Richard Carrier is an ancient historian who has risen to prominence as the lead advocate of Jesus Mythicism, a school of thought that entertains the idea that Jesus of Nazareth may never have existed at all. While Mythicism occupies only the fringes of the scholarly guild, it has gained much better traction on the internet, where poor scholarship can be widely disseminated unchecked. In 2014, Richard Carrier published the first academic defense of Mythicism through Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd., an academic publisher.[1] Since this volume represents the first scholarly peer-reviewed publication supporting the Mythicist position and is written by an author with a doctoral degree in ancient history, the contents of Carrier’s thesis are deserving of attention.

Carrier examines the extrabiblical evidence of Jesus’ historicity, as well as the sources we find in the New Testament – the gospels, Acts, and epistles. While there is much that could be discussed in regards to Carrier’s handling of these sources, for the purpose of the present paper I will focus primarily on Carrier’s interaction with the Pauline corpus, though – for reasons that will become clear – I will also remark on the book of Acts insofar as it helps to illuminate the proper interpretation of Paul’s letters.

Having rejected the gospels and Acts as reliable documents, Carrier maintains that the letters of Paul are the best sources that bear on the question of the historicity of Jesus. He, however, contends that the letters of Paul fail to unequivocally refer to Jesus as an historical person who walked on earth. Instead, argues Carrier, Paul viewed Jesus as a celestial being, inhabiting a spiritual realm in outer space, in which He was crucified by demons and subsequently resurrected. Carrier’s thesis is in fact not a new idea, but one which was originally proposed by Earl Doherty, to whom Carrier owes much of his material.[2]

I cannot help but point out an irony in Carrier’s advocacy of scholarship that to call fringe would be an understatement. In one of Carrier’s other books, Why I Am Not a Christian, Carrier writes concerning biological evolution, “The evidence that all present life evolved by a process of natural selection is strong and extensive. I won’t repeat the case here, for it is enough to point out that the scientific consensus on this is vast and certain, so if you deny it you’re only kicking against the goad of your own ignorance.”[3] One wonders whether this quote has any relevance to the debate over Mythicism. I could forego interaction with Carrier’s argumentation by noting that “the evidence that Jesus existed is strong and extensive. I won’t repeat the case here, for it is enough to point out that the scholarly consensus on this is vast and certain, so if you deny it you’re only kicking against the goad of your own ignorance.” Presumably, Carrier would – quite rightly – object that I need to interact with his arguments rather than simply make an appeal to scholarly consensus. This is somewhat of an inconsistency on Carrier’s part.

In this paper, I will be primarily interacting with Carrier’s book, On the Historicity of Jesus. However, I may on occasion also draw from other publications by Carrier, including his blog posts, which might serve to illuminate his views or where he may have anticipated some of the objections I raise here.

An Analysis of Carrier’s Exegesis of the Undisputed Pauline Corpus

If Carrier’s position is to withstand scrutiny, Carrier must plausibly interpret those texts in the Pauline corpus that appear to situate Jesus on earth. There are in fact quite a number of details provided by the seven undisputed letters of Paul that give the strong appearance of representing Jesus as having lived on earth. Paul tells us that Jesus was born of the seed of David (Rom 1:3); that He was born of a woman, born under the law (Gal 4:4); that He delivered teachings about divorce (1 Cor 7:10); that He was betrayed (1 Cor 11:23); that He had a last supper (1 Cor 11:23-26); that He had brothers (Gal 1:19; 1 Cor 9:5); that He had twelve disciples (1 Cor 15:5); that He was crucified by the rulers of this age (1 Cor 2:8); and that He was killed by the Jews (1 Thes 2:13-16), and that He was buried. In this section, I will interact with Carrier’s exegesis of several of those texts listed above. I will not discuss Paul’s reference to “Christ Jesus, who in his testimony before Pontius Pilate made the good confession,” (1 Tim 6:13), since the authorship of the Pastorals is in scholarly dispute (and space does not permit me to do justice to the relevant literature), though I think a formidable case can be made for Pauline authorship of the Pastoral letters and indeed for all thirteen of Paul’s letters. I agree with Carrier, though for different reasons, that “There is a great deal wrong with how a ‘consensus’ has been reached on the dates and authorship of all these Christian materials, and the conclusions usually cited as established tend to be far more questionable than most scholars let on…I think there is a lot of work here that needs to be properly redone in NT studies, and I’m not alone in thinking that.”[4] I will also not discuss Paul’s reference to Jesus’ teachings on divorce or to the twelve, since I believe those can be interpreted in a manner that is consistent with Carrier’s thesis. The other texts listed above, however, are significant challenges to Carrier’s thesis, and it is to those that I now turn my attention.

Christ of the Seed of David (Rom 1:3): In the prologue of his letter to the Romans, Paul writes, “Paul, a servant of Christ Jesus, called to be an apostle, set apart for the gospel of God, which he promised beforehand through his prophets in the holy Scriptures, concerning his Son, who was born (γενομένου) of the seed (σπέρματος) of David according to the flesh,” (Rom 1:1-3). Carrier observes that, although the verb Paul uses here, γίνομαι, is used of birth by other authors, it is not the word that Paul customarily uses for birth, which is γεννάω (c.f. Rom 9:11; Gal 4:23,29).[5] Carrier argues that γίνομαι is used of God’s manufacture of Adam’s body from clay, and God’s manufacture of our glorified bodies in heaven. Thus, Carrier argues, this is a very odd word for Paul to use if he means to indicate that Jesus was born. Carrier’s proposed interpretation of Romans 1:3 is that God manufactured Jesus out of sperm that was obtained from David’s belly, an event that Carrier suggests took place in outer space.

