By Terrell Clemmons

It’s Time to Remit Darwinian Storytelling to the Annals of History.

Stephen Meyer was a young geophysicist working in the oil industry in Dallas, Texas, in 1985 when he saw that an interesting science conference was coming to town and he decided to drop in. During a panel discussion on the origin of the first living things, Charles Thaxton, a highly credentialed chemist, noted that the information stored in DNA could not be explained by chemical evolutionary processes. This was generally known already and uncontroversial. But Thaxton ventured a step further by suggesting that the information could point to an intelligent cause. This was a reasonable inference, Thaxton said because, in our regular human experience, we know that information is typically attributable to intelligent causes.

This struck Meyer as both intuitive and plausible. But what really piqued his interest was the heated reaction of some of the other scientists at this suggestion. They got really personal. Some criticized Thaxton’s intellect; others, his motives, as if he’d broken some unwritten convention. What was with all this emotion? Meyer wondered. He’d always thought scientists were objective professionals who coolly looked at data and followed the evidence. This was an interesting problem.

The encounter led to some follow-up discussions with Thaxton and a burning new question, which Meyer would take with him to Cambridge University a year later: Could this idea of intelligence—or intelligent design—be made into a rigorous scientific argument?

But during his first year there, an after-lecture social gathering brought home a sobering reality. Everyone at Cambridge was openly atheistic. In fact, atheism was so preemptively the assumed worldview that theism was not even on the table. Meyer not only believed in God; he was a Christian. Clearly, this could be a lonely work environment, and the widespread atheism around him could present obstacles to collaborations on this question. But he took heart in remembering the great scientists of history whose science had been specifically driven by their Christian worldview.

The Closed Darwinian Circle

Science writer Tom Bethell, who had arrived at sister university Oxford about twenty-five years prior, experienced a similarly disappointing revelation. He’d arrived at Oxford “naively imagining that philosophy taught us the meaning of life.” It didn’t.

But Bethell later came to see its usefulness. Many problems in philosophy had flourished, he discovered, because the words used to formulate theories weren’t clearly defined. Sometimes, he further realized, the vagaries seemed to be intentional. Bethell would go on to a long career as a philosophically astute journalist, brilliantly clarifying and parsing some of the most crucial enigmas of public life and history.

