I have been publishing a series of articles on how best to interpret the early chapters of Genesis and how science can illuminate biblical texts and guide our hermeneutics.

In this article, I will explore the text of the first chapter of Scripture, Genesis 1, with a view to determining whether this text commits to a young-Earth interpretation of origins or, at least, the extent to which the text tends to support such a view, if at all.

It is common for young-earth creationists to assume that if a young-earth interpretation of the text can be shown to be the most valuable or simplest hermeneutical approach, then this is the view one should prefer, and therefore the scientific evidence should be shoehorned into a young-earth mold. However, as I have argued in previous articles, this does not necessarily follow, since we have to deal not only with special revelation, but also with general revelation. In view of the independent considerations that justify the belief that Genesis is inspired Scripture and those that compel us to affirm an ancient earth and cosmos, interpretations that result in harmony between science and Scripture should be preferred over those that put them in conflict. Charles Hodge (1797-1878), a conservative 19th-century Presbyterian, put it this way [1] :

It is admitted, of course, that taking the [Genesis creation] account by itself, the most natural thing would be to understand the word [“day”] in its ordinary sense; but if that sense brings the Mosaic account into conflict with the facts, and another sense avoids that conflict, then it is obligatory to adopt that other sense….The Church has been forced more than once to modify her interpretation of the Bible to accommodate the discoveries of science. But this has been done without doing violence to the Scriptures or in any way undermining their authority.

As I have argued before, ad hoc auxiliary hypotheses regarding either science or Scripture can reasonably be invoked only if the overall evidence for Christianity is sufficient to support it. In my view, the evidence for Christianity, strong as it is, is insufficient to support the weight of a young-Earth interpretation of cosmic and geological history. However, I believe it is sufficient to support the weight of an old-Earth interpretation of Scripture (though I realize that a certain level of subjectivity is necessary in making this assessment). Therefore, if the text of Scripture compels one to subscribe to a young-Earth view, then the hypothesis that Scripture is wrong should be preferred to concluding that the Earth and cosmos are, in fact, young (i.e., on the order of thousands of years). However, before reaching such a conclusion, alternative interpretive approaches that do not entail a manifestly false implication should be fairly evaluated.

An important consideration in evaluating harmonizations, and one that is often overlooked, is that the evidentiary weight of a proposed error or contradiction in Scripture relates not so much to the probability of any one proposed harmonization, but rather to the disjunction of the probabilities associated with each candidate harmonization. To take a simplistic example, if one has four harmonizations that each have a 10% chance of being correct, then the evidentiary weight of the issue is significantly lower than if one had only one of them, since the disjunction of the relevant probabilities would be 40%. Thus, the text would be only slightly more erroneous than null (and inductive arguments for substantial reliability may tip the balance in favor of giving the author the benefit of the doubt). In reality, of course, the mathematics is rather more complicated than this, since one must take into account whether any of the harmonisations overlap or imply each other in such a way that the probabilities cannot be added to one another. This principle can be applied to our analysis of the text of Genesis 1 – the disjunction of the various interpretations that can be offered reduces the probative value of those texts’ case against the reliability of the text. Of course, if some of the disjuncts have a very low probability of being correct, then they will not be of much help.

If the biblical text were found to be in error, then the ramifications of that discovery would need to be explored. Admittedly, a demonstration of the falsity of inerrancy would constitute evidence against inspiration and in turn against Christianity, since there is admittedly a certain impulse toward inerrancy if a book is held to be divinely inspired in any significant sense, although I am not convinced that inspiration necessarily implies inerrancy, depending on which model of inspiration is adopted (perhaps a topic for a future article). However, since inerrancy is an “all or nothing” proposition, once a single error (and thus falsified inerrancy) has been admitted, the evidentiary weight against Christianity of subsequent demonstrations of similar types of errors is substantially reduced. Some of the proposed errors would be more consequential than others. Some errors (such as the long-life reports discussed in my previous article) would affect only the doctrine of inerrancy (as well as being epistemically relevant to the substantial reliability of particular biblical books), while others (such as the nonexistence of a robust historical Adam), being inextricably linked to other central propositions of Christianity, would be far more serious. Another factor that influences the epistemic consequence of scriptural errors is the source of those errors. For example, deliberate distortions of the facts have a far greater negative effect on both the doctrine that the book is inspired and the substantial reliability of the document than errors introduced in good faith.

Did God create a mature universe?

A common mistake made by proponents of young-Earth creationism is to assume that if evidence can be interpreted in a way that is consistent with one interpretation of young-Earth cosmic and geologic history, then that evidence does not support an old-Earth view and therefore should not concern them. However, this is quite wrong. Evidence can tend to confirm a hypothesis even if it can be interpreted consistently with an alternative view. To count as confirmatory evidence, the hypothesis in question only needs to be more likely to be true than false. The more such evidence has to be reinterpreted to align with the young-Earth view, the more ad hoc and therefore implausible the young-Earth origins model becomes.

One attempt to salvage young-earth creationism that I often encounter from secular creationists (though less frequently from academics) is to posit that the earth and universe were created already mature, similar to Christ’s transformation of water into mature wine (John 2:1-11). To many, this positing has the appeal of allowing evidence of vast age to be dismissed as saying nothing about the actual age of the earth, much as Adam, having been created mature, would appear to be much older than he really was. However, this explanation will not work because the geological record seems to tell a story of historical events, including the existence of the death of animals long before man, something that young-earth interpretations of Scripture typically exclude (though I find no compelling biblical arguments for this).

Furthermore, there is a remarkable correlation between the dates given by radiometric dating methods and the types of organisms found in the strata. For example, if you were to give a paleontologist a date given by radiometric dating techniques (say, for example, a rock dated to the Cambrian Period), he could predict, with precision, what organisms you might expect to be preserved in rocks dated to that age, as well as what you might not expect to find—regardless of where in the world they were identified. This remarkable correlation is quite unexpected in an interpretation of the geologic history of the young Earth, but entirely unsurprising in an interpretation of the ancient Earth.

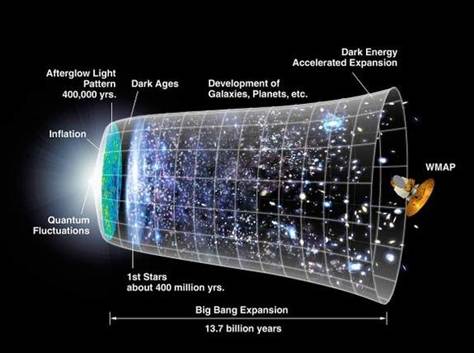

Our observation of distant galaxies, often millions of light years from Earth (meaning that the light leaving those stars takes millions of years to be observed by an observer on Earth), is also something quite expected in an old Earth interpretation, but quite surprising in a young Earth interpretation. The claim that light is created in transit will not help here, since we are able to observe events in deep space (such as supernovae) that, from that point of view, would be merely illusory (since the light would never have actually left those events in the first place). This would mean that much of our stellar observations are illusory, an implication that I find very problematic. While one can try to posit complex ad hoc rationalizations for light from distant stars, as some have done, it should still be recognized as much less surprising in an old Earth view than in a young Earth view, and therefore the evidence confirms the old Earth view.