Carrier has in mind here the Septuagint translation of Genesis 2:7, in which the word ἐγένετο (the aorist indicative form of γίνομαι) appears, describing the man as becoming a living creature. However, the word that is used here to describe the moment of divine manufacture is not ἐγένετο, but rather ἔπλασεν (the third person aorist indicative of the verb πλάσσω). The word ἐγένετο, rather, is used in this context to describe the change of state from non-living to living. Thus, it is not precisely correct to say that ἐγένετο refers to divine manufacture. Paul himself in fact alludes to this text (1 Cor 15:45). While Carrier asserts that Paul does not use γίνομαι to refer to a human birth, this only begs the question, since he must assume that Romans 1:3 and also Galatians 4:4 (which says that Jesus was born – γενόμενον – of a woman and born under the law) are not using the verb in this sense, which is the very question he is attempting to address. Furthermore, according to Liddell and Scott’s Intermediate Greek Lexicon, the verb γίνομαι, in the context of persons, means “to be born.”[6] We can independently verify this to be the case by analysing instances where this verb is used in the Septuagint, in order to discern how the word is used in relation to persons. Genesis 21:3 says, “Abraham called the name of his son who was born to him, whom Sarah bore him, Isaac.” In the Greek Septuagint, the Hebrew word נּֽוֹלַד־ (“was born”) is translated γενομένου. Another example is Genesis 46:27: “And the sons of Joseph, who were born to him in Egypt, were two.” Again, the Greek Septuagint renders this as γενομένου. Finally, consider Genesis 48:5: “And now your two sons, who were born to you in the land of Egypt before I came to you in Egypt, are mine; Ephraim and Manasseh shall be mine, as Reuben and Simeon are.” Here once again, the Greek Septuagint uses the word γενομένου.

Carrier points out that Paul also uses another verb, γεννάω, to refer to being born. One instance is Romans 9:11: “though they were not yet born (γεννηθέντων) and had done nothing either good or bad—in order that God’s purpose of election might continue, not because of works but because of him who calls.” The other instance is Galatians 4:23,29: “But the son of the slave was born (γεγέννηται) according to the flesh, while the son of the free woman was born through promise… But just as at that time he who was born (γεννηθεὶς) according to the flesh persecuted him who was born according to the Spirit, so also it is now.” While it may be granted that Paul uses the verb γεννάω to refer to being born, this entails nothing more than that Paul was willing to use synonyms for a word.

Another relevant question is how Paul himself uses the word σπέρματος (usually translated as “seed” or “offspring”) elsewhere. Paul writes, “I ask, then, has God rejected his people? By no means! For I myself am an Israelite, a descendant (σπέρματος) of Abraham, a member of the tribe of Benjamin,” (Rom 11:1). Here, Paul uses the exact same word for descendant as he used in Romans 1:3 to describe Jesus as being a descendent of David. If Paul – as he presumably did – believed that his descendance from Abraham entailed that he himself existed on earth, then it stands to reason that he also believed that Jesus existed on earth by virtue of His descendance from David.

To wrap up my analysis of this text, I will note that it is very clear from the dead sea scrolls that there was an expectation of a Davidic Messiah, and, moreover, this is likewise very evident from the Hebrew Bible as well. Therefore, the interpretation that Paul intends to express that Christ was born of the line of David is much more plausible than Carrier’s thesis that it refers to divine manufacture.

Born of a Woman (Gal 4:4): In Galatians 4:4, Paul writes, “But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born (γενόμενον) of woman, born under the law.” Carrier connects this verse to Galatians 4:24, where Paul writes, “Now this may be interpreted allegorically: these women are two covenants. One is from Mount Sinai, bearing children for slavery; she is Hagar.” Thus, Carrier wants to say that Galatians 4:4 is really only saying that Jesus was born of a covenant, not of a literal woman. This, however, is a very odd interpretation, since Paul only introduces the allegory in Galatians 4:21 — 17 verses after Galatians 4:4. In Galatians 4:24, Paul is only indicating that he is about to show an allegorical understanding of the narrative he has just alluded to in Genesis, concerning the births of Ishmael and Isaac. Indeed, the whole point of the allegorical interpretation of the two women is to show the true significance of Jesus’ birth given that Jesus traces his lineage back to Isaac, the child born through trust in God’s promise, and who who was born of the free woman Sarah (Gal 4:23).

But there is an even more damning objection to Carrier’s thesis here. That is, if Carrier’s theory about Galatians 4:4 is correct, then the allegorical interpretation makes sense only if we translate γενόμενον as “born” rather than “manufactured”. Therefore, if Carrier is correct here in his interpretation, he has himself refuted his own response to Romans 1:3, discussed above, that γενόμενον should not be used to refer to being born.

James the brother of the Lord (Gal 1:19): Paul claims personal acquaintance with an individual he refers to as “James the Lord’s brother” (Gal 1:19). Bart Ehrman cites this text as a persuasive piece of evidence for the historicity of Jesus.[7] Carrier observes that “Paul can use the phrase ‘brother of the Lord’ to mean Christian, since all Christians were brothers of the Lord.”[8] An example of this is Paul’s description of Jesus as “the firstborn among many brothers” (Rom 8:29). In response to this, Ehrman has pointed out that the phrase “the Lord’s brother” is used in Galatians 1:19 to distinguish James from Peter, who was not the brother of Jesus.[9] However, Carrier addresses this by pointing out that “the only two times [Paul] uses the full phrase ‘brother of the Lord’ (instead of its periphrasis ‘brother’), he needs to draw a distinction between apostolic and non-apostolic Christians.”[10] Thus, Carrier argues that James was not himself an apostle, and Paul uses the expression “the Lord’s brother” so as to distinguish him as a non-apostolic Christian, in contradistinction to Peter. However, this argument is problematic since it seems unlikely that Paul is implying – as would be required on Carrier’s interpretation – that he saw no other Christian, or even no-one of importance, in Jerusalem besides Peter and James. Ernest De Witt Burton concludes that “the phrase must probably be taken as stating an exception to the whole of the preceding assertion, and as implying that James was an apostle.”[11] Moreover, if Paul simply meant spiritual brother, one might expect him to instead write, ἕτερον δὲ τῶν ἀποστόλων οὐκ εἶδον, εἰ μὴ Ἰάκωβον τὸν ἀδελφὸν ἡμῶν (“I saw none of the other apostles, except James our brother”). Indeed, Peter refers to ἡμῶν ἀδελφὸς Παῦλος (“our brother Paul”) (2 Pet 3:15), so this would be a natural way of speaking of spiritual brotherhood.