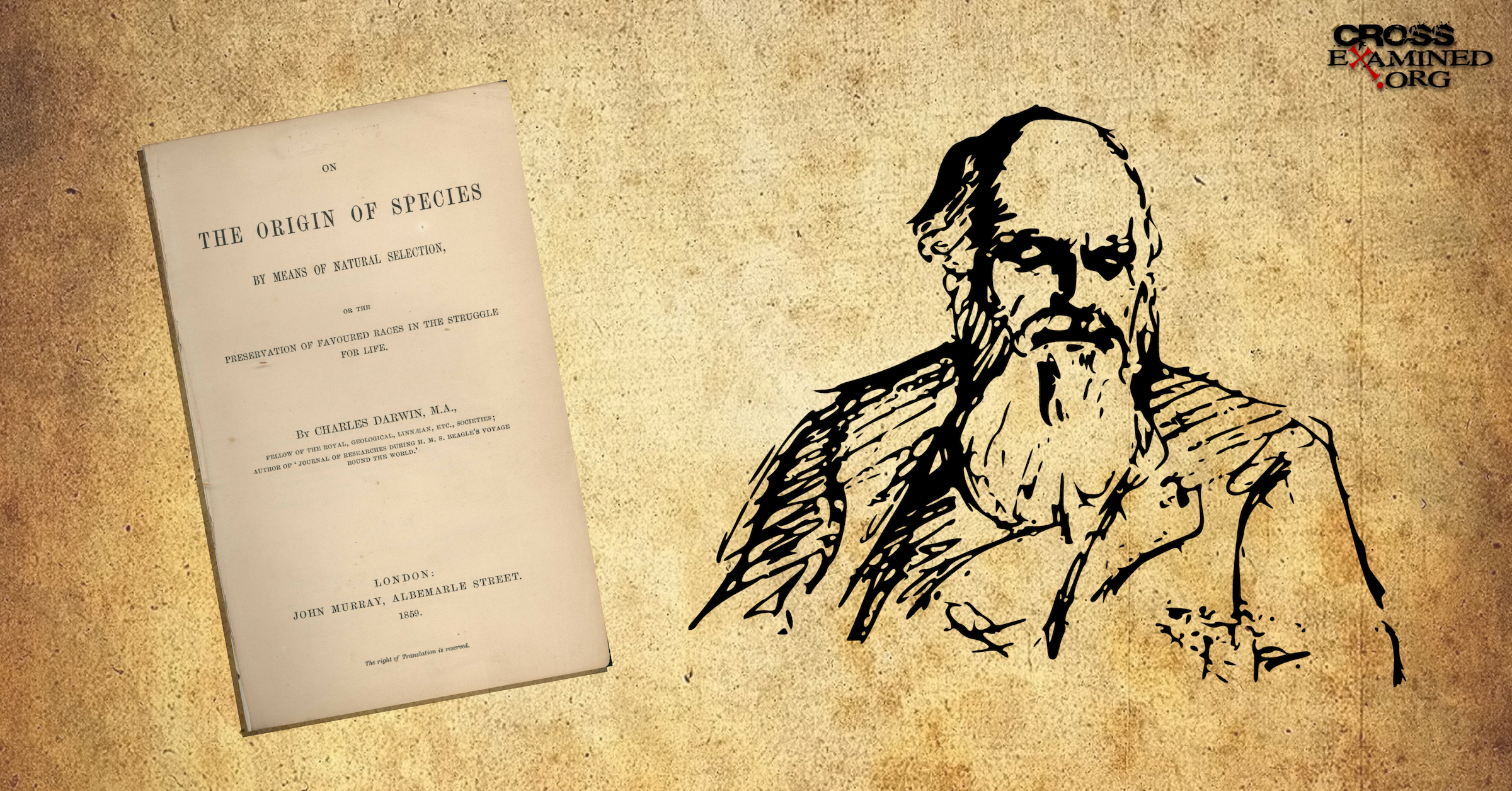

Case in point: Charles Darwin’s central postulate said that the diversity of biological life on earth could be explained by natural selection operating on random variations. Herbert Spencer, a contemporary of Darwin, summarized this notion as “survival of the fittest.” The phrase stuck, and today, Darwin’s postulate reigns as the grand unifying theory of established science.

But was there an inherent problem with it, philosophically, from the very start? “Doubts about evolution first arose in my mind when I looked at the title page of The Origin of Species,” Bethell wrote.

I read, and then reread that page:

On the Origin of Species

by Means of Natural Selection

or the

preservation of favoured races

in the struggle for life

by Charles Darwin, M.A.

1859

The words ‘preservation’ and ‘favoured’ stood out. Was there any way of knowing what ‘races’ (meaning species, or individual variants) were favored other than by looking to see which ones were in fact preserved?

This was no pedantic quibble. For if there truly is no way of determining what is “fit” other than by seeing what survives, then Darwin was arguing in a self-confirming circle: the survival of the survivors. In rhetorical terms, this is what’s called a tautology—a statement that is true by definition, due to the construction of the language by which it is expressed. In effect, Darwin’s proposed mechanism—natural selection—rested on the observation that, “Survivors survive.” To which any clear-thinking middle-school student might say, “Well, duh.”

Curating History

Beginning with this observation, Bethell’s latest book examines the dialogue that has taken place among scientists since the publication of The Origin. But rather than giving us a chronological point-counterpoint synopsis of it, Bethell presents a kind of “tour” of the topics over which the debate has been hashed out—the “rooms,” if you will, of the 150-plus-year-old house of Darwin: common descent, natural selection, the fossil record, information theory, evolutionary psychology, artificial intelligence, the growing intelligent design movement, and more.

The upshot of it all is captured in his title: Darwin’s House of Cards: A Journalist’s Odyssey Through the Darwin Debates. Darwinism is an idea past its prime, he concludes, one whose collapse is inevitable and is in fact already demonstrably underway.

Examining a Theory and Its Theorist

He states that forthrightly, but also backs it up with characteristically sound logic—examining, like a museum curator, Darwin’s various claims in light of both mounting new evidence against them and the ongoing lack of evidence supporting them. Room by room, he shows how evolutionary theory today is being propped up by logical fallacies, bogus claims, and outdated empirical evidence that has all but disintegrated under the weight of new discoveries.

In addition to covering the high points of the scientific discussion, Bethell also delves into the man Darwin as he revealed himself through his personal writings. While Darwin was in his own right a legitimate scientist, his theorizing was influenced, inordinately as it turns out, by three ideas of his day: Malthusian economics, Progress, and philosophical materialism.