Another major difficulty is the need to postulate that all meteorite impacts with the earth have taken place within the last six thousand years, including the one that caused the meteorite crater in the Gulf of Mexico, thought to have caused the extinction of the dinosaurs, 65 million years ago, as well as the meteorite that caused the Vredefort Dome, thought to be the largest impact crater in the world, located in Potchefstroom, South Africa. The latter is thought to have taken place over two billion years ago. If any of those impacts had occurred within the last six thousand years (as young Earth creationism demands), the effect on human civilization and animal life worldwide would have been devastating, and yet there is no evidence that such impacts have occurred in recorded history. Although some geologists have historically held that the Vredefort Dome is the result of a volcanic event, this is a minority view that is not widely accepted today. The consensus view is that this is a meteorite impact zone, and several lines of evidence support this, including evidence of shock on quartz grains and evidence of rapid melting of the granite into glass.

This is just the beginning of the scientific challenges to young-Earth creationism. Taken together, the numerous lines of evidence that point convergently in the direction of an old earth and cosmos are quite overwhelming. While I could talk for some time about the scientific challenges to young-Earth creationism (perhaps a topic for a future article), the main purpose of this article is to assess to what extent, if any, the Genesis text inclines us toward a young-Earth interpretation of cosmic and terrestrial history. To this I turn now.

Can the days of creation be interpreted as literal and consecutive while rejecting young earth creationism?

Before addressing the question of whether the “days” of the creation week are best understood as literal and consecutive, I will first assess whether it is possible to take the “days” as literal and consecutive while rejecting the implication of young-earth creationism. There are two major schools of thought that answer this question in the affirmative, so I will offer a brief analysis of these approaches here.

In 1996, John Sailhamer proposed the view (which he calls “historical creationism”) that while Genesis 1:1 describes the creation of the universe, Genesis 1:2–2:4 describes a one-week period (i.e., seven solar days) during which the promised land was prepared and human beings were created therein. [2] Sailhamer’s book has some notable endorsements, including John Piper [3] , Mark Driscoll [4] , and Matt Chandler [5] .

Sailhamer argues that the meaning of “earth” in verse 1 is different from the meaning in verse 2. He argues that in verse 1, its connection to the word “heavens” indicates that it is being used to refer to the cosmos. According to him, “When these two terms [heaven and earth] are used together as a figure of speech, they take on a distinct meaning on their own. Together, they mean much more than the sum of the meanings of the two individual words.” [6] When these words are used together, Sailhamer argues, “they form a figure of speech called a ‘merism.’ A merism combines two words to express a single idea. A merism expresses “wholeness” by combining two contrasts or two extremes.” [7] Sailhamer uses the example of David’s claim that God knows the way he sits and rises . [8] This claim expresses the fact that God has exhaustive knowledge of everything he does (Ps 139). Thus, Sailhamer concludes, “the concept of ‘all’ is expressed by combining the two opposites ‘my sitting down’ and ‘my rising up.'” [9] Sailhamer draws the parallel between this and the reference to heaven and earth in Genesis 1:1. He notes that “by uniting these two extremes in a single expression – ‘heaven and earth’ or ‘heavens and earth’ – the Hebrew language expresses the totality of all that exists. Unlike English, Hebrew does not have a single word to express the concept of ‘the universe’; it must do so by a merism. The expression ‘heaven and earth’ thus represents the ‘totality of the universe.'” [10] Sailhamer argues (correctly in my view) that Genesis 1:1 is not, as some have suggested, a title or summary of the chapter, but refers to a distinct divine act that took place before the six days described in the remainder of the chapter . [11]

If Genesis 1:1 alone describes the creation of the universe, what is the rest of the chapter about? Sailhamer suggests that it describes God preparing the promised land for human occupation. He points out, correctly, that the Hebrew word אֶ֫רֶץ (“eretz”) generally refers to a localized region of the planet, rather than the Earth as a whole, so it is quite legitimate to translate the word as “land” rather than “Earth.” For example, the very word “land” is contrasted in Genesis 1:10 with the seas. Sailhamer notes that “‘seas’ do not cover the ‘land,’ as would be the case if the term meant ‘Earth.’ Rather the ‘seas’ lie adjacent to and within the ‘land’ . ” [12]

Sailhamer argues that the expression תֹ֙הוּ֙ וָבֹ֔הוּ (“tohu wabohu”) is best translated not as “formless and void” (suggesting that the earth was a formless mass) but as “desert,” which he argues sets the stage for God to make the earth habitable for mankind.

One concern I have about Sailhamer’s thesis is that while it is true that the phrase “the heavens and the earth” is a merism referring to the entire universe, this merism appears not only in Genesis 1:1, but also in 2:1, which says “So the heavens and the earth were finished, and all their host.” This verse seems to indicate that the entirety of Genesis 1 refers to the heavens and the earth, that is, to the universe as a whole, and not just to a localized region of the earth. The Sabbath command also refers to God making in six days “the heaven and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them” (Exodus 20:11). This also seems to strongly suggest that the perspective of Genesis 1 is global rather than local. Another problem is that it seems quite unlikely that the word “Earth” refers in Genesis 1 to any specific “land,” since “Earth” is contrasted with the seas (Gen 1:10). Furthermore, the waters of the fifth day are populated by the great sea creatures (Gen 1:21), indicating that it refers to the oceans.

A more recent attempt to harmonize an interpretation of the days of creation that takes them to be literal and consecutive, known as the cosmic temple view, has been proposed by Old Testament scholar John Walton of Wheaton College. [13] Walton interprets the days of creation as a chronological sequence of twenty-four-hour days. However, he writes that these days “are not given as the period of time during which the material cosmos came into existence, but rather the period of time devoted to the inauguration of the functions of the cosmic temple, and perhaps also its annual re-creation . ” [14]

Walton argues that Genesis 1 is not concerned with material origins at all. Instead, he claims that the text is concerned with the assignment of functions. Walton argues that, during the days of the creation week, which he takes to be regular solar days, God was “establishing functions” [15] and “installing his functionaries” [16] for the created order. Walton admits that “theoretically it could be both. But to assume that we simply must have a material account if we are to say anything meaningful is cultural imperialism.” [17] Walton argues that the thesis he proposes “is not a view that has been rejected by other scholars; it is simply one that they have never considered because its material ontology was a blind presupposition to which no alternative was ever considered.” [18] However, as philosopher John Lennox rightly notes, “Surely, if ancient readers thought only in functional terms, the literature would be full of it, and scholars would be well aware of it?” [19 ]

Furthermore, it is not clear what exactly is involved in God assigning functions to the sun and moon, and to land and sea creatures, if, as Walton argues, this has nothing to do with material origins. Analytic philosopher Lydia McGrew also notes that [20] ,

…it is difficult to understand what Walton means by God establishing functions and installing officials in a sense that has nothing to do with material origins! Perhaps the most charitable thing to do would be to throw up one’s hands and conclude that the book is radically confusing. What could it mean that all the plants were already growing, providing food for animals, the sun was shining, etc., but that these entities were nonetheless functionless prior to a specific set of 24-hour days in a specific week?

