How to Disagree Better about COVID-19, Conspiracy Theories, and Pretty Much Everything Else in Life

Aside from feeling the fatigue of quarantine in general, I am feeling the fatigue of people arguing about the quarantine. This includes Christians fighting with other Christians, Christians fighting with non-believers, and non-believers fighting with non-believers.

If you spend any time on social media, you know exactly what I’m talking about.

Our culture has largely lost the ability to disagree well. I’ve experienced this for years when discussing worldview issues with both Christians and skeptics. But because these worldview conversations tend to take place in online pockets, the nature of those disagreements isn’t always front and center in public life. The universal experience of COVID-19 right now, however, has shone a light on just how poorly many people conduct disagreements—for all to see. And what I see happening in COVID-19 disagreements is the same thing I’ve so often seen happen in worldview disagreements:

People don’t know how to have disagreements at the right level.

Let me explain.

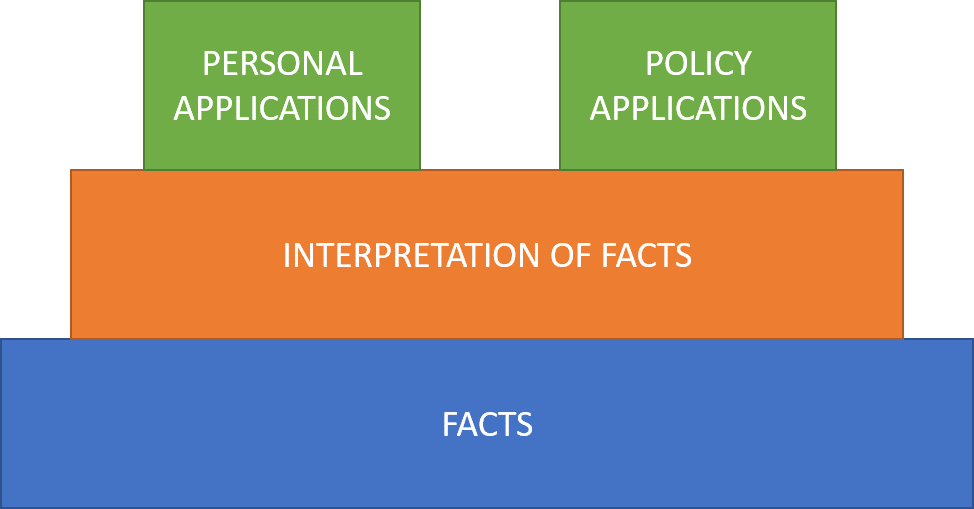

Facts, Interpretations of Facts, and Applications of Interpretations (the FIA Pyramid)

A simple example will demonstrate the problem with many disagreements, as well as the power of using what I’m going to call the FIA thought pyramid: Facts, Interpretations of Facts, and Applications (both personal and policy).

Let’s say I came downstairs this morning and found stuffing from my puppy’s bed all over the floor. There are holes in her bed, and a little stuffing hanging from the corner of her mouth. Those are facts (and a true story!).

I then interpret this to mean that my puppy made a hole in the bed and pulled stuffing out. I didn’t actually see it happen, but I’ve inferred from the facts that this was the case.

Based on this interpretation, I’m upset with her and decide something must change (a personal application).

I then make a new rule (a policy application) that she is not allowed to have a bed of this kind until she has outgrown her puppy months.

Now, imagine that I’ve cleaned all this up before my kids have even opened their eyes for the day. When they eventually make it downstairs, they see I’ve taken the puppy’s bed away. Here’s how they process the situation:

- Fact: Mommy took the puppy’s bed away.

- Interpretation: Mommy is mean.

- Personal application: I’m mad at mommy.

- