Don’t Be; That’s Just the New Atheists Masking Their Faith Choice

In the November 2006 cover story of Wired magazine, Gary Wolf thoughtfully gave ear to some of atheism’s most aggressive voices and labeled the movement that they lead “New Atheism.” Envisioning a brave new world in which science and reason overcome religious myth and superstition, New Atheists labor to purvey a comprehensive worldview that explains who we are and how we got here (Darwinian evolution), diagnoses our most urgent ill (ancient superstitions about God), and, most importantly, prescribes a cure for that ill (eradication of religion).

In the same month that Wired reported on New Atheism, Time magazine artfully depicted the science and religion quandary with a combination double helixÆrosary on its cover. The title, “God vs. Science,” might have led a casual reader to expect a story about a theologian opposing science, but the article actually covered a debate between two scientists. Geneticist Francis Collins, director of the Human Genome Project, and biologist Richard Dawkins of Oxford University weighed in on Time’s questions about science, belief in God, and whether the two can peaceably coexist in an intellectually sound world-view. Collins said they can; Dawkins said absolutely not.

Recent battles over textbooks in America lend credence to the notion of science and religion as perennial foes, and ABC News, reporting on a survey of atheism among scientists, casually commented that “the clash between science and religion is as old as science itself,” as if that’s what everybody with any gray matter already knows. But historians of science reveal a different story, one that is more in line with the view of Dr. Collins.

In his course Science and Religion, Lawrence Principe, professor of the History of Science and Technology at Johns Hopkins University, meticulously untangles the historical accounts of events commonly bandied about as proof that religion suppresses science, such as the trials of Galileo and John Scopes. Principe teaches that, contrary to irreligionist lore, the two disciplines were generally viewed as complementary until a little more than a century ago.

Principe identifies two late-19th-century publications as the origin of the idea of warfare between science and religion: A History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science, written by skeptic scientist John William Draper in 1874, and A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom, published in 1896 by Andrew Dickson White, first president of Cornell University. It is noteworthy that both writers seemed to want the church to back off; Draper wrote at the request of a popular science publisher, and White in response to criticism that he had received for establishing Cornell as the first American university with no religious affiliation.

Principe reveals that the premise of both books—that science and religion have occupied separate camps throughout history, and that religion has always been the oppressor of science—is unfounded, calling Draper’s book “cranky,” “ahistorical,” and “one long, vitriolic, anti-Catholic diatribe,” while White’s is “scarcely better.” Still, he credits the two sub-scholarly works with crystallizing in the popular mind the image of ongoing, intractable warfare between science and religion. Today’s New Atheists echo and amplify their war cries.

Are We Talking Science or Faith?

Skeptics ardently defend their right to reject religious dogma and make up their own minds about ultimate reality. Certainly, atheists, scientific or not, are free to adopt whatever belief system they choose, but can they legitimately claim science as the basis for atheism? Put more simply, has science disproved God, as the irreligionists maintain?

A closer look at Richard Dawkins and Francis Collins sheds light on that question. The most significant difference between the two scientists is not that one believes in biblical creation and the other in Darwinian evolution. Both affirm Darwinism. The salient distinction is that Collins allows for the possibility of God, whereas Dawkins does not.

But it wasn’t always so. The fourth son of two freethinkers, Francis Collins, was homeschooled until age ten. His parents instilled in him a love for learning, but no faith, and the agnosticism of his youth gradually shifted into atheism as his education progressed. He was comfortable with it, discounting spiritual beliefs as outmoded superstition until he began to interact with seriously ill patients as a medical student. When one of them, a Christian, asked him what he believed, he faced a rationalist’s crisis. “It was a fair question,” he wrote in The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief. “I felt my face flush as I stammered out the words ïI’m not really sure.’” At that point, Collins realized that he had never seriously considered the evidence for and against belief.

Determined to practice authentic, what-are-the-facts science, Collins set out to investigate the rational basis for faith. Reluctantly, he found himself feeling “forced to admit the plausibility of the God hypothesis. Agnosticism, which had seemed like a safe second-place haven, now loomed like the great cop-out it often is. Faith in God now seemed more rational than disbelief.”