What would the creation week have been like from the point of view of an earthly observer? According to Walton, “The observer in Genesis 1 would see day by day that everything was ready to do for people everything it had been designed to do. It would be like visiting a campus just before the students were ready to arrive, to see all the preparations that had been made and how everything had been designed, organized, and built to serve the students.” [21] Furthermore, Walton asserts, the “major elements missing from the ‘before’ picture are therefore humanity in the image of God and the presence of God in his cosmic temple . ” [22]

Walton claims that in the ancient worldview it was possible for something to exist materially but not to exist functionally. He claims that “people in the ancient world believed that something existed not in virtue of its material properties but in virtue of its function in an ordered system. Here I am not referring to an ordered system in scientific terms, but to an ordered system in human terms, that is, in relation to society and culture.” [23] Walton places much emphasis on the meaning of the Hebrew verb בָּרָ֣א (“bara”), meaning “to create.” He gives a list of words that form objects of the verb בָּרָ֣א and claims that the “grammatical objects of the verb are not easily identifiable in material terms.” [24] Walton lists the purpose or function assigned to each of the created entities. He then attempts to suggest that “a large percentage of contexts require a functional understanding.” [25] This, however, does not preclude a material understanding. Even stranger is Walton’s claim that “this list shows that the grammatical objects of the verb are not easily identified in material terms, and even when they are, it is questionable whether the context reifies them.” [26] However, the chart Walton presents lists objects of the verb that are material entities—including people, creatures, a cloud of smoke, rivers, the starry host, and so on. It is true that not all of these uses of the verb בָּרָ֣א refer to special creation de novo . For example, the creation of Israel (Isaiah 43:15) was not a special material creation de novo by divine decree. However, even our verbs “create” and “make” can have this flexibility of meaning, and their precise usage can be discerned from context. If I say I am going to create a new business, I do not mean that I am going to create employees and office space de novo . Similarly, when the psalmist calls upon God to “create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me” (Ps 51:10), although “create” is not used here in a material sense, the gender is clearly poetic, so one must be careful in extrapolating the meaning from a metaphorical use of the word to its ordinary usage. A further problem with Walton’s interpretation of the verb בָּרָ֣א as having only a functional interest in Genesis 1 is the fact that, as C. John Collins has pointed out, “1:26–31 are parallel to 2:4–25; this means that the ‘forming of man from dust’ (2:7), and the ‘building’ of woman from man’s rib (2:22), are parallel descriptions of the ‘creation’ of the first human of 1:27. Hence it makes sense to read 1:26–31 as if it were of only functional interest in Genesis 1.”27 as a description of a material operation” [27] .

Michael Jones, a popular Christian apologist on YouTube, has in recent years defended Walton’s thesis. To Walton’s arguments in support of his claim that Genesis 1 does not refer to material origins, Jones adds a very strange argument [28] : he quotes Jeremiah 4:23-26, which says of Israel

23. I looked at the earth, and behold, it was formless and void, and the heavens were without light . 24. I looked at the mountains, and behold, they trembled, and all the hills quaked. 25. I looked, and behold, there was no man, and all the birds of the air had fled. 26. I looked, and behold, the fruitful land was a wilderness, and all its cities were laid waste before the LORD, before his fierce anger.

Jones comments [29] ,

If Genesis 1 is about the material creation of all things, we should expect the same language in reverse to be the disintegration of the materials being spoken of. However, when Assyria conquered Israel and deported all the elites, we are not suggesting that the fabric of space/time was torn open and the land of Israel disappeared. Rather, we understand that the kingdom went from a functioning, productive society to a chaotic land. The sunlight did not literally stop shining in that region. It was just part of the cultural expression to say that the kingdom went from an ordered society to disorder. And so the reverse in Genesis 1 would only suggest that God took a disordered chaos and ordered it to be a functioning temple for himself and the humans in it, not the beginning of all matter as we know it.

Although Michael Jones has a brilliant mind and has made very welcome contributions to the field of apologetics, this interpretation reflects a total disregard for Jeremiah’s rhetoric. The prophet is using a representation as if the sun had gone out, and “there was no man, and all the birds of the air had fled.” He is not making an ontological claim.

Furthermore, the arguments Walton adduces in support of his claim that in the ancient worldview it was possible for something to exist materially but not exist functionally seem to me to be very weak, and even seem to undermine his position. Walton, for example, claims that in Hittite literature there is a creation myth which speaks of “cutting up heaven and earth with a copper cutting tool.” [30] He also cites the Egyptian Insinger Papyrus which states concerning the god: “He created food before those who are living, the wonder of the fields. He created the constellation of those in heaven, for those on earth to learn of. He created in it the sweet water which all lands desire.” [31] Walton also says that the Babylonian creation epic, Enuma Elish , has Maduk “harnessing the waters of Tiamat in order to provide the basis for agriculture.” It includes the piling up of earth, the freeing of the Tigris and Euphrates, and the digging of wells to handle the water catchment.” [32] It is not clear to me, however, how these texts support Walton’s thesis. No argument is offered as to why the ancients did not believe that the gods physically separated the heavens from the earth. The fact that we as modern readers take at face value the reading of these texts as manifestly false does not mean that an ancient audience necessarily would have done so. Nor does Walton offer any argument to support the conclusion that the author or audience of the Tigris and Euphrates text did not interpret the text to say that Marduk physically freed the rivers and built the wells to handle the water catchment.

Another key issue here is that there is no reason to believe that functional assignment and concern for material origins are mutually exclusive. It is not logical to think that since the word בָּרָ֣א is often associated with a mention of functional assignment, it does not have any connotations about material origins. Functional assignment and material origins go hand in hand, as material design is what enables an entity to perform its function.

Having rejected interpretations that propose to harmonize an old earth view with an interpretation of the creation week as a series of six consecutive solar days, we must now address the question of which interpretive paradigm best makes sense of the text of Genesis 1, and it is to this question that I now turn.

In the Beginning

In Genesis 1:1-3, we read,

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. 2 The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the surface of the waters. 3 Then God said, “Let there be light.” And there was light .

It has often been pointed out that verse 3 marks the first occurrence of the phrase “And God said…”. This expression is used to denote the beginning of each of the six days of creation week (vv. 3, 6, 9, 14, 20, 24). Therefore, it can be argued that the first day of creation week actually begins in verse 3, not verse 1. Therefore, by the time the first day of creation week is reached, the heavens and the earth are already in existence. Therefore, regardless of what one thinks about the age of the biosphere (a separate discussion), Scripture is completely silent on the age of the Universe and the Earth – even if the days of creation week are taken as literal and consecutive. Furthermore, when God says “let there be light” (Gen 1:3), marking the beginning of the first “day” of the creation week, this can be understood as God calling forth the dawning of the first day, since the expression “let there be…” does not necessarily indicate that something has come into existence – for example, the psalmist says ” let your mercy, O Lord, be upon us” (Ps 33:22), which does not imply that God’s mercy had not been with them before.

