un dogmatismo sobre el tema. En mi opinión, aunque hay algunos casos en las Escrituras que considero candidatos a errores menores, se puede suponer con seguridad que se hicieron de buena fe, y de ninguna manera ponen en duda la confiabilidad general de las Escrituras.

Para empezar, me gustaría invitar al lector a reflexionar sobre los conceptos de inspiración e inerrancia y lo que éstos sostienen.

16 Toda Escritura es inspirada por Dios y útil para enseñar, para reprender, para corregir, para instruir en justicia, 17 a fin de que el hombre de Dios sea perfecto, equipado para toda buena obra. (2 Tim 3:16-17).

La Biblia afirma aquí muy claramente que toda la Escritura es inspirada por Dios, y para descartar cualquier confusión, quiero afirmar muy claramente que mantengo esta declaración. Cuando piensas en el significado de “inspirado por Dios”, ¿qué te viene a la mente? ¿Evoca imágenes de Dios, a través de su Espíritu, dictando de alguna manera las palabras exactas, la sintaxis y el flujo argumental a las personas para que las escribieran; en otras palabras, que cada detalle de los libros de la Biblia fue determinado por Dios para que fuera exactamente como lo poseemos ahora? Podemos llamar a esto la “teoría del dictado” de la inspiración. Si esta hipótesis es la correcta, ¿qué opina del hecho de que, por ejemplo, los cuatro evangelios revelen diferentes personalidades autorales? De hecho, los distintos autores bíblicos suelen tener más gusto por determinadas palabras que por otras (como el uso frecuente que hace Marcos de la palabra εὐθὺς, que significa “inmediatamente”). O ¿por qué cree que Dios le dictó a Pablo que le pidiera a Timoteo que trajera su capa (2 Tim 4:13)? En Romanos 16:22, Tercio, el escriba de Pablo, interviene: “Yo, Tercio, que escribo esta carta, os saludo en el Señor.” La Escritura registra incluso un lapsus de memoria, ya que Pablo anota: “También bauticé a los de la casa de Estéfanas; por lo demás, no sé si bauticé a algún otro” (1 Cor 1:16). Además, el texto bíblico utiliza diferentes estilos literarios, desde el lenguaje realista de un campesino hebreo (Amós) hasta la poesía exaltada de Isaías. La Biblia también revela un abanico de diferentes emociones humanas, como la “gran tristeza” (Rom 9:2), la ira (Gal 3:1), la soledad (2 Tim 4:9-16) y la alegría (Fil 1:4).

Como tal vez puedas ver ya, la cuestión de lo que significa que la Escritura haya sido inspirada por Dios no está tan clara como podría parecer a primera vista. Por supuesto, para el erudito y el teólogo, esto no será una novedad, ya que la teoría del dictado de la inspiración ha sido ampliamente rechazada desde hace tiempo entre los pensadores cristianos, en gran medida por las razones expuestas anteriormente, entre otras muchas. Más adelante en este artículo, ofreceré mi opinión personal sobre lo que significa que la Biblia sea la palabra inspirada de Dios. Pero por ahora, volvamos a la cuestión de la inerrancia y examinemos qué es y si se puede deducir de la propia Biblia.

Inerrancia fuerte vs. débil

Distingo entre una forma fuerte de inerrancia (lo que a veces llamo inerrancia dogmática o a priori) y una forma débil de inerrancia (lo que a veces llamo inerrancia inductiva). La Declaración de Chicago refleja la forma fuerte de inerrancia, según la cual un cristiano fiel no puede admitir, ni siquiera en principio, ningún error bíblico. En su forma más fuerte, este punto de vista establece una visión extremadamente frágil de las Escrituras, que esencialmente insinúa que si se identificara un error en la Biblia, se demostraría que el cristianismo es falso. Aunque esto rara vez se afirma de forma tan explícita, a menudo está implícito. Norman Geisler, por ejemplo, defiende una forma fuerte de inerrancia, según la cual la Biblia no sólo no contiene errores, sino que no puede contenerlos.[1] Generalmente, cuando alguien pregunta si tú afirmas la inerrancia, tiene en mente esta forma fuerte de inerrancia.

Esto pone una vara muy baja para que el escéptico ofrezca razones suficientes para rechazar el cristianismo, ya que la Biblia es un gran libro con muchas miles de afirmaciones históricas que pueden ser evaluadas críticamente. Esto, a su vez, hace que los cristianos pierdan su fe, ya que la duda sobre la inerrancia se toma a menudo no sólo como un impulso para pensar más cuidadosamente sobre la naturaleza de la inspiración, sino como una razón de peso para reconsiderar la verdad de la cosmovisión cristiana en su conjunto. Aunque los defensores de esta forma fuerte de inerrancia suelen argumentar que la inspiración divina de las Escrituras implica su inerrancia, esta línea de razonamiento puede emplearse en dos direcciones: es decir, en la medida en que la doctrina de la inspiración implica la inerrancia, la demostración exitosa de probables errores en las Escrituras es epistémicamente relevante para la cuestión de si el texto bíblico es de hecho inspirado. En otras palabras, si es cierto que la inspiración implica la inerrancia, entonces no sólo los argumentos a favor de la inspiración proporcionan pruebas que confirman la inerrancia, sino que los argumentos contra la exactitud de las afirmaciones contenidas en la Biblia también proporcionan pruebas que desconfirman la inspiración.

Un punto de vista alternativo, que considero más razonable, es la forma débil de inerrancia, que deja abierta la posibilidad de descubrir que hay errores en las Escrituras, pero manteniendo que no hay errores de hecho (al igual que un libro de texto universitario podría en principio contener errores, pero de hecho puede no tenerlos). Esta última perspectiva es la que más se acerca a mi punto de vista, aunque creo que hay un puñado de detalles relatados por la Escritura para los que se puede argumentar razonablemente, teniendo en cuenta todas las cosas, que un error es la mejor explicación.

Las consecuencias de la demostración exitosa de errores en la Escritura

Me ocuparé ahora de evaluar las consecuencias epistémicas de la identificación de uno o varios errores en la Escritura. Si eres de la opinión de que no hay errores en las Escrituras, te pido que consideres esta cuestión simplemente como una hipótesis. Hay que reconocer que una demostración de la falsedad de la inerrancia constituiría una prueba contra la inspiración y, a su vez, contra el cristianismo, ya que hay que admitir que existe una cierta tendencia a la inerrancia si se sostiene que un libro está inspirado divinamente en algún sentido significativo, aunque no estoy convencido de que la inspiración implique necesariamente la inerrancia, dependiendo del modelo de inspiración que se adopte (como trataré más adelante). Es importante distinguir aquí entre evidencia y prueba. Un dato puede tender a desconfirmar una proposición (es decir, reducir un poco su probabilidad) sin que ello implique su falsedad. En principio, las pruebas de desconfirmación pueden superarse con suficientes pruebas de confirmación, y es normal que las proposiciones tengan tanto pruebas de confirmación como de desconfirmación.[2]