In contrast to Collins’s rational inquiry and personal struggle over the question of God, Richard Dawkins, the de facto spokesman for scientific atheism (think Madalyn Murray O’Hair with a Ph.D.), lays out his case for unbelief without struggle or reservation. In chapter four of The God Delusion, titled “Why There Almost Certainly Is No God,” Dawkins introduces his “Argument from Improbability,” and though the chapter waxes long, its reasoning distills to something like this:

- The universe we observe is highly complex.

2. Any creator of this complex universe would have to be even more complex than it.

3. It is too improbable that such a God exists; therefore, there almost certainly is no God.

The first two statements qualify as acceptable premises, but the conclusion that Dawkins reaches simply does not follow from them. This isn’t legitimate reasoning. It’s rationalization—that is, finding some plausible-sounding explanation for arriving at a conclusion that he has already chosen.

Dr. Dawkins is certainly free to choose to disbelieve, but his conclusion was not derived through scientific or rational means. Rather, it hints at an underlying personal, philosophical faith choice to disbelieve. Ernst Mayr, one of the twentieth century’s leading evolutionary biologists, made a similar observation when he analyzed reasons for disbelief among his Harvard colleagues. “We were all atheists. I found that there were two sources,” he said. One group “just couldn’t believe all that supernatural stuff.” The other “couldn’t believe that there could be a God with all this evil in the world. Most atheists combine the two,” he summarized candidly. “The combination makes it impossible to believe in God.”

Former atheist and biophysicist Alister McGrath concurs, noting that most of the unbelieving scientists he is acquainted with are atheists on grounds other than their science. “They bring those assumptions to their science rather than basing them on their science.” Dawkins’s rationalization, as well as the observations of McGrath and Mayr, reveal the choice to disbelieve for what it is—a personal, philosophical choice made apart from reason or scientific inquiry. I call it a “faith choice” because it involves choosing a foundational presupposition concerning a realm about which we have incomplete (but not insufficient) knowledge.

A Choice of Faith

Francis Collins’s conclusion, that the God hypothesis is not only plausible but compellingly supported by evidence, flatly controverts New Atheism’s premise that faith constitutes an irrational belief without evidence. It also reveals that the real conflict isn’t one of science versus God. It’s a conflict between those who allow and those who disallow the possible reality of God.

Polemicists will continue to clamor for converts to their side on the question of God because between the poles live thoughtful, educated people—not necessarily working scientists, but people who value science. Some believe in a supreme being called God, and others haven’t made up their minds. It is these theological moderates that New Atheism seeks to recruit with pithy epigrams such as “God vs. Science” and “My beliefs are based on science, but yours are based on faith.” What believers need is a calm, judicious counter-strategy when New Atheism advances under the guise of science, one that can transform verbal sparring into illuminating dialogue. Let me give you an example of what I mean.

My friend Dana has known Sam for decades. Over the years, Sam has peppered her with questions about her faith. Despite feeling intimidated—Sam is a highly respected leader in their community—she has answered as best she could and maintained their friendship. One evening over dinner in her home, Sam turned his questions on her teenagers, essentially asking them, “Do you really believe all that stuff and why?” Dana allowed them to speak for themselves for a while before intervening.

“Sam,” she started agreeably, “you and I have discussed this many times. I’ve told you what I believe and why, and you’ve told me all of your reasons for not believing.” Then she posed a question that she had never put to him before. “What if there really is a God, but you just don’t know about him? Are you willing to consider that possibility? Are you willing to ask him if he’s out there? Something like ïGod, I’m not even sure if you’re there, but if you are, would you show yourself to me?‘”

Dana let her question hang in the air. The teenagers likewise waited for Sam to break the silence. “No,” he finally said. “I’m not willing to do that.” And he hasn’t brought the subject up since.

Dana gently—but powerfully—pierced the facade of scientific skepticism with one question: Are you willing? It is not a question of scientific reasoning, but a question of choosing, of making a personal faith choice that, once made, establishes the starting point for one’s reasoning. Atheism isn’t founded on science or reason any more than theism is based on faith devoid of reason. The atheist, too, has made a faith choice. He has just chosen differently.

