For decades our country has been mired by a decision that enshrined the sacrifice of human babies to the god of Moloch (also known as Molech). You might know this practice by its current moniker, abortion, but the practice is essentially the same. Sacrificing our children on the altar of prosperity is a tail as old as human civilization. Instead of molten hands the altar is often a Planned Parenthood operating table.

We have chosen, as a nation, to ignore the obvious humanity of the infant in utero and have embraced the lie that sex is a right but having children as a result is anathema. That is, unless you want the baby.

In 1973, possibly the worst decision in the history of the Supreme Court was handed down in Roe v. Wade. I do not mean worst in merely the moral sense, though it is that, but also the legal sense. Finding the right to an abortion in the constitution took mental and philosophical gymnastics that would make Simone Biles jealous.[1] If you don’t believe me, perhaps you would believe Ruth Bader Ginsberg, not exactly a bastion of conservatism, when she said of the decision in 1992, “Doctrinal limbs too quickly shaped… may prove unstable.”[2]

This decision enshrined the murder of innocent children and the racially motivated eugenics of Margaret Sanger,[3] the founder of Planned Parenthood. If there is a social justice issue worth fighting, it is this one. Abortion effects minority communities more than any other in our society, in fact, over 40% of all abortions since 1973 were people of color.[4]

For decades this decision has meant the belittling of pre-born life, the slaughter of millions of babies, and the attempted genocide of the African American people. It is, in my opinion, one of the most corrupt and heinous failings in our country’s history. The decision to abort has been called a “woman’s right to choose.” Representative Ilhan Omar tweeted that “the Republican party supports forcing women to give birth against their will,” on May 3rd 2022.

The euphemistic language is by design, sure a woman might give birth against her will (unless the sex was consensual), but the baby is killed against his/her will every time. Which is worse? Saying the reality engenders discomfort. In reality “women’s reproductive rights” is simply a cover for worship of self and a desire for prosperity by sacrificing a life on the altar of convenience. The ease of life was always the goal of sacrifice to Moloch, abundant harvests were promised as the babies were laid on the glowing hot hands of the idol. “Give us prosperity because we give you our first-born children” has turned to “give us prosperity as we suck my preborn child lifelessly from the womb.”[5] Life will be easier for everyone if this child does not exist. Interestingly enough, I notice the child never has a say.

When pro-abortion advocates feel they are losing ground they often use extreme examples like rape or incest to insist that abortion must be kept legal if only for these cases. Only 1% of abortion cases are because of rape and even fewer are because of incest[6]. This Red Herring has proven effective, but it should not be. When granted the exception, it becomes obvious that limiting abortion to only cases of rape and incest would never be acceptable. The goal of this objection is to get the pro-life advocate to admit that the baby is not a real baby. If you are willing to allow a pre-born child to be killed due to a crime, then what is the point of limiting the act to only those that are victims of a crime. A life is a life is it not? In this argument they concede the point, not the other way around. However, murdering an innocent because he/she reminds you of a horrific crime you suffered is not moral. Committing a second evil does not negate the first evil committed. But most pro-lifers are willing to grant the exception. Why? It is not because they believe the personhood changes based on the condition of conception, but because when faced with the prospect that such a compromise might save 99% of babies that would otherwise be killed we say this, “It is not perfect, but it is a start.”

Other objections are similarly shallow. “Why force a woman who already has children to carry another child and make her life harder?” Perhaps because murder is never an excuse to make life easier, and then we pretend like adoption is not an option. Or, “wouldn’t it be better to have never been born than for a child to be born in abject poverty?” This is assuming the child will never amount to anything and, logically, we might as well exterminate all drug addicts and homeless people then because… wouldn’t it be better for them in the long run to simply be dead? All of these are Red Herrings, and houses of cars that easily crumble under slight scrutiny, but they are not meant to stand, they are meant to obfuscate by putting the pro-life person on the defense having to explain the position. And we often fall for it.