This argument is not without objection. For example, some authors view verse 1 as a summary of the entire narrative, rather than describing an event that took place some indeterminate time before the first day of the creation week . [33] However, Hebrew scholar C. John Collins points out that this interpretation is less likely, since “the verb created in Genesis 1:1 is in the past perfect, and the normal use of the past perfect at the beginning of a pericope is to denote an event that took place before the narrative gets going.” [34] John Sailhamer also adduces some reasons that make it more likely that Genesis 1:1 describes an event that occurred before the creation week, rather than being a summary title . [35] First, Genesis 1:1 is a complete sentence and makes a statement, which is not how titles are formed in Hebrew. For example, Genesis 5:1 serves as a heading for the verses that follow, and reads, “This is the book of the generations of Adam.” Second, verse 2 begins with the conjunction “and.” This, however, is surprising if Genesis 1:1 is intended to be a summary heading for the entire chapter. Sailhamer notes that if 1:1 were a summary heading, “the section that follows it would not begin with the conjunction ‘and.'” [36] Third, there is a summary statement of chapter 1 found at its conclusion, in 2:1, which would make a summary heading at the beginning of the chapter redundant. It seems highly unlikely that the account would have two summary headings.

Perhaps the strongest argument for understanding Genesis 1:1 as a summary title for the entire passage has been put forward by Bruce Waltke. [37] He argues that the combination “the heavens and the earth” is a merism referring to “the organized universe, the cosmos.” [38] He argues that “this compound never has the meaning of disordered chaos, but always of an ordered world.” [39] He further argues that “disorder, darkness, and depth” suggest “a situation not tolerated in the perfect cosmos and are never said to have been called into existence by the word of God.” [40] However, C. John Collins responds to this argument by pointing out that the expression “formless and void” (Gen. 1:2) is not a phrase referring to “disordered chaos,” but rather describes the earth as “an unproductive and uninhabited place.” [41] And he notes that “there is no indication that the ‘deep’ is any kind of opponent to God; in fact, throughout the rest of the Bible it does God’s bidding and praises Him (cf. Gen. 7:11; 8:1; 49:25; Ps. 33:7; 104:6; 135:6; 148:7; Prov. 3:20; 8:28). And since God names the darkness (Gen. 1:5), there is no reason to believe that it opposes His will either . ” [42]

In any case, although there is an ongoing scholarly debate between those opposing interpretations, the reading of Genesis 1:1 as describing events taking place before the creation week is at the very least plausible, if not the most favorable as the most likely meaning. Thus, there is certainly no room for dogmatism that Genesis 1 commits us to a young Universe or Earth, regardless of what one thinks about the age of the biosphere (which will relate to how one understands the “days” of the creation week).

Some scholars argue that Genesis 1:1 should be translated as follows: “When God began to create the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void…” [43] This reading would be consistent with Genesis 1 not referring to the special creation of the Universe out of nothing, but to bringing order and organization to a chaotic, formless void. However, C. John Collins claims that “the simplest rendering of the Hebrew we have is the conventional one (which is how the ancient Greek and Latin versions took it).” [44] The main argument for this alternative translation is the lack of a definite article in the opening words. The text we have reads בְּרֵאשִׁית (“bere’shit”), while proponents of the translation in question would argue that the traditional rendering would make more sense if it read בָּרֵאשִׁית (“bare’shit”). However, as C. John Collins notes, “Since we have no evidence that any ancient author found this to be a problem, the conventional reading stands.” [45] This is also a matter of ongoing scholarly debate. Even if the alternative reading is correct, however, we would not lose anything, since many other biblical texts indicate that the Universe is temporally finite, and that God brought it into existence ex nihilo .

Are the “days” of Genesis 1 literal?

The debate over the interpretation of Genesis 1 has tended to focus on the correct translation of the Hebrew word יוֹם (“yom”). Perhaps the best-known representative of the old-earth position is Hugh Ross of Reasons to Believe, although I often find his interpretations somewhat forced and far-fetched. Hugh Ross notes that “the Hebrew word yom, translated ‘day,’ is used in biblical Hebrew (as in modern English) to indicate any of four periods of time: (a) some portion of daylight (hours); (b) from sunrise to sunset; (c) from sunset to sunset; or (d) a segment of time without any reference to solar days (from weeks to a year to several years to an age or epoch.” [46] This is correct, but, as in modern English, context allows the reader to discern which of these literal meanings is at play.

In Genesis 2:4, we read,

These are the origins of the heavens and the earth when they were created, in the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens .

Here, the Hebrew word יוֹם refers to an indefinite but finite period of time, corresponding to definition (d) offered by Hugh Ross above. However, the context makes it apparent that this is the reading under consideration. In English, we also use expressions like “in those days” to refer to an indefinite but finite period of time, and there is no ambiguity about whether it refers to a literal day or a longer period of time. Likewise, we could say “the day was about to end,” and that would make it clear that the word “day” is to be understood as referring to daylight hours, corresponding to definition (a) of Ross’s literal set of meanings. Young-Earth creationists often respond to Ross’s proposed translation, rightly in my view, by observing that the use of the words “evening” and “morning,” combined with an ordinal number, in referring to the days of the creation week, makes it clear that a solar day is meant, whether 12 or 24 hours long. [47] What is often overlooked, however, is that settling the question of the translation of the word יוֹם does not in itself indicate whether it is intended to be understood literally or figuratively. Nor does it indicate whether the days are strictly consecutive, or whether there may be gaps between each of them. These are questions logically arising from the issue of translation and must be addressed separately.

Is there any instance in Scripture where the word יוֹם is clearly translated as “day” in the usual sense and yet is not meant to be understood literally? Indeed, it is. In Hosea 6:2, we read,

Come, let us return to the LORD. For He has torn us, and He will heal us; He has wounded us, and He will bind us up. 2. After two days He will revive us; on the third day He will raise us up, and we will live before Him.

The context here is that Israel has been subjected to God’s judgment. This text is a call for Israel to return to the Lord for healing and restoration. While the Hebrew word יוֹם is used here (the same word translated “day” in Genesis 1) in conjunction with an ordinal number, the word “day” is clearly used in a non-literal sense and almost certainly refers to a longer period of time. The use of the word “day,” when combined with an ordinal number, in a non-literal sense makes it possible that the word “day” in Genesis 1 is used in a non-literal sense as well. This does not make it probable by itself, but it at least opens up the possibility.