Interestingly, Carrier also maintains that “only apostles ‘saw the Lord’, as that is what it was to be an apostle: to be one whom the Lord chose to reveal himself.”[12] But this statement appears to conflict with Carrier’s thesis that James was not an apostle, since Paul indicates that Jesus “appeared to James” (1 Cor 15:7). That this text is referring to the same James who is described in Galatians 1:19 is very likely, especially if, as suggested by many scholars, Paul received this creedal tradition upon his visit to Jerusalem some three years after his conversion, where he met with Peter and James (the very individuals specifically named in the creed) (Gal 1:18-19). Acts indicates that Peter and James were both prominent leaders in the Jerusalem church, and so they are natural for Paul to mention specifically by name. For Carrier to suggest that the individuals named James in Galatians 1:19 and 1 Corinthians 15:7 are different persons is special pleading involving pure speculation to save his theory. The clustering of the names Cephas and James in those two texts also suggests that the same two individuals are in view.

Paul also refers to “the brothers of the Lord” in the context of asking, “Do we not have the right to take along a believing wife, as do the other apostles and the brothers of the Lord and Cephas?” (1 Cor 9:5). Carrier insists that these are no more than cultic brothers of the Lord, as are all baptized Christians (c.f. Rom 8:29). A more natural way for Paul to say this, however, would be, instead of οἱ ἀδελφοὶ τοῦ κυρίου καὶ Κηφᾶς, to write Κηφᾶς καὶ άλλοι ἀδελφοὶ τοῦ κυρίου (“Cephas and the other brothers of the Lord”, since Cephas would be a brother of the Lord also, albeit an apostolic one).

The way it is worded in 1 Corinthians 9:5 suggests that the expression “the brothers of the Lord” refers to specific individuals who have taken for themselves a believing wife, just as the name Cephas refers to a certain individual.

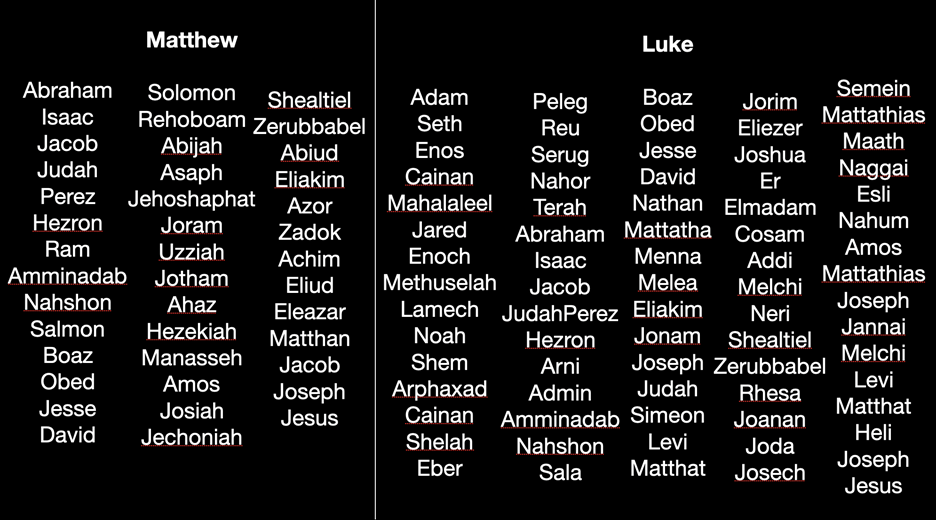

The fact that there exists independent evidence that Jesus had a brother called James also raises the prior probability that the allusion to “James the Lord’s brother” (Gal 1:19) is a reference to biological kinship. Mark reports people in a synagogue in Nazareth saying, “Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon? And are not his sisters here with us?” (Mk 6:3; c.f. Mt 13:55). Mark also reports that one of the women who visited Jesus’ tomb on the first day of the week was “Mary the mother of James the younger and of Joses,” (Mk 15:40). That this was Jesus’ mother is supported by the fact that Mark 6:3 reports that Jesus had brothers called James and Joses, likely mentioned in Mark 15:40 for their prominence in the early church. Matthew also indicates that Jesus had a brother called Joseph (Mt 13:55) – who presumably had inherited his father’s name – and Matthew’s account of the visit to the tomb of Jesus indicates that one of the women was “Mary the mother of James and Joseph” (Mt 27:56). Thus, if Paul was identifying some other prominent Christian as “the brother of the Lord” (Gal 1:19), he would probably have taken pains to distinguish Him from this other James, the Lord’s biological brother. Though Carrier might reply that the gospel authors used Paul’s letters as a source and misunderstood his meaning in Galatians 1:19, this is unlikely, since the gospel authors appear to be well informed regarding the presence and identity of those women at the tomb on Easter morning, for reasons that I have documented elsewhere.[13]

The Rulers of This Age (1 Cor 2:7-8): Another text that Carrier must deal with is 1 Corinthians 2:7-8: “But we impart a secret and hidden wisdom of God, which God decreed before the ages for our glory. None of the rulers of this age understood this, for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory.” At face value, this text certainly appears to indicate that Jesus was crucified on earth by the rulers and authorities of His day. Carrier argues that the “rulers” (ἀρχόντων – the genitive plural form of ἄρχων) here are demonic and spiritual forces rather than human authorities. In support of this, he argues, following Earl Doherty, that 1 Corinthians 2:8 “looks like a direct paraphrase of an early version of the Ascension of Isaiah, wherein Jesus is also the ‘Lord of Glory’, his descent and divine plan is also ‘hidden’ and the ‘rulers of this world’ are indeed the ones who crucify him, in ignorance of that hidden plan (see the Ascension of Isaiah 9.15; 9.32; 10.12,15). It even has an angel predict his resurrection on the third day (9.16), and the Latin/Slavonic contains a verse (in 11.34) that Paul actually cites as scripture, in the very same place (1 Cor. 2.9).”[14] However, that Paul is textually dependent upon the Ascension of Isaiah seems very unlikely, given that scholarly estimates of the date of the Ascension of Isaiah generally place it in the early second century (though estimates range between the late first century and the early third century). If there is any dependence, it is more likely that the Ascension is dependent on Paul, not the other way round.