- Malthusian Math: Political economist Thomas Malthus had speculated that when population growth outstrips food supply, then death by starvation would result in some sectors of society but not others. Darwin had read Malthus, and he simply transferred the calculus of overpopulation to the plant and animal kingdom. “It at once struck me that under these circumstances favorable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavorable ones to be destroyed. The result would be the formation of new species.” Darwin had no evidence of the formation of any new species, though. That was pure extrapolation.

- Progress: Capitalized to denote the philosophy as it existed in his day, “Progress” was the reigning metanarrative in post-Enlightenment England, the all-encompassing, assumed a trajectory of reality. It was “as difficult for him to escape as the air he breathed,” wrote Bethell, and Darwin was a confirmed believer. The word “evolution” doesn’t actually appear in The Origin. He referred rather to improvement, progress, and perfection, in the end, writing that “all corporeal and mental endowments will tend to progress toward perfection.”

- Materialism: Darwin himself was a full-blown materialist, but he avoided outwardly confessing the extent of his belief. He’d worked out his theory by 1837, but didn’t go public with it for more than twenty years, partly because the 1830s climate of opinion was highly unfavorable to materialism. Even at publication in 1859, he still didn’t deploy it consistently in The Origin, but rather strategically and progressively invoked it over the course of six editions.

Darwin’s metaphysical outlook was not a deduction from his science, though, but was influenced by his theology. He raised theological issues in several of his writings, and Bethell devotes an entire chapter to his evolving religious views. Two points are worth mentioning here. In his autobiography, Darwin mentioned being “heartily laughed at” for quoting the Bible while on the H.M.S. Beagle. We can only speculate about the psychological effect of this incident, but it obviously affected him enough to write about it forty years later. Afterward, he reconsidered the Bible’s place in his view of the world and concluded it was “no more to be trusted than the sacred books of the Hindoos, or the beliefs of any barbarian.”

In addition, like many in insulated societies, he took issue with God over the problem of evil and suffering, ultimately deciding that the concept of an all-loving and all-powerful God could not be reconciled with the reality of misery in the world. “Thus disbelief crept over me at a very slow rate, but was at last complete.”

More a product of their theorist and the zeitgeist, then, than of science, Darwin’s postulates found easy acceptance among an elite intelligentsia predisposed to believe in materialism and Progress. Sadly, liberal clergy went along without objection or concern.

Straightening Out Bad Philosophy

Molecular biologist Jonathan Wells concurs with Bethell that Darwinian evolution is one long argument bolstering an a priori metaphysics. In Zombie Science: More Icons of Evolution, he gives three common definitions of science: (1) empirical science is the enterprise of seeking truth by formulating hypotheses and testing them against evidence; (2) technological science comprises the advances that have enriched modern life; and (3) establishment science consists of professionals conducting research. These can all be legitimate uses of the word.

In addition, though, he notes, some people have come to define science as (4) the enterprise of providing natural explanations for everything. But this would more accurately be called methodological naturalism. And while it is true that the methods of empirical science limit the causal explanations, it can confirm or disconfirm to the material realm, to go further and assume that only material causes exist is to assume an unstated claim about metaphysical reality. Furthermore, to do so and call it science constitutes fraud.

Metaphysical Storytelling & the Judgment of History

Fraud aside, it also compromises science. When priority is given to proposing and defending materialistic explanations over following the evidence, materialistic philosophy is running the show. Where this happens (and it does), Wells calls it zombie science. “Evolution is a materialistic story,” he writes, “and since the materialistic story trumps the evidence, it is zombie science.”

Listen to biologist-turned-filmmaker Randy Olsen’s explanation for why he knowingly passed off falsehood in his 2007 film Flock of Dodos: The Evolution-Intelligent Design Circus: “Scientists must realize that science is a narrative process, that narrative is story; therefore science needs story.” This is stunning! What Olson is saying here is that metaphysical storytelling should override accuracy in science reporting.

Returning to Meyer at Cambridge, during his first year, he was granted a second telling revelation when his supervisor offered some unsolicited advice. “Everyone here is bluffing,” the kindly old school don said. “And if you’re to succeed, you must learn to bluff too.”

Fortunately, Meyer opted for personal integrity and legitimate science over bluffing and storytelling and then left it to others to sort things out. Imagine the exhibit in some future Museum of Science and History: Everyone believed the Darwinists, boys, and girls until a few brave scientists concerned with data and following evidence came along and called their bluff.

That, ladies and gentlemen, is a science story worth telling.

Terrell Clemmons is a freelance writer and blogger on apologetics and matters of faith.

This article was originally published at salvomag.com: http://bit.ly/2z72XqW