So what is the best way to understand the days of Genesis 1? There are a number of clues in the text that indicate the days are not to be understood literally. C. John Collins observes that while each of the six work days has the refrain “and there was evening and there was morning, the nth day,” this refrain is missing on the seventh day [48] . Collins suggests that this can be explained by positing that the seventh day on which God rested has not come to an end, like the other six days, but continues even to the present. In support of this, Collins appeals to two New Testament texts: John 5:17 and Hebrews 4:3-11. In the first reference, Jesus gets into trouble for having healed a man on the Sabbath. Jesus responds by saying that “But He said to them, ‘Hitherto my Father worketh, and I also work. ’” Collins suggests that Jesus should be interpreted here as saying, “My Father is working on the Sabbath, even as I am working on the Sabbath.” [49] Collins concludes that “we can explain this most easily if we take Jesus to be speaking to mean that the Sabbath of creation is still continuing.” [50] In Hebrews 4:3-11, the author of Hebrews quotes Psalm 95:11, which indicates that unbelievers will not enter God’s “rest” (v. 3). The author then notes that God “rested” on the seventh day (v. 4). The author claims that Joshua gave the Hebrews no “rest.” Since the context of Psalm 95:11 is that God forbade the Hebrews who had left Egypt to enter the promised land, the author of Hebrews’ claim that Joshua gave the people no true “rest” indicates that he does not understand Psalm 95:11 literally. Rather, there is a Sabbath rest that God’s people can enter. And how can God’s people enter God’s rest? Resting from your works as God did from His (v. 10). Collins concludes, “This makes sense if ‘God’s rest,’ which you entered on the Sabbath of creation, is the same ‘rest’ that believers enter, and therefore God’s rest is still available because it is still continuing.” [51] This interpretation is not modern. In fact, Augustine of Hippo wrote in his Confessions that the seventh day of creation “has no evening, nor does it have sunset, for you sanctified it to last forever.” [52] What are the implications of this idea? Collins notes, “If the seventh day is not ordinary, then we can begin to wonder if perhaps the other six days need to be ordinary . ” [53]

John Collins also points to Genesis 2:5-7, in which we read

5 Now no shrub of the field was yet on the earth, nor had any plant of the field yet sprouted, for the LORD God had not sent rain on the earth, and there was no man to till the ground. 6 But a mist went up from the earth and watered the whole face of the ground. 7 Then the LORD God formed man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.

Collins points out that this text “does not agree with the sequence of days in the first account: there God made the plants on the third day, as we find in 1:11-12” [54] . Furthermore, “in 2:5-6 these plants are said not to be there because it had not yet rained (which is the ‘ordinary providence’ reason for the plants not being there), whereas in Genesis 1 He created them (which is a special situation) [55] . “The best way to harmonize these texts is to consider that Genesis 2:5-7 refers to a localized region of the earth, not the globe as a whole, i.e., that in a specific region of the planet “not a single plant of the field had yet sprung up,” because it had not yet rained. That the origin of plants described in Genesis 1:11-12 refers to a different event than that described in Genesis 2:5-7 is evident, since Genesis 2:5 states that the reason the bushes and plants of the field had not sprouted was because there had been no rain, implying that the growth of plants relates to God’s ordinary providence, not to their special creation by divine decree, as in 1:11-12. In other words, it was the dry season. Collins notes that “in Palestine there is no rain during the summer, and the fall rains cause an explosion of plant growth. So verses 5-7 would make sense if we assume that they describe a time of year when it has been a dry summer, so plants are not growing; but the rains and man are about to come, so plants will be able to grow in the ‘ground’ [56] . Collins concludes: “The only way I can make sense of this explanation of ordinary providence given by the Bible itself is if I imagine that the cycle of rain, plant growth, and dry season had been going on for some number of years before this point, because the text says nothing about God not having yet made plants” [57] . If this is the case, then this would suggest that the length of the six days of creation could not have been that of an ordinary week, since it would imply that the cycle of seasons had been going on for some time.

It can be seen that Genesis 1:11-12 does not necessarily imply that God created fully developed plants de novo , since the text indicates that “The earth brought forth vegetation…” This would allow one to consider that the growth of plants was brought about by God’s establishment of the cycle of ordinary providence. However, since vegetation and fruit trees take more than a day to grow and develop by ordinary providence, this would still imply a creation week quite different in terms of length than our typical week. In my view, positing that Genesis 1:11-12 and Genesis 2:5-6 refer to distinct events, the latter being more local in scope, is the simplest and most natural explanation of the relevant data. This, for the reasons stated above, tends to suggest a creation week that is not identical in length to our regular seven-day week.

There are still further indications that the length of the creation week is not like our typical weeks. For example, many have pointed to the large number of events said to have taken place on the sixth day, which presumably would have taken longer than a single solar day. Collins lists the various things said to have occurred on the sixth day: “God makes the animals of the earth, forms Adam, plants the Garden and brings the man there, gives him instructions, sets him on a search for ‘a helper suitable for him’ (and during this search Adam names all the animals), puts him into a deep sleep, and makes a woman from his rib” [58] . Furthermore, when Adam joins the woman, Eve, whom God had formed, Adam replies, “This is at last bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh,” [59] suggesting that Adam has waited a long time for a helper suitable for him.

In addition to the discussion of whether the “days” of the creation week are to be understood literally or not, there is also the question of whether there is any reason to exclude the possibility of there being gaps between the days, even if those days are taken as regular days. Indeed, John Lennox suggests “that the writer did not intend for us to think of the first six days as days of a single earthly week, but rather as a sequence of six creation days; that is, days of normal length (with evenings and mornings, as the text says) in which God acted to create something new, but days that might well have been separated by long periods of time. We have already seen that Genesis separates the initial creation, “the beginning,” from the sequence of days. What we now further suggest is that the individual days might well have been separated from each other by unspecified periods of time” [60] . I am not aware of any linguistic reason to exclude this possibility.

To recap, although young-earth creationists are correct that the best translation of the Hebrew word יוֹם in the context of Genesis 1 is “day,” the text of Genesis 1 is consistent with the creation week being quite different from our ordinary weeks with respect to length. However, what is the best way to understand the nature of the creation days? It is to this question that I now turn.

An analog days approach

My view is closest to that advocated by C. John Collins, which he calls the analogical days view. [61] Collins notes that “the best explanation is one which sees these days as not being of the ordinary kind; they are, instead, ‘God’s work days.’ Our work days are not identical with them, but analogous. The purpose of analogy is to establish a pattern for the human rhythm of work and rest. The length of these days is not relevant for this purpose.” [62] One advantage of this approach is that one can understand the word “day” in its ordinary sense, but apply its meaning analogically, just as one does with other analogical expressions such as the “eyes of the Lord” (in that case, we need not propose an alternative translation of the Hebrew word for “eye,” but rather understand its ordinary meaning in an analogical sense).

The interpretation of analogical days also allows us to make sense of the Sabbath commandment in Exodus 20:8-11, where we read,

8. Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. 9. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, 10. but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the LORD your God. In it you shall not do any work: you, nor your son, nor your daughter, nor your male or female servant, nor your livestock, nor the stranger who is with you. 11. For in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day. Therefore the LORD blessed the Sabbath day and hallowed it.