Carrier claims that “The earliest version in fact was probably composed around the very same time as the earliest canonical Gospels were being written.”[15] However, Carrier offers no argument in support of this contention. Furthermore, no version of the Ascension of Isaiah indicates that Jesus was crucified by demons in the firmament. Maurice Casey, responding to Earl Doherty (from whom Carrier derives this argument) notes that “the devil is held responsible for an evil event. Crucifixions, however, took place on earth, as everyone knew, and there is nothing positive in this (or any other!) text to justify moving the crucifixion of Jesus up there. The subject of ‘will lay their hands upon him and hang him upon a tree (9.14) is obviously people who were there at the time, the conventional story, which had been well known for centuries when this document was being compiled. There is no excuse for Doherty to invent the idea that this was really ‘Satan and his evil angels’ crucifying Jesus up there in the heavens.”[16] Indeed, the Latin 2 version and the Slavonic version state that Jesus was on earth in human form. Starting when Jesus reaches the fifth heaven, Jesus takes the form of the inhabitants of each realm to which he descends. Since Jesus becomes like Isaiah’s form, it is entailed that Jesus takes on a human form and thus he descended down to the earth. Indeed, the Latin 2 and Slavonic versions explicitly state, “And I saw one like a son of man, and he dwelt with men in the world, and they did not recognize him” (11:1). Thus, the Ascension of Isaiah teaches that Jesus did come to earth. Moreover, that Jesus was not crucified by spiritual legions is further supported by the fact that Jesus does not even give a password to the “angels of the air,” because they were “plundering and doing violence to one another,” (Ascension of Isaiah 10:31).

Returning to 1 Corinthians 2:7-8, is Carrier’s interpretation of the rulers of this age plausible? The same word, ἄρχοντες (the nominative plural form), is used in Romans 13:3 to refer to human rulers, so the word ἄρχοντες certainly can refer to human rulers. It is therefore appropriate to evaluate from the context of 1 Corinthians 2:7-8 whether the word there refers to spiritual forces or human authorities, a question that I will take up momentarily.

What about the word αἰών, translated “age” in 1 Corinthians 2:8? Can that word be used in a plain and temporal sense? Absolutely, it can. Indeed, Paul uses the word that way himself in the preceding chapter: “Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age?” (1 Cor 1:20). He also writes in the proceeding chapter, “Let no one deceive himself. If anyone among you thinks that he is wise in this age, let him become a fool that he may become wise,” (1 Cor 3:18).

Now, what does the context of 1 Corinthians 2:7-8 reveal about the proper identification of the rulers of this age? Carrier correctly observes that there are parallel texts where the rulers are identified as the ones in heaven (Eph 3:9; 6:12). The point here, however, as we shall see, is the difference in context between the texts in 1 Corinthians and Ephesians. Paul, moreover, always uses specific modifying words when he is speaking about spiritual forces.

In any case, let us return to the specific context of 1 Corinthians 2. Paul writes, “Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world?” (1 Cor 1:20). The one who is wise, the scribe, and the debater are clearly human individuals. Paul, moreover, refers to human strength (1:25); “a human perspective,” and things that are “foolish” and “weak” (1:27), “despised in the world” and insignificant (1:28), and to “human wisdom” (2:13). He furthermore adds that his desire is that the Corinthian faith “not rest in the wisdom of men but in the power of God” (2:5), and that, though he imparted wisdom, it was “not a wisdom of this age or of the rulers of this age, who are doomed to pass away,” (2:6). It is in this context that we arrive at 2:8: “None of the rulers of this age understood this, for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory.” The text continues, “What no eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor the heart of man imagined, what God has prepared for those who love him” (v. 9). Paul goes on to write, “For who knows a person’s thoughts except the spirit of that person, which is in him? So also no one comprehends the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God,” (v. 11) Paul’s primary referent appears to be humans the whole way through, not demonic forces. What Paul writes next supports this case yet further: “Now we have received not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit who is from God, that we might understand the things freely given us by God. And we impart this in words not taught by human wisdom but taught by the Spirit, interpreting spiritual truths to those who are spiritual. The natural person does not accept the things of the Spirit of God, for they are folly to him, and he is not able to understand them because they are spiritually discerned. The spiritual person judges all things, but is himself to be judged by no one. ‘For who has understood the mind of the Lord so as to instruct him?’ But we have the mind of Christ” (vv. 12-16, emphasis added).

Thus, while Carrier’s reading of this text is not entirely impossible, by far the more plausible interpretation of this text, it seems to me, is that the rulers being spoken of here are indeed primarily human rulers, not demonic or spiritual forces. However, even if it be conceded that the referent in this text is spiritual forces, this does not support Carrier’s thesis since apocalyptic Jews believed that demons acted through human agency. For example, in the book of Daniel, Gabriel tells Daniel, “The prince of the kingdom of Persia withstood me twenty-one days, but Michael, one of the chief princes, came to help me, for I was left there with the kings of Persia,” (Daniel 10:13).

On the Night He was Betrayed (1 Cor 11:23-26): Carrier notes, rightly, that the verb παραδίδωμι, often translated in 1 Corinthians 11:23 as “to betray”, can also mean “to hand over.” Indeed, this same verb is even used of Jesus “giving up” His spirit at the time of his death (Jn 19:30). While “to betray” is certainly within this verb’s semantical range, Carrier is correct that this is an interpretive translation, based on the gospel accounts, and that “on the night He was handed over” – a reading that is consistent with Carrier’s thesis – would be an equally permissible translation. It is, however, more likely than not that betrayal is what Paul had in mind. All three of the synoptic gospels use this same verb in reporting Judas’ betrayal of Jesus and in those texts the “handing over” has connotations of betrayal (Mt 10:4; Mk 14:11; Lk 24:7).

