Este artículo es el quinto de una serie de nueve partes sobre cómo conseguimos nuestra Biblia. En la primera parte se analizó la inspiración y la inerrancia. En la segunda parte se analizó el desarrollo del Antiguo Testamento. La tercera parte examinó el canon del Antiguo Testamento y los apócrifos. En la cuarta parte se examinaron los atributos canónicos de los libros del Nuevo Testamento. En este artículo se explica cómo la Iglesia primitiva recibió el canon del Nuevo Testamento.

Marción (85-160 d.C.)

Antes de entrar en la recepción corporativa del canon, es necesario decir unas breves palabras sobre Marción. Según el historiador de la Iglesia Henry Chadwick, Marción fue “el más radical y para la Iglesia el más formidable de los herejes”[i] ¿Cuál era la herejía de Marción? Promovía el gnosticismo, es decir, la creencia de que el dios que creó el mundo era malo y, por tanto, el AT era malo. Esta creencia llevó a Marción a rechazar todo el AT y la mayoría de las partes del NT que hablan positivamente del AT.

Por lo tanto, el canon de Marción incluía una versión mutilada de Lucas que dejaba fuera todas las referencias positivas al AT, así como cualquier indicio de que Jesús pudiera haber sido realmente un humano físico. El gnosticismo, después de todo, enseñaba que el mundo físico era malo. Jesús, entonces, sólo parecía ser humano -un punto de vista conocido como Docetismo.

La Iglesia rechazó universalmente a Marción. Ningún padre de la iglesia tiene nada remotamente positivo que decir sobre él. De hecho, después de que Marción hiciera una considerable donación a la iglesia de Roma, se la devolvieron tras conocer sus opiniones heréticas.

¿Cuándo recibió la Iglesia el canon?

El llamado canon de Marción sugiere que la Iglesia ya tenía algún tipo de canon funcional a mediados del siglo II. Lo que plantea una pregunta importante: ¿Cuándo recibió la Iglesia el canon del NT? La respuesta a esta pregunta depende en gran medida de cómo se defina el canon. Michael Kruger da tres definiciones:[ii]

Canon exclusivo – La Iglesia solidificó los límites canónicos en el siglo IV.

Canon funcional – Los textos canónicos fundamentales funcionaban con autoridad en el siglo II.

Canon ontológico – Los textos tenían autoridad desde que los apóstoles terminaron de escribirlos.

El resto de este post se centrará principalmente en el canon funcional y un poco en el canon exclusivo. Para más información sobre el canon ontológico, véase el primer artículo de esta serie sobre la inspiración de los textos bíblicos. En ese artículo, llamo la atención sobre el hecho de que los autores bíblicos eran conscientes de que estaban escribiendo una Escritura con autoridad.

La recepción del canon del Nuevo Testamento

En el espacio restante, voy a argumentar que la iglesia reconoció la mayor parte del NT como fidedignoen el siglo II. Posteriormente, la Iglesia afirmó los márgenes del canon en el siglo IV. Para apoyar esta afirmación, consideraré cuatro puntos clave.

- Declaraciones de los Padres de la Iglesia

Varias declaraciones de los padres de la iglesia sugieren que reconocían ciertos textos como autorizados. Ireneo (180 d.C.), por ejemplo, señala: “No es posible que los evangelios puedan ser ni más ni menos que el número que son. Porque como hay cuatro zonas del mundo en que vivimos y cuatro vientos principales… 2025 también los querubines tenían cuatro caras”[iii]. Si bien podemos rascarnos la cabeza ante la lógica de Ireneo, una cosa es segura: él creía que cuatro y sólo cuatro Evangelios tenían autoridad.

Justino Mártir (150 d.C.) también reconoció su autoridad cuando mencionó que la iglesia leía estos textos en el culto comunitario junto al AT. Señala: “Y en el día llamado domingo, todos los que viven en las ciudades o en el campo se reúnen en un lugar, y se leen las memorias de los apóstoles o los escritos de los profetas, siempre que el tiempo lo permita”[iv]. Nadie cuestiona que la iglesia primitiva reconociera la autoridad del AT. El hecho de que leyeran textos del NT junto con el AT sugiere que creían que ambos eran Escrituras.

Ignacio (110 d.C.) reconoce la autoridad de los apóstoles frente a la suya cuando dice: “No os mando como Pedro y Pablo. Ellos fueron apóstoles, yo estoy condenado”[v]. Ignacio fue un influyente líder eclesiástico en el siglo II. Pero incluso él reconoció que los escritos de Pedro y Pablo estaban en un nivel totalmente distinto al suyo.