A algunos les puede preocupar que se espere que Dios garantice que las Escrituras no tengan errores, aunque hayan llegado a nosotros por medios humanos. Sin embargo, dado que hay cierto nivel de ambigüedad, a veces, incluso con respecto a lo que decía el autógrafo original, parece ser una conclusión razonable que, en lo que respecta a Dios, no es importante que tengamos certeza sobre cada pequeño detalle reportado en el texto bíblico. Por ejemplo, es famoso que Jesús dijera desde la cruz: “Padre, perdónalos, porque no saben lo que hacen” (Lc 23:34). Sin embargo, muchos manuscritos importantes carecen de este versículo, lo que crea un cierto nivel de ambigüedad respecto a si este dicho forma parte del autógrafo original. Bruce Metzger comenta: “La ausencia de estas palabras en testigos tan tempranos y diversos… es muy impresionante y difícilmente puede explicarse como una escisión deliberada por parte de los copistas que, considerando la caída de Jerusalén como una prueba de que Dios no había perdonado a los judíos, no podían permitir que pareciera que la oración de Jesús había quedado sin respuesta”. Al mismo tiempo, el logion, aunque probablemente no forme parte del Evangelio original de Lucas, tiene indicios evidentes de su origen dominical, y fue conservado, entre dobles corchetes, en su lugar tradicional, donde había sido incorporado por copistas desconocidos en una época relativamente temprana de la transmisión del Tercer Evangelio”.[3] Con toda seguridad, la evidencia textual del Nuevo Testamento es suficiente para confiar en que lo que tenemos en nuestras Biblias es sustancialmente lo mismo que fue escrito por los autores originales, aunque quedan algunos casos en los que no se puede afirmar con seguridad la lectura original. La doctrina de la inerrancia, tal como se entiende convencionalmente, se aplica sólo a los autógrafos originales. Sin embargo, si la inerrancia era tan importante en los autógrafos originales, cabe preguntarse por qué Dios no preservó la inerrancia en la transmisión textual. Además, dado que, como ya he señalado, las Escrituras registran un lapsus de memoria (1 Cor 1:16), ¿no es al menos concebible que Dios pudiera potencialmente permitir que alguien recordara mal algo relativamente menor, como una secuencia precisa de eventos, etc.?

Dado que la inerrancia es una proposición de “todo o nada”, una vez que se ha admitido un solo error (y, por tanto, se ha falsificado la inerrancia), el peso probatorio contra el cristianismo que tienen las demostraciones posteriores de tipos de errores similares se reduce sustancialmente. Algunos errores propuestos tendrían mayores consecuencias que otros. Algunos errores afectarían sólo a la doctrina de la inerrancia (además de ser epistémicamente relevantes para la fiabilidad sustancial de determinados libros bíblicos), mientras que otros (como la inexistencia de un sólido Adán histórico, por ejemplo), al estar inextricablemente ligados a otras proposiciones centrales del cristianismo, serían mucho más graves.

Diferentes fuentes de errores y sus consecuencias

Otro factor que influye en la consecuencia epistémica de los errores bíblicos es el origen de los mismos. Las distorsiones deliberadas de los hechos, por ejemplo, tienen un efecto negativo mucho mayor tanto en la doctrina de que el libro es inspirado como en la fiabilidad sustancial del documento que los errores introducidos de buena fe. Una preocupación habitual de los inerrantistas es que admitir la presencia de un error en la Escritura conduce necesariamente a una pendiente resbaladiza, ya que entonces todo texto puede considerarse “en juego”. Esta objeción supone que no hay un modo fiable de discernir lo que es verdadero en la Escritura, a menos que asumamos que todo lo es. Sin embargo, esta crítica parece basarse en la falsa premisa de que suponer la inerrancia da una certeza del cien por ciento sobre cada afirmación de la Escritura. Esto, sin embargo, es falso, ya que se trata siempre de una valoración probabilística. Se puede objetar aquí que los que sostienen una forma fuerte de inerrancia hacen una estipulación a priori de la inerrancia, que implica una certeza del cien por ciento sobre la veracidad de cada afirmación de la Escritura. Sin embargo, si este es el caso, entonces tiene poco sentido hablar de pruebas a favor o en contra de la veracidad de cualquier afirmación proposicional concreta contenida en los relatos bíblicos, ya que las pruebas, por definición, aumentan o reducen la probabilidad de una hipótesis.

Además, creo que podemos demostrar inductivamente (a partir de un caso acumulativo basado en numerosas confirmaciones y corroboraciones de las Escrituras) que los documentos bíblicos se ajustan mucho a los hechos, son habitualmente veraces y sustancialmente dignos de confianza. Eso significa que cualquier afirmación que hagan estas fuentes constituye una prueba confirmatoria prima facie de que esos hechos ocurrieron realmente. Por lo tanto, está justificado creer incluso en detalles de las Escrituras para los que actualmente carecemos de una confirmación directa basada en la naturaleza de estos documentos. Un documento que ha demostrado ser sustancialmente fiable proporciona pruebas de su contenido, incluidas las proposiciones que no pueden ser confirmadas de forma independiente. Por lo tanto, si se demuestra que los Evangelios y Hechos son sustancialmente fiables (como yo sostengo), queda una base inductiva para confiar en los relatos incluso en aquellos asuntos que no pueden ser verificados independientemente. Este argumento inductivo no es incompatible con la existencia de algunos errores de buena fe. Se puede hacer un caso similar con respecto a los libros del Antiguo Testamento, aunque esto requiere mucho más trabajo para demostrarlo (ya que el Antiguo Testamento es mucho más grande que el Nuevo Testamento, y se refiere a eventos que están significativamente más alejados de nosotros en el tiempo que aquellos de los que se ocupa el Nuevo Testamento). Sin embargo, se pueden aducir importantes pruebas indirectas a favor de la fiabilidad del Antiguo Testamento (o al menos los lineamientos generales de la historia judía) a partir del testimonio de Jesús, suponiendo (como creo que es el caso) que los argumentos que confirman la identidad de Jesús como Dios encarnado (como el caso de su resurrección) se mantengan. Si, por otro lado, resultara que hay casos de fabricaciones deliberadas en los relatos bíblicos, entonces sí se produciría el problema de la pendiente resbaladiza que preocupa a los inerrantistas. Si los autores están dispuestos a distorsionar la verdad en una o más ocasiones, entonces uno podría preguntarse razonablemente qué más se ha tergiversado.

El punto de vista de la inerrancia fuerte también conlleva una posible pendiente resbaladiza

Además, la forma fuerte de inerrancia se encuentra con un problema similar, posiblemente más grave, de pendiente resbaladiza si las armonizaciones de uno emplean teorías de composición literaria de ficción (como las propuestas por Michael Licona).[4] Por ejemplo, si era una práctica aceptable en la época, y también una característica de los evangelios, que escenas enteras pudieran ser inventadas o detalles cambiados con el fin de hacer un punto teológico (como se sugiere en Why are there differences in the gospels? De Michael Licona), ¿cómo se puede estar seguro de que cualquier detalle en los evangelios no ha sido objeto de esta práctica? Afortunadamente, no creo que las pruebas que aporta Licona justifiquen sus conclusiones (por ejemplo, véase el libro de respuesta de Lydia McGrew The Mirror or the Mask (El espejo o la máscara) para una discusión y crítica detalladas de la tesis de Licona).[5]

En mi opinión, la opción epistémicamente menos costosa es adoptar el punto de vista que represento en este artículo. Por supuesto, también existe la opción de confesar la ignorancia y afirmar abiertamente que actualmente no sabemos cómo armonizar estos textos. Sin embargo, esto, en mi opinión, parece ir en contra del espíritu del evidencialismo, en el que uno opta por seguir las pruebas hasta donde le lleven.