Of further relevance here is Paul’s statement, also in this same chapter, that Jesus “took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, ‘This is my body, which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’ In the same way also he took the cup, after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me,’” (1 Cor 11:23-25). Carrier maintains that the meal being spoken of here is not an actual event that took place on earth, but something entirely hallucinated by Paul.[17] In support of this, he points to Paul’s words that “I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you,” (1 Cor 11:23). Thus, Carrier argues, this is information He has received directly from Jesus, and not from the apostles. However, Alfred Plummer and Archibald Robertson note, “why assume a supernatural communication when a natural one was ready at hand? It would be easy for St Paul to learn everything from some of the Twelve. But what is important is, not the mode of the communication, but the source. In some way or other St Paul received this from Christ, and its authenticity cannot be gainsaid; but his adding ἀπὸ ταῦ Κυρίου is no guide as to the way in which he received it.”[18]

The Jews who killed the Lord Jesus (1 Thes 2:15): Paul writes, “For you, brothers, became imitators of the churches of God in Christ Jesus that are in Judea. For you suffered the same things from your own countrymen as they did from the Jews, who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and drove us out, and displease God and oppose all mankind by hindering us from speaking to the Gentiles that they might be saved—so as always to fill up the measure of their sins. But wrath has come upon them at last!” (1 Thes 2:14-16). Carrier argues that this text is an interpolation, and was not originally part of Paul’s letter. However, not a single sufficiently complete manuscript lacks this text, so the arguments for supposing this text to be an interpolation rest entirely on considerations besides textual critical ones. The reason why some scholars have viewed this text as a scribal interpolation is because, though the epistle was written around 51 A.D., the fall of Jerusalem (70 A.D.) appears to be in view, especially in verse 16b. However, David J. Williams points out that “there is nothing that compels us to identify this passage and, in particular, the second half of verse 16 with that disaster. An alternative suggestion (always assuming that the reference is to something past and not future) contends that Paul had in mind the series of disasters in A.D. 49 involving Jews, including a massacre in the temple (Josephus, War 2.224–227; Ant. 20.105–112) and their expulsion from Rome (Suetonuis, Claudius 25.4; cf. Acts 18:2 and see further, Williams, Acts, pp. 319f.). But in the context of this letter and in the light of 1:10 especially, it may be best to understand the reference as eschatological—the wrath is yet to come upon them. In this case, the aorist (past) tense would be functioning in the prophetic manner to express what is future.”[19] The grounds for presuming this text to be an interpolation, therefore, seem to be quite weak.

Christ was Buried (1 Cor 15:4): The final text I will deal with from the undisputed Pauline corpus is Paul’s reference to Jesus’ burial (1 Cor 15:4). Carrier maintains that the “same popular cosmology, the heavens, including the firmament, were not empty expanses but filled with all manner of things, including palaces and gardens, and it was possible to be buried there.”[20] He notes that “In this worldview, everything on earth was thought to be a mere imperfect copy of their truer forms in heaven, which were not abstract Platonic forms but actual physical objects in outer space.”[21] In support of his contention that in the ancient cosmology it was possible to be buried in the firmament, Carrier claims that “the Revelation of Moses says Adam was buried in Paradise, literally up in outer space, in the third heaven, complete with celestial linen and oils. Thus human corpses could be buried in the heavens.”[22] In a footnote, Carrier cites Revelation of Moses 32-41 (esp. 32.4, 37-40). However, in 1 Corinthians 15 Paul is drawing a comparison between what happened to Jesus and what will happen to other people in the day of the Lord. Jesus is described as “the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep,” (1 Cor 15:20). Indeed, Paul spills much ink in his letters defending the coming general resurrection of the dead in Christ. Paul points to Jesus as an example. In this text, Paul is saying that Jesus is the first of the faithful to die physically and to be resurrected in a transformed spiritual body. Since Jesus is the firstfruits of those who will be resurrected on earth, it seems most probable that, just like all of the other human bodies that were buried on earth, Paul is envisioning Jesus as having been buried on earth. Carrier thus has to engage in special pleading to make an exception in Jesus’ case. Paul’s argument here makes not one lick of sense unless he believed that Jesus had a real flesh and blood body that lived physically on earth.

The Relevance of the Book of Acts to Pauline Interpretation

If Luke-Acts represents the composition of an individual who was a travelling companion of the apostle Paul, then it would be quite odd if Luke and Paul were to have such strikingly different views of who Jesus was. Luke clearly perceived Jesus to have been a man who walked on earth. On Carrier’s thesis, this is particularly surprising given that Paul does not mention or differentiate himself from any alternative school which maintained that Jesus walked on earth. A demonstration of the personal acquaintance of Luke with Paul, therefore, provides confirmatory evidence that the traditional interpretation of Pauline Christology is essentially correct. There exist numerous lines of evidence for Luke being a travelling companion of Paul. Notably, there are the famous “we” passages, beginning in Acts 16, which are best understood as indicating the author’s presence in the scenes he narrates. Craig Keener observes that the “we” pronouns trail off when Paul travels through Philippi, only to reappear in Acts 20 when Paul passes once again through Philippi.[23] This is suggestive that the author had remained behind in Philippi and subsequently re-joined Paul when Paul returned through Philippi.

Luke demonstrates very specific and detailed local knowledge that points to his close familiarity with Paul’s travels. These are all items of information that would not have been general knowledge or easily accessible. I will provide a few examples here to give a flavour of the sort of evidence we are talking about, though other authors, such as Colin Hemer, have documented many more.[24] I will list a handful of instances of the titles of local officials that Luke so effortlessly gets right. Luke gets right the precise designation for the magistrates of the colony at Philippi as στρατηγοὶ (Acts 16:22), following the general term ἄρχοντας in verse 19. Luke also uses the correct term πολιτάρχας of the magistrates in Thessalonica (17:6). He also gets right the term Ἀρεοπαγίτης as the appropriate title for the member of the court in Areopagus (Acts 17:34). He also correctly identifies Gallio as proconsul, resident in Corinth (18:12), an allusion that allows us to date the events to the period of summer of 51 A.D. to the spring of 52 A.D., since that is when Gallio served as proconsul of Achaia. Luke, moreover, uses the correct title, γραμματεὺς, for the chief executive magistrate in Ephesus (19:35), found in inscriptions there. Furthermore, when Luke tells us of the riot in Ephesus, he indicates that the city clerk told the crowd that “There are proconsuls” (Acts 19:38). A proconsul is a Roman authority to whom one might take a complaint. Normally, there was only one. So, why does Luke so casually use the plural term (ἀνθύπατοί) here? It turns out that, just at that particular time, there was in fact two as a result of the assassination by poisoning, in the fall of 54 A.D., of the previous proconsul, Silanus (Tacitus’ Annals 13.1). This, again, is something that would be rather difficult to get right by fluke. Luke even uses the correct Athenian slang word that the Athenians use of Paul in 17:18, σπερμολόγος (literally, “seed picker”), as well as the term used of the court in 17:19 — Ἄρειον Πάγον, meaning “the hill of Ares”. Luke also gets right numerous points of geography, sea routes, and landmarks. For example, he is correct about a natural crossing between correctly named ports (Acts 13:4-5). He names the proper port, Perga, for a ship crossing from Cyprus (13:13). He names the proper port, Attalia, that returning travelers would use (14:25). Luke also correctly names the place of a sailor’s landmark, Samothrace (16:11). He also correctly implies that sea travel was the most convenient means of traveling from Berea to Athens (17:14-15). Furthermore, Colin Hemer notes that “Paul’s staying behind at Troas and travelling overland to rejoin the ship’s company at Assos is appropriate to local circumstances, where the ship had to negotiate an exposed coast and double Cape Lectum before reaching Assos,” (Acts 20:13-14).[25]