Al examinar detenidamente los primeros padres de la iglesia, encontrarás varias citas que hacen referencia a la autoridad de los textos del NT.

- Apelación a los textos como si fueran la Escritura

Los primeros padres de la Iglesia no sólo afirman que los textos del Nuevo Testamento eran fidedignos, sino que también apelan a ellos como Escrituras de inspiración divina. La Epístola de Bernabé (130 d.C.), por ejemplo, utiliza la fórmula “está escrito” cuando cita el Evangelio de Mateo. Es bien sabido que los autores del NT emplean con frecuencia esta fórmula cuando citan un texto del AT. La Epístola de Bernabé dice: “Como está escrito: Muchos son los llamados, pero pocos los escogidos”[vi].

Policarpo (110 d.C.) hace una referencia aún más explícita. Señala: “Como está escrito en estas Escrituras: “Airaos, pero no pequéis; no se ponga el sol sobre vuestro enojo”[vii]. Curiosamente, Policarpo cita dos textos y se refiere a ambos como “Escritura”. El primer texto era el Salmo 4:5, y el segundo era Efesios 4:26.

De hecho, entre mediados y finales del siglo II, unos cuantos padres de la Iglesia conocidos apelan a un conjunto básico de libros canónicos, indicando que creían que esos libros eran de hecho Escritura. Ireneo apela a los siguientes libros como Escritura:

Mateo, Marcos, Lucas, Juan, Hechos, Romanos, 1 Corintios, 2 Corintios, Gálatas, Efesios, Filipenses, Colosenses, 1 Tesalonicenses, 2 Tesalonicenses, 1 Timoteo, 2 Timoteo, Tito, Hebreos, Santiago, 1 Pedro, 1 Juan, 2 Juan y Apocalipsis.[viii]

Sólo faltan Filemón, 2 Pedro, 3 Juan y Judas.

Igualmente, Clemente de Alejandría apela a los siguientes libros como Escritura:

Mateo, Marcos, Lucas, Juan, Hechos, Romanos, 1 Corintios, 2 Corintios, Gálatas, Efesios, Filipenses, Colosenses, 1 Tesalonicenses, 2 Tesalonicenses, 1 Timoteo, 2 Timoteo, Tito, Filemón, Hebreos, 1 Pedro, 1 Juan, 2 Juan, Judas y Apocalipsis.[ix]

Sólo faltan Santiago, 2 Pedro y 3 Juan.

Alrededor del año 250 d.C., Orígenes nos da una lista canónica completa en su homilía sobre Josué. Fíjate bien en todos los libros a los que hace referencia:

Pero cuando viene nuestro Señor Jesucristo, cuya llegada designó aquel anterior hijo de Nun, envía a los sacerdotes, sus apóstoles, portando “trompetas martilladas”, la magnífica y celestial instrucción de la proclamación. Mateo hizo sonar primero la trompeta sacerdotal en su Evangelio; Marcos también; Lucas y Juan tocaron cada uno sus propias trompetas sacerdotales. Incluso Pedro grita con trompetas en dos de sus epístolas; también Santiago y Judas. Además, Juan también toca la trompeta a través de sus epístolas 2025, y Lucas, al describir los Hechos de los Apóstoles. Y ahora viene el último, el que dijo: “Creo que Dios nos muestra a los apóstoles en último lugar”, y en catorce de sus epístolas, tronando con trompetas, derriba los muros de Jericó y todos los artificios de la idolatría y los dogmas de los filósofos, hasta los cimientos[x].

Notarás que Orígenes atribuye a Pablo catorce cartas en lugar de trece. La explicación más probable de este error es la creencia común de que Pablo escribió el libro de Hebreos.

- Evidencia de los manuscritos

Uno de los mejores indicios de que los libros del NT funcionaban con autoridad en los siglos II y III es la cantidad de manuscritos existentes que tenemos en nuestro poder. En este momento, tenemos más de sesenta manuscritos del NT de los siglos II y III. El Evangelio de Juan es el que más tiene, con dieciocho. Mateo es el segundo con doce. En comparación, tenemos diecisiete manuscritos de los siglos II y III de todos los textos apócrifos combinados. En otras palabras, tenemos más manuscritos de Juan que de todos los libros apócrifos juntos. El texto apócrifo con más manuscritos es el Evangelio de Tomás, que tiene tres.

La cantidad de manuscritos existentes indica qué libros utilizaba la iglesia con más frecuencia. Juan y Mateo fueron aparentemente los dos libros más populares en la iglesia primitiva, según el número de manuscritos existentes que poseemos. El hecho de que casi no tengamos manuscritos apócrifos indica que la Iglesia primitiva no los utilizaba mucho.