¿Afirma la Escritura inequívocamente la inerrancia?

Vale la pena señalar que en ninguna parte de las Escrituras se afirma inequívocamente la inerrancia. Probablemente el texto más fuerte que sugiere la inerrancia es Juan 10:34 donde Jesús, refiriéndose al Antiguo Testamento, afirma que “la Escritura no se puede violar”. Aunque este texto crea un buen caso prima facie para la inerrancia, se supera con bastante facilidad si se descubren pruebas reales de errores fácticos concretos en las Escrituras. En ese caso, probablemente esté justificado interpretar que Jesús se refiere a los mandamientos de la Escritura y a sus enseñanzas morales y teológicas (cf. Mt 5:19; Jn 7:23), que es como está utilizando el Salmo en el contexto de este versículo. Se puede argumentar con más fuerza que Jesús afirmó la fiabilidad sustancial de las Escrituras del Antiguo Testamento, especialmente cuando Jesús se refiere a los acontecimientos. Por ejemplo, en Marcos 2:25-26, Jesús dice a los fariseos: “Y Él les dijo: ¿Nunca habéis leído lo que David hizo cuando tuvo necesidad y sintió hambre, él y sus compañeros, cómo entró en la casa de Dios en tiempos de Abiatar, el sumo sacerdote, y comió los panes consagrados que no es lícito a nadie comer, sino a los sacerdotes, y dio también a los que estaban con él?” Aunque este texto (y otros similares) sugiere con bastante fuerza que Jesús consideraba que la Biblia hebrea era sustancialmente digna de confianza, incluso esta interpretación está sujeta a dudas. Lo que me parece muy seguro es que Jesús afirmó los lineamientos generales de la historia judía tal y como los relatan las Escrituras hebreas. Hay que señalar que esto no requiere necesariamente que la propia Biblia hebrea sea fiable (aunque creo que las pruebas sugieren con fuerza que lo es; véase la lista de recursos más abajo).

Siempre que se interpreta un texto escrito, especialmente un texto antiguo, suele haber cierto grado de incertidumbre en la interpretación. El significado de algunos pasajes es más incierto que el de otros. Cuanto menor sea la probabilidad de nuestra interpretación, más fácil será superar el peso probatorio de esos textos con otras pruebas. De hecho, ésta es la base del principio hermenéutico común de que los pasajes menos claros deben interpretarse a la luz de los más claros. En cierto sentido, pues, todo está estratificado. ¿Implican las palabras de Jesús que el Antiguo Testamento es inerrante? Es plausible, pero no muy seguro. ¿Implican que todo el Antiguo Testamento es sustancialmente fiable? Bastante probable, pero todavía discutible. ¿Implican que David existió y que ciertos eventos particulares tuvieron lugar? Muy probable. Para resumir mi argumento, el caso de que Jesús creyera que David existió es obviamente mucho más fuerte que el caso de que creyera que todo el libro en el que ocurrió esa historia es fiable. Hay un buen caso para esto último, sin duda. Pero me parece poco probable que sea lo suficientemente fuerte como para que tengamos que desechar las pruebas tan convincentes de la identidad de Jesús (como el caso de la resurrección) si resulta que no es cierto. Algunos querrán señalar aquí que otro factor relevante es la probabilidad de que los informes de los evangelios ofrezcan un informe preciso de las cosas que dijo Jesús, en particular en relación con el Antiguo Testamento. Sin embargo, considero que la probabilidad aquí es bastante alta, dado el gran número de declaraciones que Jesús hace en los evangelios en relación con el Antiguo Testamento, combinado con la evidencia (que considero bastante sustancial) de que los evangelios proporcionan relatos sustancialmente fiables del ministerio y las enseñanzas de Jesús. Además, ciertos aspectos del ministerio de Jesús (como su cumplimiento del simbolismo de la Pascua, la relación de su muerte con la caída de Adán, su condición de Mesías davídico prometido en el Antiguo Testamento) implican que, al menos, los lineamientos generales de la historia judía, relatados en las Escrituras hebreas, son verdaderos. (Para evitar cualquier confusión, en este artículo no estoy discutiendo la fiabilidad del Antiguo Testamento per se. Lo que estoy examinando es lo que significa para la fiabilidad del Antiguo Testamento el hecho de que Jesús mencione pasajes y personas del Antiguo Testamento).

Debido a la naturaleza religiosamente significativa del acontecimiento de la resurrección, la inerrancia y fiabilidad del Antiguo Testamento, así como la veracidad de los lineamientos generales de la historia judía tal como se relata en la Biblia, son epistémicamente relevantes para la probabilidad previa de la resurrección. Es común entre los apologistas afirmar que, si se pueden aducir pruebas suficientes para apoyar la proposición de que Jesús resucitó de entre los muertos (un acontecimiento que se considera, con razón, la reivindicación por parte de Dios de las auto proclamaciones mesiánicas y divinas de Jesús), entonces se deduce necesariamente que el Antiguo Testamento debe ser fiable, ya que Jesús afirmó la inspiración y la fiabilidad de la Biblia hebrea. Este argumento tiene algo de cierto, ya que el testimonio de Jesús proporciona una prueba indirecta que confirma la inspiración y la fiabilidad del Antiguo Testamento. Sin embargo, también hay que reconocer que este argumento puede aplicarse en ambas direcciones. Las demostraciones exitosas de la falsedad de la inerrancia, de la falta de fiabilidad del Antiguo Testamento y de la falsedad de los lineamientos generales de la historia judía relatados en la Biblia hebrea serían evidencias indirectas que desconfirmarían la resurrección (por la vía de reducir la probabilidad previa -es decir, la probabilidad de que Jesús resucitara dada sólo la información de fondo-), aunque su valor probatorio para desconfirmar la resurrección sería variable.