Young Earth creationists argue that this text indicates that the creation week consisted of six ordinary days, since it is said to set a pattern for an ordinary work week. However, as Collins notes, “This misses two key points: the first is what we have already noted about creation’s rest being unique. The second is that our work and our rest cannot be identical to God’s; they are like God’s in some ways, but they are certainly not the same” [63] . Collins notes that there are obvious points of disanalogy between God’s work week and our own: “For example, when was the last time you spoke and made a plant grow? Rather, our planting, watering, and fertilizing are like God’s work, because they operate on what is there and make it produce something it would not have produced otherwise. Our rest is like God’s, because we stop working to look with pleasure at his works” [64] . On the other hand, God is said to have rested on the Sabbath. Collins notes that “That last word in Hebrew, ‘rested,’ has the sense of catching one’s breath after being exhausted (see Ex. 23:12; 2 Sam. 16:14); and I can assure you that you don’t mean that God needs that kind of respite (see Isa. 40:28-31 – God does not get tired). Rather, we need to view it as an analogy: there are points of similarity between the two things, but also points of difference” [65] . Of course, there is also an analogy between God’s work week and the six years of sowing the land followed by a seventh year of rest (Ex. 23:10-11).

One consideration I would add to Collins’ case is that the ancients often used numbers symbolically rather than literally. For example, the evangelist Matthew refers to three sets of “fourteen generations”—from Abraham to David, from David to the exile, and from the exile to Christ (Mt 1:17)—even though he has to double up and skip generations to make the math work. He probably does this because fourteen is the numerical value of David’s name in Hebrew, and Matthew intends to convey that Jesus is the promised Davidic heir. So it seems to me that it is not too far-fetched to speculate that perhaps something similar is going on in Genesis 1, where the number seven is used in a symbolic rather than literal sense.

There may also be other reasons, besides the analogy with the human work week, why the author of Genesis chose to use the number seven. Earlier in this article, I have criticized the cosmic temple view of Genesis 1 advocated by John Walton. However, one useful insight from Walton’s analysis is the parallel he draws between the biblical account of creation and that concerning the building of the tabernacle and temple. For example, he observes that “Isaiah 66:1 clearly expresses the function of the temple/cosmos in biblical theology, as it identifies heaven as God’s throne and earth as His footstool, providing Him with a place of rest. God also rests on the seventh day of creation, just as He rests in His temple . ” [66] The assertion that God rests in His temple is derived from Psalm 132:13-14, where we read: “For the LORD has chosen Zion; He has desired it for His dwelling place. This is my resting place forever; here I will dwell, for I have desired it.”

Walton further observes that “heavenly bodies are referred to using the unusual term ‘lights,’ which throughout the rest of the Pentateuch refers to the lights of the tabernacle’s lampstand” [67] . Furthermore, “the idea of rivers flowing from the holy place is found both in Genesis 2 (which we will suggest portrays Eden as the Holy of Holies) and in Ezekiel’s temple (Ezek. 47:1)” [68] . In a similar vein, Michael Fishbane further argues that [69] ,

Indeed, as Martin Buber long ago pointed out, there are a number of key verbal parallels between the account of the creation of the world and the description of the building of the tabernacle in the wilderness (compare Genesis 1:31; 2:1; 2:2; 2:3 with Exodus 39:43; 39:32; 40:33; and 39:43, respectively). Thus, “Moses saw all the work” that the people “did” in building the tabernacle; “and Moses completed the work” and “blessed” the people for all their labors.

… Itis evident, then, that the construction of the tabernacle has been presented in the image of the creation of the world, and signified as an extension of a process begun at creation.

Walton also points to Exodus 40:34 and 1 Kings 8:11, which indicate that the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle and the temple respectively . [70] Walton compares these texts with Isaiah 6:3, which describes Isaiah’s vision in the temple, where the seraphim are shouting to one another, saying “Holy, Holy, Holy, is the LORD of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory.” Another connection between creation and the temple is Psalm 78:69, which says, “He built his sanctuary like the heights, like the earth which he has founded forever.”

Now this is where it gets interesting in relation to the seven “days” described in the creation account. G.K. Beale observes that [71] ,

More specifically, both the creation and tabernacle-building accounts are structured around a series of seven acts: cf. “And God said” (Gen. 1:3, 6, 9, 14, 20, 24, 26; cf. vv. 11, 28, 29) and “the LORD said” (Ex. 25:1; 30:11, 17, 22, 34; 31:1, 12) (Sailhamer 1992: 298-299). In light of observing similar and additional parallels between the “creation of the world” and “the building of the sanctuary,” J. Blenkinsopp concludes that “the place of worship is a cosmos on a scale” (1992: 217-218).

Levenson also suggests that the same cosmic significance follows from the fact that Solomon took seven years to build the temple (1 Kgs. 6:38), that he dedicated it in the seventh month, during the Feast of Tabernacles (a seven-day festival [1 Kgs. 8]), and that his dedication speech was structured around seven petitions (1 Kgs. 8:31–55). The building of the temple thus appears to have been inspired by the seven-day creation of the world, which also coincides with the seven-day construction of temples elsewhere in the Ancient Near East (Levenson 1988:78–79). Just as God rested on the seventh day from his work of creation, when the creation of the tabernacle and especially the temple is finished, God takes a “resting place” in it.

Perhaps, therefore, the organization of the creation account around seven days is one aspect of the intended parallelism between creation and the temple or tabernacle, which would provide another reason why the number seven may be used in a symbolic sense in Genesis 1.

Are the days of creation ordered chronologically?

Another question we must address is whether the text of Genesis 1 requires us to take the days as being in chronological sequence, and if so, whether that poses any problems. The major problem with the chronological interpretation of the days of creation is that photosynthetic plants are created before the sun. In fact, the sun is not created until the fourth day. Hugh Ross points out that technically, the text does not indicate that the sun and moon arose on the fourth day. Rather, the text only reports that God said, “Let there be lights in the expanse of the heaven to separate the day from the night. And let them be for signs and for seasons, for days and for years, and let them be for lights in the expanse of the heaven to give light on the earth.” [72 ] Furthermore, “Genesis 1” employs a set of verbs for the creation of birds, mammals, human beings, and the universe. These verbs —bara, asa, and yasar— mean ‘to create,’ ‘to make,’ and ‘to design’ or ‘to form,’ respectively. Another verb, haya , means ‘to exist, be, occur, or happen’ and is used in conjunction with the appearance of ‘light’ on the first day and of ‘lights in the expanse of the sky’ on the fourth day . ” [73] Ross suggests that this is “consistent with the starting point of the creation week at the advent of light on the Earth’s surface – that divinely orchestrated moment when light first penetrated the opaque medium enveloping the primordial planet.” [74] Ross further argues that on the fourth day “God transformed the Earth’s atmosphere from translucent to transparent. At that point, the Sun, Moon, and stars became visible from the Earth’s surface as distinct sources of light.” [75] I am not convinced by this proposal, since it seems to run into the problem that photosynthetic plants were deprived of light for a significant portion of Earth’s history.