También hay que destacar el hecho de que todos los manuscritos del Nuevo Testamento de los siglos II y III están en formato de códice (precursor de los libros modernos). Ninguno está en un pergamino. Dicho esto, el pergamino era la forma de libro más popular de los siglos II y III. Con el tiempo, a medida que el cristianismo crecía, el códice se convirtió en la forma de libro dominante en el mundo antiguo.

Aunque ninguno de los textos del Nuevo Testamento está en un pergamino, los textos apócrifos sí lo están. Además, como el códice permitió a la Iglesia colocar cómodamente varios libros en un solo códice, tenemos varios códices con múltiples Evangelios y cartas de Pablo. El P46, por ejemplo, es una colección de nueve cartas de Pablo. El P75 contiene Lucas y Juan. P45 es un códice con cuatro Evangelios. No tenemos ningún códice que combine los evangelios canónicos y los apócrifos. En otras palabras, ningún manuscrito tiene Mateo, Marcos, Lucas, Juan y Tomás. Los manuscritos nos dicen todo lo que necesitamos saber sobre los libros que la iglesia primitiva consideraba autorizados.

- Listas canónicas

En 1740, Lodovico Antonio Muratori publicó una lista en latín de los libros del NT conocida como el Fragmento Muratoriano. Este fragmento contiene una lista canónica temprana que la mayoría remonta a la iglesia del siglo II en Roma. El canon incluye los siguientes libros:

Mateo, Marcos, Lucas, Juan, Hechos, Romanos, 1 Corintios, 2 Corintios, Gálatas, Efesios, Filipenses, Colosenses, 1 Tesalonicenses, 2 Tesalonicenses, 1 Timoteo, 2 Timoteo, Tito, Filemón, 1 Juan, 2 Juan, Judas y Apocalipsis.

Sólo faltan Hebreos, Santiago, 1 Pedro, 2 Pedro y 3 Juan. Esta lista, junto con las listas de los primeros padres de la iglesia, indica que la iglesia del siglo II reconoció un grupo central de libros canónicos a mediados o finales del siglo II. Sólo faltan algunos libros marginales. Con el paso del tiempo, la iglesia acabó afirmando el canon de veintisiete libros que tenemos hoy.

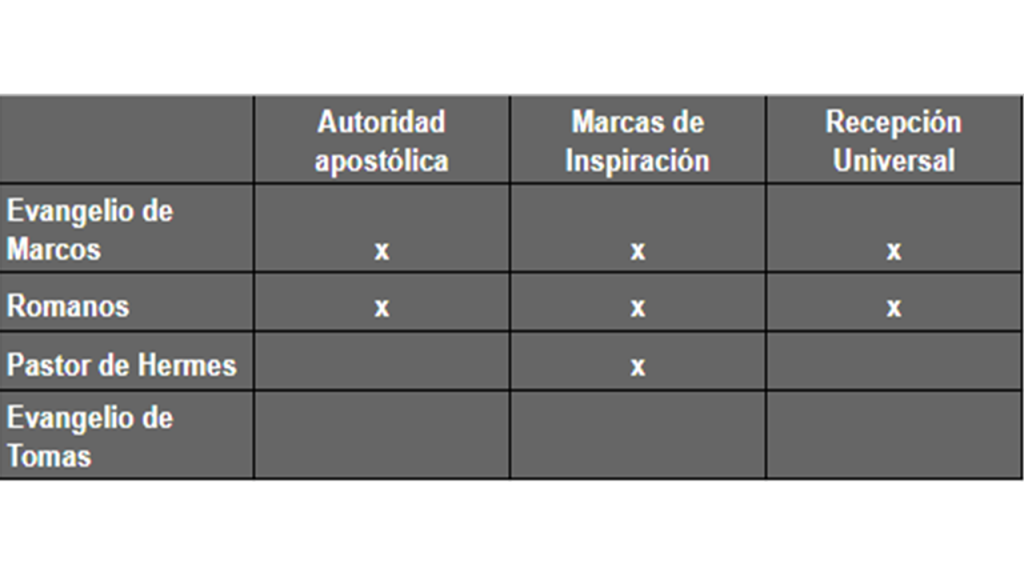

Alrededor del año 320, el historiador de la Iglesia Eusebio dio una lista canónica que subdividió en cuatro categorías:[xi]

Libros reconocidos: Eusebio señala que estos libros eran universalmente aceptados.