The Eternal Conflict

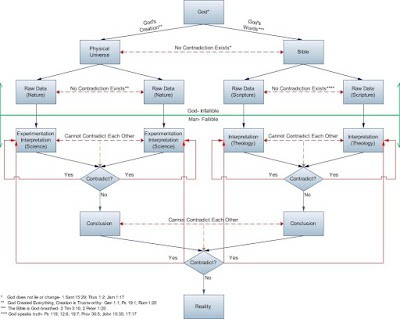

The “eternal conflict,” as it’s called, is not really between religion and science; after all, the two got along quite amicably before the twentieth century. No, as the following quotations indicate, the real quarrel has always been between those who believe that science and religion are at odds and those who do not.

“A legitimate conflict between science and religion cannot exist. Science without religion is lame; religion without science is blind.”

—Albert Einstein

“It is… Idle to pretend, as many do, that there is no contradiction between religion and science. Science contradicts religion as surely as Judaism contradicts Islam—they are absolutely and irresolvably conflicting views. Unless that is, science is obliged to change its fundamental nature.”

—Brian Appleyard

“Science and religion are two windows that people look through, trying to understand the big universe outside, trying to understand why we are here. The two windows give different views, but both look out at the same universe. Both views are one-sided, neither is complete. Both leave out the essential features of the real world. And both are worthy of respect.”

—Freeman Dyson

“Science can purify religion from error and superstition; religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world, a world in which both can flourish.”

—Pope John Paul II

“When religion was strong and science weak, men mistook magic for medicine; now, when science is strong and religion weak, men mistake medicine for magic.”

—Thomas Szasz

“Science is an effort to understand creation. Biblical religion involves our relation to the Creator. Since we can learn about the Creator from his creation, religion can learn from science.”

—PaulæH. Carr

“There is more religion in men’s science than there is science in their religion.”

—Henry David Thoreau

“Science makes major contributions to minor needs. Religion, however, small its successes, is at least at work on the things that matter most.”

—Oliver Wendell Holmes

Science as Religion

One needn’t speculate about whether science is a religion for Darwinists such as Richard Dawkins. In a 1997 essay published in The Humanist, Dawkins tackles this question directly, arguing that his onetime tendency to deny that science is a religion was a tactical error that he has since repudiated. Instead, he writes, scientists should “accept the charge gratefully and demand equal time for science in religious education classes.” The reason? Well, according to Dawkins, whereas science is a faith “based upon verifiable evidence,” religion “not only lacks evidence,” but “its independence from evidence is its pride and joy.” Thus, science is the only religion worth imparting to future generations.

Rather than delineate the evidence that makes science outclass “any of the mutually contradictory faiths and disappointingly recent traditions of the world’s religions,” however, Dawkins chooses instead to describe what science might someday do for a society that religion does today. Chiefly, this amounts to inspiring in people an awe for “the wonder and beauty” of the universe in the same way that God currently inspires awe in religious believers. Indeed, as far as Dawkins is concerned, “the merest glance through a microscope at the brain of an ant or through a telescope at a long-ago galaxy of a billion worlds is enough to render poky and parochial the very psalms of praise.”

But here is where the evolutionary biologist gets himself into trouble. Yes, science has given us access to astonishing truths about the hidden nature of the universe, and yes, all that it has definitively revealed is based on incontrovertible evidence. It is also true, however, that most religions in the world do not posit faith claims in opposition to such breathtaking factual findings. Rather, religion lacks evidence at precisely those points where science does as well.

The faith that is the “pride and joy” of religious believers is in an invisible God who created the world and still interacts with it. The faith of Darwinian scientists is in the power of evolution to create the world and then continue to adapt it. There is no conclusive evidence for either of these faith claims, which is why some have accused science of being a religion in the first place, as well as why Dawkins must hawk the replacement value of science instead of citing the “verifiable evidence” that makes science superior to conventional religion.

All this is to say that Dawkins is correct to concede that science is a religion for him, but wrong to contend that this particular religion accomplishes something that others do not. When it comes to the significant questions of life—Where did we come from? How did we get here? Why are we here? —Science’s answers prove to be as faith-based as those of even the most fundamentalist religious sect. That science might successfully fulfill the function of religion is thus hardly reason enough to warrant a switch.

Terrell Clemmons is a freelance writer and blogger on apologetics and matters of faith.

This article was originally published at salvomag.com: http://bit.ly/2J9O9vV