Un matiz importante que a menudo se pasa por alto es que no es necesario que el texto del Antiguo Testamento sea fiable para que el argumento general, o incluso los detalles particulares, sean correctos (aunque yo mismo sostengo que la Biblia hebrea es un conjunto de documentos sustancialmente fiables y, por lo tanto, la siguiente discusión debe tomarse como puramente hipotética). Si se demostrara con éxito que los libros que componen la Biblia hebrea no son fiables desde el punto de vista histórico, se eliminaría la evidencia directa de los acontecimientos en cuestión, mientras que se dejaría intacta la evidencia indirecta (es decir, el testimonio de Jesús combinado con el caso de su deidad). Los documentos poco fiables son como el “ruido”, lo que significa que sus afirmaciones proposicionales no proporcionan por sí mismas pruebas de lo que afirman. Sin embargo, de esto no se deduce que la mayoría, todas o incluso las afirmaciones más destacadas contenidas en esos documentos sean falsas. Así, aunque hubiera pruebas positivas que revelaran que el Antiguo Testamento no es fiable, esto no sería necesariamente una razón positiva para concluir que, por ejemplo, David no existió o que el Éxodo no ocurrió. Una novela histórica puede ser una fuente de información poco fiable para un historiador, pero una demostración en ese sentido no implicaría que varias proposiciones de la novela no pudieran deducirse como verdaderas por otros motivos. Así, aunque las fuentes históricas contenidas en el Antiguo Testamento resultasen poco fiables, se podría concluir racionalmente, como mínimo, que las proposiciones clave del Antiguo Testamento son ciertas sobre la base de una prueba indirecta, a saber, el testimonio de Jesús. Por lo tanto, soy de la opinión de que para reducir la probabilidad previa de la resurrección lo suficiente como para superar el caso acumulativo positivo a favor de la misma, habría que hacer algo más que simplemente mostrar la falta de fiabilidad del Antiguo Testamento: también habría que montar un caso positivo fuerte de que las proposiciones importantes (como la historicidad de Adán; la aparición de Dios a Abraham, Isaac y Jacob; el Éxodo; la existencia del rey David y las promesas de Dios a él, etc.) son falsas. La carga de la prueba asociada a la negación de esas proposiciones sería un reto a cumplir.

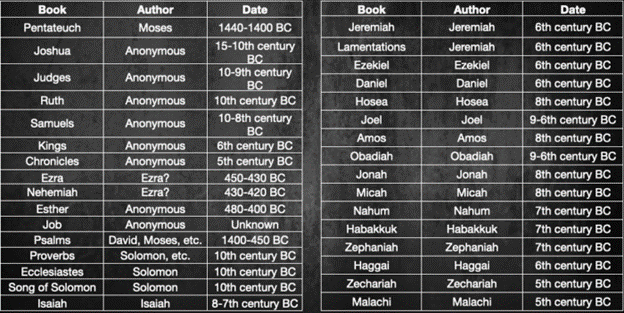

Para que conste, creo que se puede hacer un caso convincente para la fiabilidad sustancial del Antiguo Testamento, y la discusión anterior debe ser tomada puramente hipotética!!!!!!!!!!!!!. Para cualquier persona interesada en este caso, aquí hay una lista de libros y recursos que recomendaría:

- Kenneth A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament(Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006).

- Walter C. Kaiser Jr., The Old Testament Documents: Are They Reliable & Relevant? (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2001), 92–93.

- Clive Anderson y Brian Edwards, Evidence for the Bible (Leominster: Day One, 2014).

- Daniel I. Block, ed., Israel — Ancient Kingdom or Late Invention? (North Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing Group, 2008).

- James K. Hoffmeier, Alan R. Millard, & Gary A. Rendsburg, ed. “Did I Not Bring Israel Out of Egypt?” Biblical, Archaeological, and Egyptological Perspectives on the Exodus Narratives, Bulletin for Biblical Research Supplement 13 (University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns, 2016).

- Gleason Archer Jr., A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, 3rd. ed. (Chicago: Moody Press, 1994).

- Titus Kennedy, “Is the Exodus History? A Conversation with Dr. Titus Kennedy?”, entrevistado por Jonathan McLatchie, Apologetics Academy, May 21, 2020, video, https://youtu.be/czUyRQ6rUXw

- Stephen C. Meyer, “Is the Bible Reliable? Building the Historical Case,” TrueU Season 2, Focus on the Family, 2011, video series,

https://www.amazon.com/How-Archaeology-Backs-New-Testament/dp/B00XWWV3O0/

Hay muchos otros buenos recursos, por supuesto, pero esto debería ser más que suficiente para que empieces a investigar.

Un modelo propuesto de inspiración bíblica

Si la inerrancia es falsa, ¿cómo puede afectar eso a la doctrina de la inspiración? Está claro que el concepto bíblico de inspiración no es como el concepto musulmán, que realmente implica la inerrancia en sentido fuerte. La opinión tradicional entre los musulmanes suníes es que el Corán ha sido inscrito en tablas en el Paraíso para toda la eternidad (Surah 85:22). Todos los musulmanes consideran que el Corán fue dictado por el ángel Gabriel al supuesto profeta Mahoma durante un periodo de veintitrés años, desde diciembre del 609 hasta el 632 d.C., cuando murió Mahoma. Según el punto de vista islámico, el Corán representa realmente el discurso directo de Alá. Podemos llamar a esta visión de la inspiración “teoría del dictado”. Históricamente, los cristianos no han sostenido la teoría del dictado de la inspiración, y por muy buenas razones, ya que este punto de vista está plagado de problemas muy graves, como se ha comentado anteriormente.

Si se descarta la teoría del dictado, ¿qué interpretación de la inspiración debe preferirse? Desafortunadamente, la Escritura no es nada clara en cuanto a lo que significa exactamente que la Escritura sea, como dijo Pablo, θεόπνευστος (“inspirada por Dios”) (2 Tim 3:16). Mi teoría de la inspiración, a la que no puedo concebir una alternativa plausible después de que la teoría del dictado está fuera de la mesa, es que Dios designó a ciertos individuos -apóstoles y profetas- a los que impartió ideas reveladoras especiales. Luego, encomendó a esas personas que escribieran lo que Dios les había dado a conocer en su propia voz. Esto significa que, en principio, los mismos conceptos podrían haberse expresado con palabras completamente diferentes y seguirían teniendo la autoridad de ser la Palabra de Dios. Por tanto, en mi opinión, no son las palabras de la Escritura las que están inspiradas, sino el significado de la Escritura. Por supuesto, hay excepciones en las que las Escrituras fueron dictadas por Dios (en particular, los diez mandamientos y los pasajes “Así dice el Señor”). Debido a la naturaleza de esos pasajes, yo sostendría que esos son verdaderamente inerrantes en el sentido fuerte.

Una de las objeciones que he encontrado al punto de vista que propongo aquí es que implica que el centro de la inspiración son los autores y no las propias Escrituras, mientras que en 2 Timoteo 3:16-17 se afirma que es la Escritura la que es “inspirada por Dios”. Sin embargo, esta objeción me parece que es una división de opiniones. Evidentemente, sea cual sea el punto de vista de la inspiración que se adopte, son los autores los que son objeto de inspiración (ya que el texto bíblico fue escrito por hombres y el texto refleja las personalidades y estilos distintivos de sus autores humanos). Si uno se aleja de la teoría del dictado de la inspiración, como se ve obligado por muchos factores, entonces me parece que un escenario que es al menos similar al punto de vista que he propuesto es la única alternativa viable.