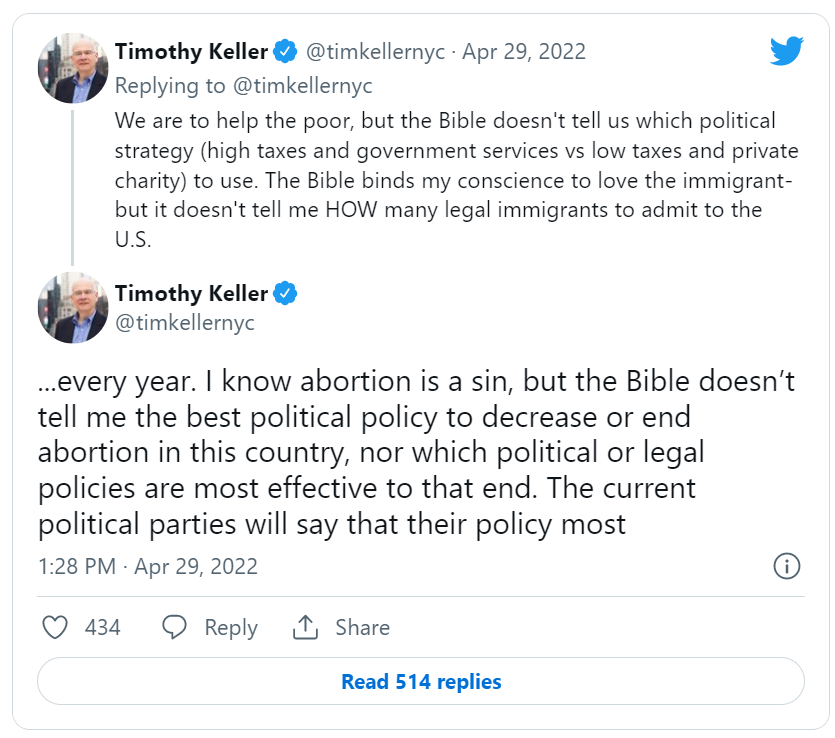

For many years overturning Roe v. Wade seemed like a political pipe dream. Something always talked about but never coming to fruition. Recently, notable theologian and pastor Tim Keller exemplified this thought with a twitter thread that seemed to indicate such a position:

While I disagree with Keller on many of his points here, I believe his position is one that took into account the pipe dream that was Roe v. Wade being overturned.

But now, all of that has changed. An unprecedented leak of a drafted Supreme Court decision to Politico[7] has forced many to recognize the pipe dream might become reality. But what does the accomplishment of this pipe dream do?

Well, contrary to popular belief on the left, the decision would not make abortion illegal on a federal level. Though, to be honest, I wish it did. All it will do is remove abortion as a “right” enumerated by the constitution under the guise of privacy. This would send the decision on whether to make abortion legal or not to individual states. All in all, it would only make it a little harder to get an abortion. Some states would maintain their laws while others would make abortion illegal. States already have the purview to put limitations on abortion after the first trimester.

However, this is a necessary first step in ending the idolatry of self and sex without consequences in our society. But, when the god of Moloch is challenge, his worshippers fight back. Death threats are sure to make their way to the Supreme Court in an attempt to dissuade the justices from maintaining their ruling. Let us hope that threat is where it stops. Regardless, the clear objective of the leak is to effect the decision of the courts in more than one way.

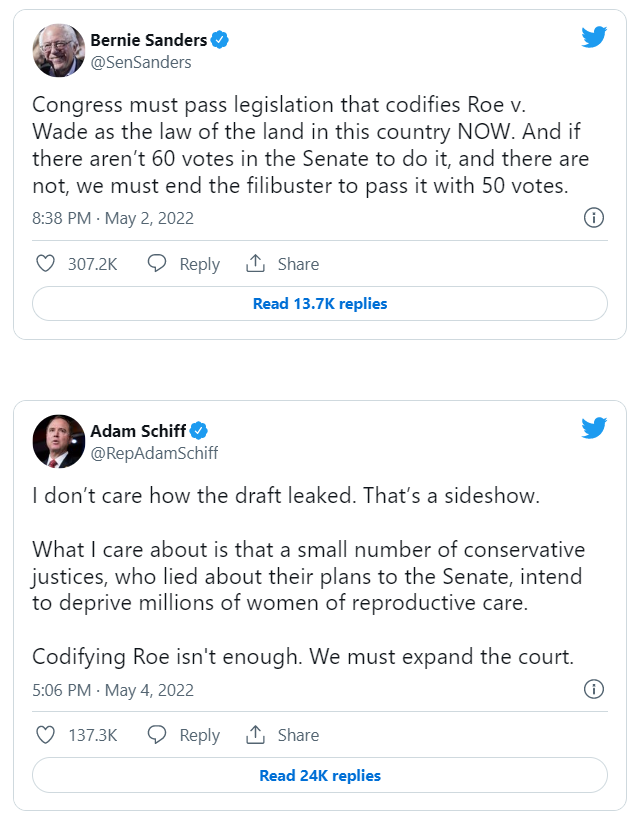

Clearly, this leak is an effort to pressure the House and Senate to do something the left has wanted them to do for some time now: end the filibuster, and pack the supreme court and codify Roe as law. This leak makes that desire more urgent and puts pressure on middle of the road Democrats like Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema to toe the party line and get the deal done. This is a delicate time in our nation’s history, and, in particular, our Republic. As of this writing members of congress are already setting the stage:

We would be mistaken, as believers, to think that this is a death knell to the abhorrent practice of abortion even if the decision comes out as the leak indicates it will. Abortion will still be practiced in many states and that, unfortunately, will not change.