An alternative scenario, proposed by C. John Collins, seems more appealing to me. Collins points out that the Hebrew verb used in Genesis 1:16, יַּ֣עַשׂ (“asa”), meaning “to make,” “does not specifically mean ‘create’; it may refer to that, but it may also refer to ‘working on something that is already there’ (hence the ESV margin), or even ‘appointed’.” [76] He therefore argues that “verse 14 focuses on the function of the luminaries rather than their origin: the verb there is is completed by the purpose clause, ‘set apart. ’ The account of this day therefore focuses on these luminaries fulfilling a function that God appointed for man’s welfare, and that they fulfill that function at God’s command, implying that it is foolish to worship them . ” [77]

Apart from the issue that the sun, moon, and stars did not appear until the fourth day (which I think Collins has satisfactorily resolved), I see no further chronological incompatibilities between the Genesis 1 account and the scientific evidence.

However, if we are not convinced by either Ross’s or Collins’s proposal, would it be a valid alternative approach to posit that the “days” of creation are arranged without regard to chronology? I will now examine this question.

Many have pointed out that days one through three form a triad that corresponds to that formed by days four through six. On day one, God creates light and distinguishes it from darkness; while on day four, God creates the sun, moon, and stars. On day two, God separates the sky and the sea; while on day five, God creates birds and sea creatures. On day three, God brings dry land into view; while on day six, God creates land animals and human beings. Some have argued that this pattern indicates that the exact chronological sequence of events is not in mind. This observation forms the basis of the literary frame view, first proposed by Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744–1803) [78] . Mark Throntveit also argues that this structural organization of the text suggests that the sequence of days is not intended to express a chronological sequence [79] . However, as many have rightly pointed out in response to this argument, literary setting and chronological sequence are not necessarily mutually exclusive . [80]

Otro argumento para considerar que los días están ordenados anacrónicamente son las supuestas contradicciones entre la secuencia de acontecimientos descrita en Génesis 1 y 2. Ya he abordado una de ellas mostrando que Génesis 2 se centra en una región geográfica concreta. La otra contradicción que a veces se alega es que Génesis 2:19 indica que la creación de los animales tuvo lugar después de que la humanidad entrara en escena, como sugieren algunas traducciones. Sin embargo, Collins sostiene que el verbo hebreo debería traducirse por el pluscuamperfecto “había formado”, lo que resuelve este problema[81].

No obstante, hay que reconocer que los antiguos no siempre narraban cronológicamente. A veces narraban los acontecimientos anacrónicamente (aunque, hay que señalar, sin utilizar marcadores cronológicos como “al día siguiente”). Por ejemplo, en la tentación de Cristo, que se narra en Mateo 4 y Lucas 4, los dos relatos no cuentan las tres tentaciones en el mismo orden. Mateo relaciona los acontecimientos utilizando la palabra Τότε (que significa “entonces”), mientras que Lucas relaciona los acontecimientos utilizando la palabra Καὶ (que significa “y”). Por esta razón, me inclino a creer que Mateo representa los acontecimientos en orden cronológico, mientras que Lucas los representa anacrónicamente. Así pues, la clave para determinar si Génesis 1 compromete a sus lectores a interpretarlo como un relato cronológico de los acontecimientos es dilucidar si hay algún marcador cronológico concreto en el texto que lleve a su audiencia original a creer que se está describiendo una sucesión secuencial de acontecimientos.

En 1996, David A. Sterchi publicó un artículo en el Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. En este artículo argumentaba que, aunque la estructura y la sintaxis de Génesis 1 no excluyen la secuencia cronológica, tampoco la exigen[82]. Señala que los cinco primeros días de la creación carecen de artículo definido, aunque los días seis y siete sí lo tienen. Así, estas frases se traducen más adecuadamente “un día… un segundo día… un tercer día… un cuarto día… un quinto día”. Sterchi sugiere que “el texto no está implicando una secuencia cronológica de siete días. Por el contrario, simplemente presenta una lista de siete días”[83]. Además, argumenta que “por un lado, había un compromiso con la verdad al informar sobre el relato en el texto. Por otro, el deseo de utilizar una estructura literaria para reforzar su mensaje. Una forma de lograr la libertad literaria y seguir manteniendo la verdad en el proceso era eliminar los límites de la sintaxis cronológica. Así, el autor optó por dejar los días indefinidos y utilizó el artículo en los días seis y siete para enfatizar, no para determinar”[84].

Si los acontecimientos se narran cronológicamente, ¿hay alguna hipótesis plausible de por qué la creación del sol y la luna no se menciona hasta el cuarto día? Yo creo que sí. Johnny Miller y John Soden señalan que el orden de los acontecimientos entre el relato de la creación del Génesis y el de los egipcios es sorprendentemente similar, aunque hay diferencias clave, una de las cuales es que la aparición del sol es el acontecimiento inicial y principal en el mito egipcio de la creación, mientras que el sol se retrasa hasta el cuarto día en el relato bíblico[85]. Señalan que “la problemática no es tanto el cambio de orden (sigue siendo el mismo, salvo por la aparición de la vida vegetal). Más bien el uso de la ‘semana’ en la creación en lugar de un solo día retrasa el acontecimiento de la salida del sol de la primera mañana hasta el cuarto día. El sol ya no es la fuerza dominante o el rey sobre los dioses (aunque debía “gobernar el día”; Gn. 1:16). El sol es una más de las creaciones sumisas de Dios, que cumple sus órdenes y sirve a su voluntad. La imagen resultante resta importancia al sol, el actor principal de Egipto. En cambio, Dios brilla claramente como el soberano y trascendente gobernador de la creación. El clímax es la creación de la humanidad como representante de Dios”[86]. En relación con este motivo también está la omisión de los nombres del sol y la luna, que eran venerados como deidades por los egipcios; en su lugar, estos cuerpos celestes se denominan “la lumbrera mayor” y “la lumbrera menor”.

Resumen

Para concluir, no se puede, a mi juicio, sostener que los “días” de la creación son una serie de seis días solares consecutivos y rechazar al mismo tiempo una interpretación de la Tierra joven. Aunque Sailhamer y Walton, entre otros, han intentado hacerlo, mi evaluación de sus respectivos enfoques es que no logran armonizar esta interpretación con una Tierra antigua. Además, el relato del Génesis no dice nada sobre la edad del Universo o de la Tierra, ya que éstos son creados antes del comienzo del primer día de la semana de la creación. Por lo tanto, la única cuestión que debe evaluarse es la edad de la biosfera. Además, hay algunas pistas en el texto de Génesis 1 que son consistentes con que la semana de la creación fue más larga que nuestras semanas regulares. Se puede armonizar el texto de Génesis 1 con una interpretación de la Tierra antigua planteando la presencia de brechas entre cada uno de los “días” o planteando que los “días” no son literales. La interpretación analógica de los días sugerida por Collins y otros es la interpretación no literal más plausible de los días. Aunque la estructura y la sintaxis del pasaje son consistentes con que los días estén ordenados cronológicamente, no lo requieren.