Mateo, Marcos, Lucas, Juan, Hechos, Romanos, 1 Corintios, 2 Corintios, Gálatas, Efesios, Filipenses, Colosenses, 1 Tesalonicenses, 2 Tesalonicenses, 1 Timoteo, 2 Timoteo, Tito, Filemón, Hebreos, 1 Pedro, 1 Juan y Apocalipsis.

Libros controvertidos: Eusebio comentó que estos libros eran “discutidos pero conocidos por la mayoría”.

Santiago, 2 Pedro, 2 Juan, 3 Juan y Judas

Libros espurios: Eusebio señala que se trata de libros que la iglesia primitiva consideró útiles, pero que no eran Escrituras.

Hechos de Pablo, Pastor de Hermes, Apocalipsis de Pedro, Epístola de Bernabé, Didajé y Evangelio de los Hebreos

Libros heréticos: Eusebio dice que estos libros han sido universalmente rechazados.

Evangelio de Pedro, Evangelio de Tomás, Hechos de Andrés, Hechos de Juan y Evangelio de MatíasObsérvese que entre los libros reconocidos y los controvertidos que eran “conocidos por la mayoría”, está presente todo el canon del Nuevo Testamento. También vale la pena señalar que Eusebio creía que los libros heréticos eran totalmente repulsivos. Considere sus palabras:

Nos hemos sentido obligados a dar este catálogo para que podamos conocer tanto estas obras como las que son citadas por los herejes bajo el nombre de los apóstoles, incluyendo, por ejemplo, libros como los Evangelios de Pedro, de Tomás, de Matías, o de cualquier otro además de ellos, y los Hechos de Andrés y Juan y de los otros apóstoles, que nadie perteneciente a la sucesión de escritores eclesiásticos ha considerado digno de ser mencionado en sus escritos. Y además, el carácter del estilo está en desacuerdo con el uso apostólico, y tanto los pensamientos como el propósito de las cosas que se relatan en ellos están tan completamente fuera de acuerdo con la verdadera ortodoxia que claramente se muestran como ficciones de los herejes. Por lo tanto, no deben ser colocados ni siquiera entre los escritos rechazados, sino que todos ellos deben ser desechados como absurdos e impíos.

En otras palabras, no fue que estos libros “casi” entraron en el canon. El canon no se redujo a una votación arbitraria. La iglesia rechazó estos libros desde muy temprano debido a su naturaleza diabólica.

Siguiendo a Eusebio, Atanasio dio una lista canónica completa con los veintisiete libros en el año 367. En los años 393 y 397, los concilios de Hipona y Cartago también afirmaron los veintisiete libros en el canon.

Reconocido No determinado

Para terminar, quiero aclarar un punto importante. La iglesia no concedió autoridad a ningún texto del NT. Se limitó a reconocer los libros que ya tenían autoridad en la iglesia. Como dice J. I. Packer, “La Iglesia no nos dio el canon del Nuevo Testamento como Sir Isaac Newton no nos dio la fuerza de la gravedad. Dios nos dio la gravedad… Newton no creó la gravedad, sino que la reconoció”.

En el próximo post, pasaremos a la preservación del texto del NT. En concreto, examinaremos la tradición de los manuscritos y la crítica textual.

Notas de pie de página:

[i] Henry Chadwick, The Early Church, 39.

[ii] Michael Kruger, The Question of Canon, 29-46.

[iii] Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3.11.8.

[iv] Justin Martyr, First Apology, 67.3.

[v] Ignatius, Romans. 4:4.

[vi] Epistle of Barnabas 4.14.

[vii] Polycarp, Philippians, 12.1.

[viii] Michael Kruger, Canon Revisited, 228.

[ix] Michael Kruger, The Question of Canon, 168.

[x] Origen, Homily on Joshua 7.1.

[xi] Eusebius, Church History, 3.25.1-7.

Recursos recomendados en Español:

Robándole a Dios (tapa blanda), (Guía de estudio para el profesor) y (Guía de estudio del estudiante) por el Dr. Frank Turek

Por qué no tengo suficiente fe para ser un ateo (serie de DVD completa), (Manual de trabajo del profesor) y (Manual del estudiante) del Dr. Frank Turek

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Ryan Leasure tiene un Máster en Artes por la Universidad de Furman y un Máster en Divinidad por el Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Actualmente, es candidato a Doctor en Ministerio en el Seminario Teológico Bautista del Sur. También sirve como pastor en Grace Bible Church en Moore, SC.

Fuente Original del blog: https://bit.ly/3Uo2SWG

Traducido por Jennifer Chavez

Editado por Mónica Pirateque