Luke even gets the implied location of the island of Cauda correct in Acts 27, despite Ptolemy and Pliny the Elder getting it wrong.[26] And so it goes on and on. Furthermore, numerous passages of Acts artlessly dovetail with Paul’s letters in a way that supports both the truth of Acts as well as the authenticity of the letters.[27] For example, the cause of Barnabas’ strong desire for Mark to accompany him and Paul (eventually leading to them splitting ways) (Acts 15:36-41) is illuminated by a casual reference by Paul to the fact that Barnabas and Mark were cousins (Col 4:10), a detail not supplied by Acts.

Carrier dedicates a chapter of his book to discussing the book of Acts[28], though his arguments in that chapter are extremely disappointing – possibly even more so than his handling of the Pauline corpus. Moreover, Carrier adopts an extremist and indefensible position, namely, that the narrative of the book of Acts is “certainly not what happened, even in outline.”[29] Space does not permit me to discuss all of this chapter’s many problems in detail, but I will offer a few examples.

Carrier complains that “In Acts’ history of the movement, from the moment the flock first goes public, in the very city of Jerusalem itself, at no point in the story (anywhere in all subsequent 27 chapters spanning three decades of history) do either the Romans or the Jews ever show any knowledge of there being a missing body. Nor do they ever take any action to investigate what could only be to them a crime of tomb robbery and desecration of the dead (both severe death penalty offenses), or worse.”[30] However, this is an argument from silence, which is an extremely weak form of argument in historical inquiry.[31] Just because a source makes no mention of an event, even when he might be expected to, it does not provide strong evidence disconfirming the event in question. For example, the first-century Jewish writers Josephus and Philo both fail to mention the expulsion of the Jews from Rome by Claudius, though it is mentioned by the Roman historian Suetonius in the second century (Claudius 25.4). There is only one brief mention of the event in any first-century source (Acts 18:2). Despite the silence of these authors, it is widely recognized by historians that this event took place.

A second complaint that Carrier has about Acts is the fact that “all the people associated with a historical Jesus…disappear from the historical record entirely.”[32] As examples, Carrier points out that Pontius Pilate, Joseph of Arimathea, Simon of Cyrene, and his sons, Martha, Lazarus, Nicodemus, and Mary Magdalene are not mentioned at all in the book of Acts. However, this is an argument from silence of the very weakest sort. The silence of the book of Acts on the fate of characters who are significant in the gospels does in no way impugn the historicity of Acts. The book of Acts is about the spread of early Christianity and about certain key apostles, particularly Peter and Paul. There is absolutely no reason whatever to expect Acts to mention every character with a role in the gospels.

Carrier also claims that Luke contradicts Paul’s letters. He writes, “For example, we know Paul ‘was unknown by face to the churches of Judea’ until many years after his conversion (as he explains in Gal. 1.22-23), and after his conversion, he went away to Arabia before returning to Damascus, and he didn’t go to Jerusalem for at least three years (as he explains in Gal. 1.15-18), whereas Acts 7-9 has him known to and interacting with the Jerusalem church continuously from the beginning, even before his conversion, and instead of going to Arabia immediately after his conversion, in Acts he goes immediately to Damascus and then back to Jerusalem just a few weeks later, and never spends a moment in Arabia. And yet we have the truth from Paul himself.”[33] However, a closer inspection of those texts reveals no contradiction at all. Luke tells us that “When many days had passed, the Jews plotted to kill him, but their plot became known to Saul. They were watching the gates day and night in order to kill him, but his disciples took him by night and let him down through an opening in the wall, lowering him in a basket,” (Acts 9:23-25). How long a period of time is denoted by “…many days…”? In 1 Kings 2:38-39, the phrase “many days” in Hebrew is immediately glossed as three years. But what about the trip to Arabia? Luke is silent on it, but does Luke contradict Paul’s claim that he went to Arabia? I would place Paul’s trip to Arabia within the “many days” of Acts 9:23. Paul also informs us that he “returned again to Damascus (Gal 1:17), so it is not surprising that his subsequent trip to Jerusalem is from Damascus. As for Paul being “still unknown in person to the churches of Judea that are in Christ” during his travels through Syria and Cilicia (Gal 1:22), this does not seem to me to be a great difficulty at all. Acts 8:1-3 indicates that Paul had been involved in persecuting the church in Jerusalem, to be distinguished from the whole region of Judea. Acts 8:1 in fact indicates that the believers in Jerusalem “were scattered throughout the regions of Judea and Samaria.” They no doubt would have told other believers with whom they came into contact of the persecution they had experienced under Saul of Tarsus, but it does not follow that the churches in Judea would generally have known him by sight, although they would doubtless have known him by reputation.