El caso de la armonización

Aunque no estoy comprometido con la inerrancia como cuestión de principios, soy un ávido defensor de la práctica de la armonización. Las fuentes que han demostrado ser sustancialmente fiables constituyen una prueba de sus afirmaciones. Esto es cierto tanto si se trata de un texto de importancia religiosa como de otro tipo. Por lo tanto, si uno identifica una aparente discrepancia entre fuentes fiables (como los evangelios), el curso de acción racional es buscar una forma plausible de armonizar esos textos. Aunque esta práctica se suele rechazar en la erudición bíblica, creo que el sesgo académico contra la armonización es bastante irracional. Considero que la armonización es una práctica académica buena y responsable, tanto si se trata de fuentes religiosas significativas como de fuentes seculares. Se debe permitir que las diferentes fuentes que se cruzan en su informe de un evento particular se iluminen y aclaren mutuamente. También creo que las fuentes que han demostrado ser altamente fiables deben recibir el beneficio de la duda cuando hay una aparente discrepancia. En mi opinión, en tales casos, se deben buscar armonizaciones razonables como primer puerto de escala y sólo se debe concluir que el autor está equivocado si las posibles armonizaciones son inverosímiles. Lydia McGrew expone bien este punto[6]:

La armonización no es un ejercicio esotérico o religioso. Los cristianos que estudian la Biblia no deben dejarse intimidar por la insinuación de que se dedican a la armonización sólo por sus compromisos teológicos y que, por tanto, están falseando los datos por razones no académicas. Por el contrario, cabe esperar que las fuentes históricas fiables sean armonizables, y normalmente lo son cuando se conocen todos los hechos. Intentar ver cómo encajan entre sí es un método extremadamente fructífero, que a veces incluso da lugar a conexiones como las coincidencias no diseñadas de las que se habla en Hidden in Plain View. Esta es la razón por la que persigo la armonización ordinaria entre las fuentes históricas y por la que a menudo concluyo que una armonización es correcta.

Los lectores que estén interesados en el caso de la sólida fiabilidad de los relatos evangélicos están invitados a leer otros artículos que he publicado sobre este tema o a escuchar esta entrevista.

Una consideración importante en lo que respecta a la evaluación de las armonizaciones, que a menudo se pasa por alto, es que el peso probatorio de un error o una contradicción propuestos en las Escrituras se relaciona no tanto con la probabilidad de cualquiera de las armonizaciones propuestas como con la disyunción de las probabilidades asociadas a cada una de las armonizaciones candidatas. Para poner un ejemplo simplista, si uno tiene cuatro armonizaciones que tienen cada una un 10% de probabilidad de ser correctas, entonces el peso probatorio del problema es significativamente menor que si sólo se tuviera una de ellas, ya que la disyunción de las probabilidades relevantes sería del 40%. Por lo tanto, el texto sólo tendría una probabilidad ligeramente mayor de ser erróneo que de no serlo (y los argumentos inductivos a favor de la fiabilidad sustancial pueden inclinar la balanza a favor de dar al autor el beneficio de la duda). En realidad, por supuesto, las matemáticas son bastante más complicadas que esto, ya que hay que considerar si alguna de las armonizaciones se superpone o se implica de tal manera que las probabilidades no pueden sumarse entre sí. Por supuesto, si algunos de los disyuntos tienen una probabilidad muy baja de ser correctos, entonces no serán de mucha ayuda.

Fuertes candidatos a errores en las Escrituras

En esta sección, quiero discutir un puñado de ejemplos de proposiciones históricas contenidas en las Escrituras que considero fuertes candidatos a ser errores reales en los autógrafos originales. A veces otros cristianos me disuaden de discutir públicamente las evidencias que tienden a desconfirmar el cristianismo, aunque yo sostengo que esas evidencias están suficientemente contrarrestadas por evidencias confirmatorias más fuertes y numerosas. El razonamiento de estos disuasores es que, al llamar la atención sobre los aspectos más problemáticos de las pruebas, corro el riesgo de hacer que la gente, quizá los jóvenes creyentes, duden de la verdad del cristianismo. Comprendo muy bien y aprecio esta preocupación. Tengo un afecto particular por los cristianos que luchan con dudas intelectuales y durante varios años he dirigido un servicio de asesoramiento en línea para los cristianos que luchan con dudas racionales. Sin embargo, creo que la integridad intelectual me obliga a dar a conocer los puntos fuertes y débiles de la interpretación cristiana de las evidencias relevantes, a expresar cómo interpreto yo los datos y a permitir que la gente llegue a sus propias conclusiones. El apologista no está llamado a asumir el papel de abogado defensor, comprometiéndose a defender la veracidad de su posición pase lo que pase. Más bien, el apologista debe asumir el papel de un periodista de investigación, informando para el consumo popular de los resultados de una investigación justa y equilibrada. Si no estamos dispuestos a hablar públicamente de las vulnerabilidades intelectuales de la posición cristiana, ¿qué nos diferencia de personas como el clérigo musulmán Yasir Qadhi, que recientemente dijo en una entrevista con Mohammed Hijab que las pruebas que desafían la narrativa estándar de la preservación del Corán no deben ser discutidas en público?

Por supuesto, esta actitud no se limita a la apologética religiosa, como ha puesto de manifiesto la reciente censura durante las elecciones estadounidenses por parte de los medios de comunicación y las redes sociales de información que podría disuadir a la gente de votar por Biden y Harris. En 2010, dos ateos, el filósofo Jerry Fodor y el científico cognitivo Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, publicaron un libro en el que planteaban varias cuestiones que consideraban problemas sin respuesta relacionados con la teoría de la evolución por selección natural de Darwin.[7] En el precio, señalan,

Más de un colega nos ha dicho que, aunque Darwin se equivocara sustancialmente al afirmar que la selección natural es el mecanismo de la evolución, no debemos decirlo. No, en todo caso, en público. Hacerlo es, aunque sea inadvertidamente, alinearse con las Fuerzas de la Oscuridad, cuyo objetivo es desprestigiar la Ciencia. No estamos de acuerdo. Creemos que la manera de incomodar a las Fuerzas de la Oscuridad es seguir los argumentos dondequiera que nos lleven, difundiendo la luz que uno pueda en el curso de hacerlo. Lo que hace que las Fuerzas de la Oscuridad sean oscuras es que no están dispuestas a hacer eso. Lo que hace que la Ciencia sea científica es que lo es.

Estoy muy de acuerdo con el espíritu de esos comentarios. De hecho, como en el caso de la evolución, si el cristianismo es verdadero (que estoy convencido de que lo es), no deberíamos temer que la gente esté expuesta a toda la información que necesita para formarse su propia opinión. Por supuesto, esto no justifica la imprudencia. Uno debe tener cuidado de hacer la debida diligencia en la realización de un análisis adecuado de las pruebas pertinentes antes de dejar constancia de las pruebas que son problemáticas, al igual que uno debe hacer antes de dejar constancia de las pruebas que confirman la verdad del cristianismo.