While abortion has been made into a political and human rights issue (and it is), it is so much more than that to the Christian. While abortion is a clear evil in our society, and in culture at large, it is representative of a larger issue in society – the worship of self.

Self-actualization, self-identity, self-care, self-improvement, self-indulgence. Self, self, self, self, self.

We are a me-oriented society and thus, the idea that a person cannot choose for herself whether or not to kill another human being to ease the burdens of life is anathema. This is not simply about a culture war, this is a war concerning the gospel. Our battle is not against flesh and blood but against the rulers of this day and the worshippers of Moloch will not relinquish their grip easily.[8]

Plenty of states will harden their hearts and continue to come down with extreme legislation allowing abortion up to and possibly after birth[9]. This is not the end of the war, it is only a battle.

If we view this issue as primarily political, we miss the forest for the trees. We ought to be engaged in politics (see: Separation of Church and State Deception), but we must not make politics an end unto themselves. This has always been and will always be about the gospel, about being salt and light! What we will see in the coming days will be tantamount to spiritual revolution for the ardent Molochites. We ought not wilt in the periphery but stand on the hill. The truth, and life, is on our side. Compromising on murder for the sake of peace is not progress, it is surrender.

The worshippers of Moloch did not go quietly in the night during Israel’s time and the 21st century version will not go quietly into the night either.

To be clear, not everyone who is pro-choice is serving Moloch, but make no mistake, for the passionate abortion-at-all-costs radicals this is more about worship than it is about supposed rights. But don’t take my word for it:

“The right to an abortion is sacred.” This is sacramental language. And this avenue of worship has taken many forms throughout history, from Moloch, to Baal, to Baphomet, to the cult of self, whatever the Enemy can offer as a counterfeit to the real worship of God almighty in a given culture he will. Different times, different cultures, same methodology. Why fix what isn’t broken? The schemes of the devil are simple yet effective.

The promise is alluring, the worship is self-gratifying, and the outrage is intoxicating. But the end, as always, is death and misery, but most do not even recognize they are participating in the worship of darkness. They think they are enlightened humanists and many do not believe in the spiritual at all and that is just the way the Enemy wants it. Not many would knowingly bend a knee to Satan but if he can get them to worship the created rather than the creator it is just as well.

So what do we do?

Pray – A lot.

Keep the five justices of the Supreme Court and, in particular, members of Congress in your prayers continuously. Specifically pray for Brett Kavanaugh, Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito to remain safe and pray for the hearts and minds of the dissenting justices to be softened. Pray also for safety in our nation. Pray for an opportunity for the gospel to be heard. Pray that pro-life people, such as myself, will stand for life but also for the care of each person in the name of Christ. Pray that pastors and theologians, such as Tim Keller and many others, with a wide reach will find confidence and courage. This could be an inflection point in our nation’s history, pray that it is not squandered.

Do not fight the lies of Satan with half-truths and do not give ground. Be courageous. The darkness always hates the light but its power is fraudulent and without substance.

And finally, stay heartened, faithful, and committed to the cause of Christ!

[1] https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=3681&context=mlr

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/21/us/ruth-bader-ginsburg-roe-v-wade.html

[3] https://www.frc.org/op-eds/margaret-sanger-racist-eugenicist-extraordinaire

[4] https://www.bostonherald.com/2022/01/28/franks-high-abortion-rate-strikes-blow-at-black-community/

[5] https://allthatsinteresting.com/moloch

[6]https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2019/05/24/rape-and-incest-account-few-abortions-so-why-all-attention/1211175001/

[7] https://www.politico.com/news/2022/05/02/supreme-court-abortion-draft-opinion-00029473

[8] Ephesians 6:12

[9] https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/31/politics/ralph-northam-third-trimester-abortion/index.html

Recommended resources related to the topic:

The Case for Christian Activism (MP3 Set), (DVD Set), and (mp4 Download Set) by Frank Turek

Legislating Morality: Is it Wise? Is it Legal? Is it Possible? by Frank Turek (Book)

Defending Absolutes in a Relativistic World (Mp3) by Frank Turek

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Josh Klein is a Pastor from Omaha, Nebraska with over a decade of ministry experience. He graduated with an MDiv from Sioux Falls Seminary and spends his spare time reading and engaging with current and past theological and cultural issues. He has been married for 12 years to Sharalee Klein and they have three young children.

Original blog post: https://bit.ly/3FvkIBd