Carrier also claims various textual parallels that he argues “are too numerous to be believable history, and reflect the deliberate intentions of the author to create a narrative that served his purpose.”[34] However, even if textual parallels are close enough (and sufficiently improbable by coincidence) to be indicative of authorial intent, it is possible for an author to draw a parallel between real history and some other narrative, and deliberately word his account with the intent of drawing the reader’s mind to that text. The parallels Carrier draws, however, are generally unconvincing. For example, Carrier claims that “Luke makes Paul’s story parallel Christ’s.”[35] The parallels he draws attention to include that “both undertake peripatetic preaching journeys, culminating in a last long journey to Jerusalem, where each is arrested in connection with a disturbance in the temple’, then ‘each is acquitted by a Herodian monarch, as well as by Roman procurators’. Both are also plotted against by the Jews, and both are innocent of the charges brought against them. Both are interrogated by ‘the chief priests and the whole Sanhedrin’ (Acts 22.30; Lk. 22.66; cf. Mk 14.55; 15.1), and both know their death is foreordained and make predictions about what will happen afterward, shortly before their end (Lk. 21.5-28; Acts 20.2-38; cf. also 21.4).”[36] These coincidences are not at all sufficiently improbable to indicate authorial intent, in particular since Jesus and Paul both occupied the same socio-political setting.

Furthermore, Carrier subsequently goes on to note that “Paul does almost everything bigger than Jesus: his journeys encompass a much larger region of the world (practically the whole northeastern Mediterranean); he travels on and around a much larger sea (the Mediterranean rather than the Sea of Galilee); and though, like Jesus, on one of these journeys at sea he faces the peril of a storm yet is saved by faith, Paul’s occasion of peril actually results in the destruction of a ship. Likewise, Paul’s trial spans years instead of a single night, and unlike Jesus, veritable armies plot to assassinate Paul, and actual armies come to rescue him (Acts 23.20-24). While Jesus stirs up violence against himself by reading scripture in one synagogue (Lk. 4.16-30), Paul stirs up violence against himself by reading scripture in two synagogues (Acts 13.14-52 and 17.1-5). However, whereas Christ’s story ends with his gruesome death (which had a grand salvific purpose, which could not be claimed for Paul’s ultimate death, and which to end well had to be followed by a once-and-final resurrection, something that could also not be claimed for Paul), Paul’s story ends on a conspicuously opposite note: ‘and he abode two whole years in his own hired dwelling, and received all that went to him, preaching the kingdom of God, and teaching the things concerning the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness, none forbidding him’, something even Jesus could not accomplish when he was in Roman custody (Acts 28.30-31). Thus Paul out-does Jesus even in that.” It appears here that, according to Carrier’s historical methodology, similarities between Jesus’ and Paul’s life are to be taken as evidence against Acts’ historicity, and differences between Jesus’ and Paul’s life are also to be taken as evidence against Acts’ historicity. This is a classic ‘heads I win; tails you lose’ argument.

Carrier also argues for a late date of Acts, following Richard Pervo who dates Acts to the second century A.D.[37] The primary motivation for such a late date is the argument that Luke was dependent upon Josephus’ Antiquities (~93 or 94 A.D.). Craig Keener notes in response to this suggestion that “It would be difficult, however, for Luke to have made direct use of Josephus; Josephus’s Antiquities probably was issued about 93/94, and the copies of its twenty books would have been quite expensive and not readily available soon after their publication to nonelite persons.”[38] Furthermore, he adds, “In the final analysis, it is highly unlikely that Luke depends on Josephus. The strongest argument for dependence is Luke’s citation of Theudas and Judas. Yet it seems unlikely that Luke would have read Jos. Ant. 18–20, used barely any of it, and then gotten wrong the one point most likely drawn from it, if he was dependent at all. The other matters that he could have taken from Josephus were widely known. Josephus did not compose his reports of Theudas or Judas from thin air, and oral or written reports about these leaders would have been available to Luke as well as to Josephus. Josephus completed his Antiquities no earlier than 93 C.E., but Luke’s sometimes positive portrayal of Roman administrators probably would make less sense in the later years of Domitian’s reign.”[39]

Finally, Carrier claims that whereas “everywhere else, the speeches and sermons in Acts are conspicuously historicist; but when Paul is on trial, where in fact historicist details are even more relevant and would even more certainly come up, they are suddenly completely absent. That is very strange; which means, very improbable. The best explanation of this oddity is that Paul’s trial accounts were not wholesale Lukan fabrications but came from a different source than the speeches and sermons Luke added in elsewhere – a source that did not know about a historical Jesus.”[40] However, Paul’s allusion to “the name of Jesus of Nazareth” in His defense before Agrippa implies that Nazareth was Jesus’ hometown (Acts 26:9). The Greek is τὸ ὄνομα Ἰησοῦ τοῦ Ναζωραίου (literally, “the name of Jesus the Nazarene”). Carrier might respond to this by claiming that the Nazarenes may have been a cultic sect, and that it is not referring to the town of Nazareth in Galilee.[41] However, it is worthy of attention that the servant girl in Matthew 26:71 likewise uses the exact same expression, speaking of Peter: Οὗτος ἦν μετὰ Ἰησοῦ τοῦ Ναζωραίου (“this man was with Jesus the Nazarene”). But Matthew clearly believed that Jesus was raised in the town of Nazareth in Galilee (Mt 2:23; 21:11). Since the idea that Jesus was born in the town of Nazareth is found in all four gospels, including the independent birth narratives in Matthew and Luke, it is likely that this tradition goes back extremely early.

To summarize this section, there are good reasons to believe the author of Acts to have been a travelling companion of Paul, and Carrier fails to offer comparably good reasons for thinking he was not. If Paul was indeed a travelling companion of Paul, then it is quite surprising on Carrier’s thesis that Luke and Paul believed such starkly different things about Jesus – especially something as fundamental as whether Jesus lived on earth or was a celestial being who never actually walked the earth. Thus, the evidence for Luke being a travelling companion of Paul suggests that the traditional interpretation of Pauline Christology is the correct hermeneutical framework for understanding those texts previously discussed.