A continuación, expondré un pequeño puñado de casos en los que creo que se puede argumentar razonablemente que los relatos evangélicos son erróneos, aunque sostengo que todos esos ejemplos son explicables de forma plausible como el resultado de un error cometido de buena fe, y no de una distorsión deliberada de los hechos. Para los ejemplos que siguen estoy convencido de que la mejor explicación es una variación en la memoria de los testigos oculares. Aunque he seleccionado ejemplos para los que no creo que ninguna de las armonizaciones tradicionales funcione (o que sean, al menos, bastante menos plausibles que la hipótesis del error), estoy abierto a que me convenzan de lo contrario.

Nuestro primer ejemplo es la localización que hace Mateo de la maldición de la higuera y su vinculación con el día de la limpieza del Templo. Marcos 11:12 da a entender que la limpieza del templo tuvo lugar después de la maldición de la higuera, mientras que Mateo 21:18 da a entender que la maldición de la higuera tuvo lugar al día siguiente de la limpieza del templo. Aunque los antiguos a veces narraban los acontecimientos a-cronológicamente (es decir, sin precisión cronológica), no hay ninguna razón para creer que los antiguos consideraran una práctica aceptable narrar los acontecimientos históricos de forma discronológica (es decir, incluyendo marcadores temporales que tergiversan o engañan respecto a la cronología de los acontecimientos).

Nuestro segundo ejemplo es la cuestión del centurión que acude a Jesús en Mateo 8 frente a que él envía a Jesús a los ancianos de los judíos en Lucas 7. Los armonizadores tradicionales intentan a menudo establecer un paralelismo entre esto y pasajes como Mateo 27:26/Marco 15:15/Juan 19:1 en los que se nos dice que Pilato azotó a Jesús (cuando en realidad, sabemos que no fue el propio Pilato quien hizo la flagelación sino los soldados bajo su mando).[8] Sin embargo, en este último caso, sabemos que nadie habría pensado que Pilato azotó personalmente a Jesús, mientras que esto es muy diferente de lo que tenemos en el caso del centurión. En Mateo, hay indicios bastante claros (a mi entender) de que Mateo pensó que el centurión vino en persona. Lydia McGrew señala varios problemas con la armonización tradicional de estos textos: “La narración de Mateo es bastante unificada en su apariencia de que el centurión está presente personalmente. La afirmación final de que Jesús dijo al centurión: ‘Ve, y como creíste, te sea hecho’, donde la orden está en singular, es particularmente difícil de cuadrar con la solución agustiniana. Si el centurión estuviera en su casa enviando mensajeros a Jesús, no necesitaría ir a ninguna parte. Y si Jesús estuviera hablando con los mensajeros, no habría utilizado el singular.”[9] McGrew concluye, y yo me inclino a estar de acuerdo, que la explicación más sencilla de esta discrepancia es “una simple variación de memoria entre los testigos.”[10]

Un tercer caso es el aparente conflicto entre Juan 12:1 y Marcos 14:3, ya que Juan sitúa la unción en Betania seis días antes de la Pascua, mientras que Marcos parece situarla dos días antes de la Pascua. Juan da a entender que tuvo lugar poco después de la llegada de Jesús a Betania (antes de la entrada triunfal en Jerusalén), mientras que Marcos da a entender que tuvo lugar después de la entrada triunfal. Craig Blomberg propone que Marcos narra deliberadamente los acontecimientos a-cronológicamente por razones temáticas, ya que Jesús dice que la unción es para su entierro (Mc 14:8; Jn 12:7). Señala que “Marcos 14:3… está unido al versículo 2 simplemente por una kai (y) y pasa a describir un incidente que tiene lugar en algún momento no especificado mientras Jesús ‘estaba en Betania’. Una vez que observamos que tanto Marcos como Juan presentan a Jesús interpretando la unción como una preparación para su entierro, se puede entender por qué Marcos inserta el relato inmediatamente antes de una descripción de otros presagios de su muerte, incluyendo su última cena con los Doce.”[11] Otra idea, que también implica apelar a la narración a-cronológica, ha sido propuesta por el difunto Steve Hays, a saber, que Marcos pudo haber compuesto los versículos 14:1-2 y posteriormente interrumpir su escritura antes de volver a escribir sobre la unción en Betania como otro episodio ocurrido durante la semana de la Pasión (aunque sin intención de conectarlo con los versículos 1-2, que afirman que faltaban dos días para la Pascua).[12] Sin embargo, según la hipótesis de una narración cronológica, cabría esperar que Marcos proporcionara más información sobre lo que ocurrió el miércoles, antes de la discusión de la unción en Betania. En cambio, casi no hay narración en Marcos entre ese cuidadoso marcador cronológico y la unción en Betania. Todo lo que Marcos nos dice respecto a ese día es que “los jefes de los sacerdotes y los escribas buscaban la manera de prenderlo a escondidas y matarlo, pues decían: “buscaban cómo prenderle con engaño y matarle; porque decían: No durante la fiesta, no sea que haya un tumulto del pueblo” (Mc 14:1-2), pero Marcos ya ha indicado en el versículo 12:12 que “Y procuraban prenderle, pero temían a la multitud, porque comprendieron que contra ellos había dicho la parábola. Y dejándole, se fueron.” Lydia McGrew comenta[13],

Dado que Marcos introduce el día en el versículo 14:1, es de suponer que pretende narrar algunos acontecimientos sustanciales que sucedieron en ese día. ¿Por qué iba a hacer una referencia temporal tan explícita en el versículo 14:1, narrar sólo la decisión de los líderes judíos en ese día, interrumpir bruscamente para contar algo que había sucedido varios días antes, y luego volver en el versículo 10 a la narración de los acontecimientos del miércoles? Se trataría de un proceso de composición extremadamente entrecortado, casi como si ni siquiera hubiera leído lo que había escrito por última vez cuando empezó a narrar la cena en Betania. E incluso si ese fuera el caso, ¿por qué no tendría un mejor indicador de tiempo al volver al miércoles en el versículo 10? Marcos ha ido indicando los días en su narración de la Semana de la Pasión desde el domingo hasta el miércoles con bastante claridad (Marcos 11:11-12, 19-20, 13:1-3, 14.1). Sería sorprendente que de repente comenzara a narrar acronológicamente en el versículo 14:3, incluso como un artefacto de ruptura y reanudación de la escritura. Es mucho más sencillo considerar que la intención de Marcos es que todos los acontecimientos del principio del capítulo 14 ocurran el miércoles.