Notas de páginas

[1] Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1997), 570–571.

[2] John Sailhamer, Genesis Unbound: A Provocative New Look at the Creation Account (Colorado Springs, CO: Multnomah Books, 1996), kindle.

[3] John Piper, “What Should We Teach About Creation?” Desiring God, June 1, 2010 (http://www.desiringgod.org/interviews/what-should-we-teach-about-creation)

[4] Mark Driscoll, Doctrine: What Christians Should Believe (Wheaton, IL, Crossway, 2011), 96 (Doctrina: Lo que cada cristiano debe creer)

[5] Matt Chandler, The Explicit Gospel (Wheaton, IL, Crossway, 2012), 96-97 (El evangelio explícito)

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009).

[14] Ibid., 91

[15] Ibid., 64

[16] Ibid., 92

[17] Ibid., 170.

[18] Ibid., 42.

[19] John C. Lennox, Seven Days That Divide the World: The Beginning according to Genesis and Science (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), 132. (El principio según el Génesis y la Ciencia)

[20] Lydia McGrew, “Review of John H. Walton’s The Lost World of Genesis One,” What’s Wrong with the World, March 12, 2015. http://whatswrongwiththeworld.net/2015/03/review_of_john_h_waltons_the_l.html

[21] John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009), 98.

[22] Ibid., 96.

[23] Ibid., 24.

[24] Ibid., 41.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] C. John Collins, “Review of John Walton, The Lost World Of Genesis One,” Reformed Academic, May 22, 2013.

[28] Michael Jones, “Genesis 1a: And God Said!” Inspiring Philosophy, June 7, 2019, YouTube video, 22:42, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R24WZ4Hvytc

[29] Ibid.

[30] John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009), 30.

[31] Ibid., 32.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Bruce Waltke, “The Creation Account in Genesis 1:1–3, Part III: The Initial Chaos Theory and the Precreation Chaos Theory,” Bibliotheca Sacra 132 (July–September 1975), 216–228.

[34] C. John Collins, Genesis 1-4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2011), kindle.

[35] John Sailhamer, Genesis Unbound: A Provocative New Look at the Creation Account (Colorado Springs, CO: Multnomah Books, 1996), kindle.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Bruce Waltke, “The Creation Account in Genesis 1:1–3, Part III: The Initial Chaos Theory and the Precreation Chaos Theory,” Bibliotheca Sacra 132 (July–September 1975), 216–228.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] C. John Collins, Genesis 1-4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2011).

[42] Ibid.

[43] The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) se opta por esta traducción.

[44] C. John Collins, Reading Genesis Well: Navigating History, Poetry, Science, and Truth in Genesis 1–11 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2018), 160–161.

[45] Ibid., 161.

[46] Hugh Ross, A Matter of Days: Resolving a Creation Controversy (San Francisco, CA: RTB Press, 2015), 74.

[47] Jonathan Sarfati, Refuting Compromise: A Biblical and Scientific Refutation of “Progressive Creationism” (Billions of Years) As Popularized by Astronomer Hugh Ross (Creation Book Publishers; 2nd edition, 2011), kindle.

[48] C. John Collins, Science & Faith: Friends or Foes? (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2003), 62.

[49] Ibid., 84-85.

[50] Ibid., 85.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Saint Augustine Bishop of Hippo, The Confessions of St. Augustine, trans. E. B. Pusey (Oak Harbor, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1996) (San Agustín de Hipona, Confesiones)

[53] C. John Collins, Science & Faith: Friends or Foes? (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2003), 85.

[54] Ibid., 87.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid., 88.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Ibid., 89.

[59] Ibid.

[60] John C. Lennox, Seven Days That Divide the World: The Beginning According to Genesis and Science (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), 54. (El principio según el Génesis y la Ciencia)

[61] C. John Collins, Science & Faith: Friends or Foes? (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2003), 90.

[62] Ibid., 89.

[63] Ibid., 86.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] John H. Walton, Genesis, The NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 148.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Michael Fishbane, Text and Texture (New York: Schocken, 1979).

[70] John H. Walton, Genesis, The NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 149.

[71] G. K. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God, ed. D. A. Carson, vol. 17, New Studies in Biblical Theology (Downers Grove, IL; England: InterVarsity Press; Apollos, 2004), 61.

[72] Hugh Ross, A Matter of Days: Resolving a Creation Controversy (San Francisco, CA: RTB Press, 2015), 80-82.

[73] Ibid., 82.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ibid.

[76] C. John Collins, Genesis 1-4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2011), kindle.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Johann Gottfried von Herder, The Spirit of Hebrew Poetry, trans. James Marsh (Burlington, Ontario: Edward Smith, 1833), 1:58. See also Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1–15, Word Biblical Commentary (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1987), 6–7.

[79] Mark Throntveit, “Are the Events in the Genesis Account Set Forth in Chronological Order? No,” The Genesis Debate (ed. R. Youngblood; Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1986) 36–55.

[80] John C. Lennox, Seven Days That Divide the World: The Beginning according to Genesis and Science (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), (El principio según el Génesis y la Ciencia)

[81] C. John Collins, “The Wayyiqtol as ‘Pluperfect’: When and Why?” Tyndale Bulletin 46, no. 1 (1995): 117–40.

[82] David A. Sterchi, “Does Genesis 1 Provide a Chronological Sequence?” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society (December 1996), 529-536.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Johnny V. Miller and John M. Soden, In the Beginning … We Misunderstood: Interpreting Genesis 1 in Its Original Context (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 2012), 106.

[86] Ibid.

Recursos recomendados en Español:

Stealing from God ( Paperback ), ( Teacher Study Guide ), and ( Student Study Guide ) by Dr. Frank Turek

Why I Don’t Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist ( Complete DVD Series ), ( Teacher’s Workbook ), and ( Student’s Handbook ) by Dr. Frank Turek

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Dr. Jonathan McLatchie is a Christian writer, international speaker, and debater. He holds a BSc (Hons) in Forensic Biology, an MSc (Research Masters) in Evolutionary Biology, a second MSc in Medical and Molecular Biosciences, and a PhD in Evolutionary Biology. He is currently an Assistant Professor of Biology at Sattler College in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. McLatchie contributes to several apologetics websites and is the founder of Apologetics Academy (Apologetics-Academy.org), a ministry that seeks to equip and train Christians to persuasively defend the faith through regular webinars, as well as to assist Christians struggling with doubt. Dr. McLatchie has participated in over thirty moderated debates around the world with representatives of atheism, Islam, and other alternative worldview perspectives. He has lectured internationally in Europe, North America and South Africa promoting an intelligent, thoughtful and evidence-based Christian faith.

Original Blog: https://cutt.ly/ERkWVCH

Translated by Elias Castro

Edited by Elenita Romero