Conclusion

To conclude, the evidence from the Pauline corpus strongly indicates that the apostle Paul believed that Jesus was a real person who lived physically on earth. Paul was an apocalyptic Jew, and thus the beliefs of apocalyptic Jews must be taken as the interpretive framework for understanding Paul’s letters. Since Paul was personally acquainted with multiple first-hand eyewitnesses of Jesus’ life (including Jesus’ closest disciple Peter, and Jesus’ biological brother James), Paul’s testimony provides good reason to conclude that Jesus existed.

Footnotes

[1] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014).

[2] Earl Doherty, Jesus: Neither God Nor Man – The Case for a Mythical Jesus (Ottawa: Age of Reason Publications, 2009).

[3] Richard Carrier, Why I Am Not a Christian – Four Conclusive Reasons to Reject the Faith (California: Philosophy Press, 2009), 60.

[4] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 304.

[5] Ibid., 658. See also Richard Carrier, “The Cosmic Seed of David”, Richard Carrier Blogs, October 18, 2017. https://www.richardcarrier.info/archives/13387.

[6] Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford: Calerondon Press, 2019).

[7] Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist? The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth (California: HarperOne, 2012), 145-148.

[8] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 669.

[9] Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist? The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth (California: HarperOne, 2012), 145-148. See also Bart Ehrman, “Carrier and James the Brother of Jesus”, The Bart Ehrman Blog – The History and Literature of Early Christianity, November 5, 2016. https://ehrmanblog.org/carrier-and-james-the-brother-of-jesus/

[10] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 588-590. See also Richard Carrier, “Ehrman and James the Brother of the Lord”, Richard Carrier Blogs, November 6, 2016. https://www.richardcarrier.info/archives/11516.

[11] Ernest De Witt Burton, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1920), 60.

[12] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 137.

[13] Jonathan McLatchie, “The Resurrection of Jesus: The Evidential Contribution of Luke-Acts”, Jonathan McLatchie website, October 5, 2020, https://jonathanmclatchie.com/the-resurrection-of-jesus-the-evidential-contribution-of-luke-acts/

[14] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 64.

[15] Ibid., 53.

[16] Maurice Casey, Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicst Myths? (Biblical Studies) (London: T&T Clark, 2014), 262.

[17] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 642. See also Richard Carrier, “Historicity Big and Small: How Historians Try to Rescue Jesus”, Richard Carrier Blogs, April 25, 2018. https://www.richardcarrier.info/archives/13812.

[18] Alfred A. Plummer and Archibald T. Robertson, A critical and exegetical commentary on the First epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians (New York: T&T Clark, 1911), 242–243).

[19] David J. Williams, 1 and 2 Thessalonians (Michigan: Baker Books), 48–49.

[20] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 217.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid., 220.

[23] Craig Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary, Vol. 1 (Michigan: Baker Academic, 2012), 431.

[24] Colin Hemer, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History (Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1990).

[25] Ibid., 125.

[26] Ibid., 330-331. See also James Smith, The Voyage and Shipwreck of St. Paul: With Dissertations on the Life and Writings of St. Luke, and the Ships and Navigation of the Ancients, Fourth Edition, Revised and Corrected (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1880).

[27] Lydia McGrew, Hidden in Plain View: Undesigned Coincidences in the Gospels and Acts (Ohio: DeWard Publishing Company, 2017). See also William Paley, Horae Paulinae or, the Truth of the Scripture History of St. Paul Evinced (In The Works of William Paley, Vol. 2 [London; Oxford; Cambridge; Liverpool: Longman and Co., 1838].

[28] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), chapter 9.

[29] Ibid., 424.

[30] Ibid., 429.

[31] Timothy McGrew, “The Argument from Silence”, Acta Analytica 29, 215-228 (October 2013).

[32] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 431.

[33] Ibid., 423.

[34] Ibid., 424.

[35] Ibid., 425.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid., 308; Richard Pervo, Dating Acts: Between the Evangelists and the Apologist (California: Polebridge, 2006).

[38] Craig Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary, Vol. 1 (Michigan: Baker Academic, 2012), 394.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014), 437.

[41] Ibid., 562.

Recommended resources related to the topic:

Jesus, You and the Essentials of Christianity – Episode 14 Video DOWNLOAD by Frank Turek (DVD)

Early Evidence for the Resurrection by Dr. Gary Habermas (DVD), (Mp3) and (Mp4)

Cold Case Resurrection Set by J. Warner Wallace (books)

Cold-Case Christianity: A Homicide Detective Investigates the Claims of the Gospels by J. Warner Wallace (Book)

The New Testament: Too Embarrassing to Be False by Frank Turek (MP3) and (DVD)

Why We Know the New Testament Writers Told the Truth by Frank Turek (mp4 Download)

The Top Ten Reasons We Know the NT Writers Told the Truth mp3 by Frank Turek

Counter Culture Christian: Is the Bible True? by Frank Turek (Mp3), (Mp4), and (DVD)

Dr. Jonathan McLatchie is a Christian writer, international speaker, and debater. He holds a Bachelor’s degree (with Honors) in forensic biology, a Masters’s (M.Res) degree in evolutionary biology, a second Master’s degree in medical and molecular bioscience, and a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology. Currently, he is an assistant professor of biology at Sattler College in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. McLatchie is a contributor to various apologetics websites and is the founder of the Apologetics Academy (Apologetics-Academy.org), a ministry that seeks to equip and train Christians to persuasively defend the faith through regular online webinars, as well as assist Christians who are wrestling with doubts. Dr. McLatchie has participated in more than thirty moderated debates around the world with representatives of atheism, Islam, and other alternative worldview perspectives. He has spoken internationally in Europe, North America, and South Africa promoting an intelligent, reflective, and evidence-based Christian faith.

Original Blog Source: https://cutt.ly/1hbDO3h

Bethany is on the southeastern slopes of the Mount of Olives. We know Bethany was one of Jesus’ favorite places as it was the home of Mary, Martha, and Lazarus. The Book of Acts tells us that they returned from the Mount of Olives. Luke tells us the ascension happened in Bethany.

Bethany is on the southeastern slopes of the Mount of Olives. We know Bethany was one of Jesus’ favorite places as it was the home of Mary, Martha, and Lazarus. The Book of Acts tells us that they returned from the Mount of Olives. Luke tells us the ascension happened in Bethany.