Un último ejemplo que voy a comentar aquí es el que considero la única discrepancia real entre los relatos de la natividad de Mateo y Lucas (tal vez trate otras supuestas discrepancias entre estos relatos, que me parecen poco convincentes, en un futuro artículo). Al parecer, Lucas desconoce la huida a Egipto que se relata en Mateo 2:13-15. Esto no sería un problema en sí mismo, ya que la omisión no es lo mismo que la negación, y Mateo y Lucas se basan evidentemente en fuentes diferentes (aunque complementarias). Sin embargo, Lucas 2:22-38 se refiere a la dedicación de Jesús en el templo y a la ceremonia de purificación. Cuando una mujer daba a luz un hijo, se la consideraba ceremonialmente impura durante cuarenta días (Lv 12:2-5). Después de este período, debía ofrecer un cordero de un año y una paloma o un pichón (Lev 12:6), aunque si era pobre podía ofrecer dos palomas o pichones (Lev 12:8). La ofrenda de María, por tanto, indica que ella y José eran pobres (Lc 2:24). Lucas 2:39 indica que “Habiendo ellos cumplido con todo conforme a la Ley del Señor, se volvieron a Galilea, a su ciudad de Nazaret.” El texto implica claramente que fue muy poco después de la purificación cuando volvieron a su casa, mientras que Mateo indica firmemente que la familia de Jesús permaneció en Belén durante un tiempo considerable después del nacimiento de Jesús y sólo volvió a Nazaret tras la huida a Egipto. ¿Se puede explicar esta aparente discrepancia? Personalmente, creo que la explicación que tiene más sentido es que las fuentes de Lucas (que pueden haber sido escritas, orales o una combinación de ambas) no contenían un relato de la venida de los magos, la matanza de los niños en Belén o la huida a Egipto. Creo que la principal fuente de Lucas para su relato de la natividad fue María. Es una conjetura razonable que María haya contado a Lucas la historia de Simeón y Ana en el templo (Lc 2:25-38) antes de pasar al siguiente relato diciendo algo así como “Y más tarde, cuando vivíamos en Nazaret, solíamos venir todos los años a Jerusalén a la fiesta de la Pascua”. Tal vez Lucas supuso de forma natural que habían regresado a Nazaret inmediatamente después de la presentación en el templo, y por ello escribió una transición que conectaba los dos relatos.

El problema de la disminución de las probabilidades

Un punto importante que a menudo se pasa por alto cuando se discuten las discrepancias evangélicas y los candidatos al error es el problema de la disminución de las probabilidades. Este problema tiene que ver con el hecho de que nunca tenemos la certeza absoluta de que un texto determinado no está equivocado, sino que se trata siempre de una evaluación probabilística que se basa en consideraciones tales como la fiabilidad general del texto en cuestión, los aspectos problemáticos del texto (como una aparente discrepancia con otras fuentes), las pruebas directas que influyen en la afirmación en cuestión, etc. Esto significa que si tenemos un conjunto de textos que tienen una probabilidad razonable de estar equivocados, la probabilidad de que todos los textos no contengan un error disminuye con los ejemplos sucesivos. Supongamos, por ejemplo, que tenemos un conjunto de cuatro aparentes discrepancias entre los relatos evangélicos (como he enumerado anteriormente). Supongamos hipotéticamente que cada uno de esos textos, considerado individualmente (teniendo en cuenta las armonizaciones propuestas y consideraciones como la fiabilidad general de los textos) tiene, por término medio, un 30% de probabilidades de contener un error. En ese caso, la probabilidad de que uno de ellos esté realmente en el error sería calculable por 1-0.74, que sería aproximadamente 0,76. Así pues, la demostración de que un texto individual tiene, en conjunto, más probabilidades de ser armonizable que de no serlo, no implica que no haya una alta probabilidad de que al menos algunos de esos textos estén de hecho en error.

El peso probatorio de las discrepancias aparentes y reales

Ya he escrito antes sobre el fenómeno de las variaciones conciliables, llamado así por el erudito anglicano del siglo XIX Thomas Rawson Birks.[14] Una variación conciliable se refiere a cuando existen dos relatos del mismo acontecimiento o, al menos, dos relatos que parecen cruzar el mismo territorio en algún punto y, a primera vista, parecen tan divergentes que resulta casi incómodo; pero luego, al reflexionar más, resultan ser conciliables de alguna manera natural después de todo. Cuando dos relatos parecen al principio tan divergentes que uno no está seguro de que puedan reconciliarse, eso es una prueba significativa de su independencia. Cuando, tras un examen más detallado o al conocer más información, resultan ser conciliables sin forzarlas, es casi seguro que se trata de relatos independientes que encajan. Las discrepancias reales entre los relatos, como las que he comentado anteriormente, también tienden a apoyar la independencia de los relatos. Por lo tanto, se podría decir que las discrepancias reales entre los relatos evangélicos tienen múltiples vectores epistémicos: son negativamente relevantes desde el punto de vista epistémico para la fiabilidad de los relatos y, al mismo tiempo, apoyan la independencia de las narraciones en sentido más amplio (y los relatos independientes que se solapan en relación con un acontecimiento constituyen una prueba de su verdad).

En alguna ocasión me han preguntado si, de forma similar al caso acumulativo que yo construiría para la fiabilidad sustancial de los evangelios y Hechos (a partir de coincidencias no diseñadas entre otras líneas de evidencia), se podría construir un caso acumulativo para su falta de fiabilidad a partir de las contradicciones entre los relatos evangélicos. Sin embargo, aparte del hecho de que las pruebas positivas son mucho más numerosas que el tipo de discrepancias que he documentado anteriormente, yo diría que existe una asimetría epistémica entre estas pruebas positivas y las negativas, es decir, las pruebas positivas que yo y otros hemos aducido (como las coincidencias no diseñadas) tienen una mayor fuerza probatoria que las aparentes discrepancias que existen entre los relatos evangélicos. Para ver si (y hasta qué punto) X cuenta como evidencia de H, hay que saber cómo se compara nuestra expectativa de X cuando H es verdadera con nuestra expectativa de X cuando H es falsa. Una vez que calibramos así nuestras expectativas, la apariencia de un paralelismo en los dos argumentos se evapora.

Tim McGrew y Lydia McGrew señalan varios casos en los que las fuentes antiguas, consideradas generalmente fiables, presentan varias discrepancias menores[15]:

Incluso un conocimiento superficial de los documentos que forman la base de la historia secular revela que los informes de los historiadores fiables, incluso de los testigos oculares, siempre muestran una selección y un énfasis y no pocas veces se contradicen abiertamente. Sin embargo, este hecho no destruye, ni siquiera socava significativamente, su credibilidad respecto a los principales acontecimientos que relatan. Casi ninguno de los dos autores está de acuerdo en el número de tropas que reunió Jerjes para su invasión de Grecia, pero la invasión y su desastroso resultado no están en duda. El relato de Floro sobre el número de tropas en la batalla de Farsalia difiere del propio relato de César en 150.000 hombres; pero nadie duda de que hubo tal batalla, ni de que César la ganó. Según Josefo, la embajada de los judíos al emperador Claudio tuvo lugar en el tiempo de la siembra, mientras que Filón la sitúa en el tiempo de la cosecha; pero que hubo tal embajada es incontrovertible. Los ejemplos de este tipo se pueden multiplicar casi de forma interminable.

Dado que la hipótesis de que un conjunto de documentos históricos es sustancialmente fiable predice que habrá pequeñas variaciones entre los relatos (como se observa cuando examinamos otros documentos que generalmente se consideran sustancialmente fiables), la observación de que efectivamente existen pequeñas variaciones entre dichos relatos no puede utilizarse como prueba significativa contra la fiabilidad de los mismos. El eminente jurista Thomas Starkie explica bien este punto[16]:

Es necesario observar aquí que las variaciones parciales en el testimonio de diferentes testigos, en puntos minúsculos y colaterales, aunque con frecuencia ofrecen al defensor adverso un tema para la observación copiosa, son de poca importancia, a menos que sean de una naturaleza demasiado prominente y llamativa para ser atribuida a la mera inadvertencia, falta de atención o defecto de memoria. Un gran observador ha señalado que “el carácter habitual del testimonio humano es la verdad sustancial bajo una variedad circunstancial”. Es tan raro que los testigos de una misma transacción coincidan perfecta y totalmente en todos los puntos relacionados con ella, que una coincidencia total y completa en cada detalle, lejos de reforzar su crédito, no pocas veces engendra una sospecha de práctica y concertación. La verdadera cuestión debe ser siempre, si los puntos de variación y discrepancia son de una naturaleza tan fuerte y decisiva como para hacer imposible, o al menos difícil, atribuirlos a las fuentes ordinarias de tales variedades, la falta de atención o de memoria.

El mismo principio puede aplicarse a los relatos evangélicos. Aunque los evangelios contengan algunas discrepancias menores en cuanto a detalles periféricos, de ello no se deduce que los relatos sean generalmente poco fiables, ya que conocemos muchos relatos fiables que contienen discrepancias.

Conclusión

A veces me han preguntado si afirmo la doctrina de la inerrancia, y me temo que mi respuesta requiere más matices que un simple “sí” o “no”. Ambas respuestas invitan a ciertas suposiciones sobre mis puntos de vista que deben ser desenredadas y aclaradas. Si uno responde “sí”, el interrogador puede suponer que el enfoque erudito que uno tiene de la Biblia no le permite concluir, sobre la base de pruebas, la existencia de errores en las Escrituras. No es difícil ver cómo ese enfoque iría en contra del espíritu de una sólida epistemología evidencialista. Por otra parte, si se responde “no”, el interrogador puede suponer que se tiene un enfoque liberal de la Biblia y que se considera que no es fiable, o que se acepta una corriente de pensamiento, popular en la erudición contemporánea, que condena el proyecto de armonización cuando hay aparentes discrepancias en las Escrituras. Yo no me inclino por ninguno de esos dos extremos, y en este artículo expongo los matices de una aproximación a la Biblia que mantiene una visión elevada de las Escrituras, pero que no se aferra a la inerrancia tal y como se entiende tradicionalmente. Aunque técnicamente no me calificaría como inerrantista según las normas de la Declaración de Chicago, mi punto de vista se acerca mucho más al de la mayoría de los inerrantistas que al de la mayoría de los no inerrantistas. Es decir, tengo una visión elevada de las Escrituras y afirmo que las Escrituras, tanto el Antiguo como el Nuevo Testamento, son muy fiables.

Referencias

[1] Norman L. Geisler, Systematic Theology, Volume One: Introduction, Bible (Minneapolis, MN: Bethany House Publishers, 2002), 264–265.

[2] Para un debate sobre cómo se evalúan los datos anómalos en la ciencia, véase “The Role of Anomalous Data in Knowledge Acquisition: A Theoretical Framework and Implications for Science Instruction,” de Clark A. Chinn and William F. Brewer, Review of Educational Research 63, no. 1 (Spring, 1993), 1-49, y “Scientists’ Responses to Anomalous Data: Evidence from Psychology, History, and Philosophy of Science” de William F. Brewer and Clark A. Chinn, Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, Volume One: Contributed Papers (1994), 304-313.

[3] Bruce Manning Metzger, United Bible Societies, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Second Edition a Companion Volume to the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament (4th Rev. Ed.) (London; New York: United Bible Societies, 1994), 154.

[4] Michael Licona, Why Are There Differences in the Gospels? (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[5] Lydia McGrew, The Mirror or the Mask: Liberating the Gospels from Literary Devices (Tampa, FL: Deward Publishing Company, Ltd, 2019).

[6] Ibid., 53-54.

[7] Jerry Fodor y Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, What Darwin Got Wrong (London: Profile Books, 2011), kindle.

[8] Matthew Wilkins, “Matthew,” en The Holman Apologetics Commentary on the Bible — The Gospels and Acts, ed. Jeremy Royal Howard (Nashville, TN: Holman Reference, 2013), 99.

[9] Lydia McGrew, The Mirror or the Mask: Liberating the Gospels from Literary Devices (Tampa, FL: Deward Publishing Company, Ltd, 2019), 379-380.

[10] Ibid., 380.

[11] Craig L. Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of John’s Gospel (England: Apollos, 2001), 175.

[12] Steve Hays, “Projecting Contradictions, Triablogue, January 11, 2018, http://triablogue.blogspot.com/2018/01/projecting-contradictions.html

[13] Lydia McGrew, The Mirror or the Mask: Liberating the Gospels from Literary Devices (Tampa, FL: Deward Publishing Company, Ltd, 2019), 391.

[14] Thomas Rawson Birks, Horae Evangelicae, or The Internal Evidence of the Gospel History (London: Seeleys, 1852). Véase también Lydia McGrew, The Mirror or the Mask: Liberating the Gospels from Literary Devices (Tampa, FL: Deward Publishing Company, Ltd, 2019), 316–321.

[15] Tim McGrew y Lydia McGrew, “The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth”, en The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology, 1st Edition, ed. William Lane Craig and J.P. Moreland (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), kindle.

[16] Thomas Starkie, A Practical Treatise of the Law of Evidence, and Digest of Proofs, in Civil and Criminal Proceedings, Volume 1 (J & W.T. Clarke, 1833), 488-489.

Recursos recomendados en Español:

Robándole a Dios (tapa blanda), (Guía de estudio para el profesor) y (Guía de estudio del estudiante) por el Dr. Frank Turek

Por qué no tengo suficiente fe para ser un ateo (serie de DVD completa), (Manual de trabajo del profesor) y (Manual del estudiante) del Dr. Frank Turek

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

El Dr. Jonathan McLatchie es un escritor cristiano, orador internacional y debatiente. Tiene una licenciatura (con honores) en biología forense, un máster (M.Res) en biología evolutiva, un segundo máster en biociencia médica y molecular, y un doctorado en biología evolutiva. En la actualidad, es profesor adjunto de biología en el Sattler College de Boston (Massachusetts). El Dr. McLatchie colabora en varios sitios web de apologética y es el fundador de Apologetics Academy (Apologetics-Academy.org), un ministerio que trata de equipar y formar a los cristianos para que defiendan la fe de forma persuasiva mediante seminarios web regulares, así como ayudar a los cristianos que se enfrentan a las dudas. El Dr. McLatchie ha participado en más de treinta debates moderados en todo el mundo con representantes del ateísmo, el islam y otras perspectivas alternativas de cosmovisión. Ha dado conferencias a nivel internacional en Europa, Norteamérica y Sudáfrica promoviendo una fe cristiana inteligente, reflexiva y basada en la evidencia.

Fuente del blog original: https://cutt.ly/6zxWCsO

Traducido por Elenita Romero

Editado por Jennifer Chavez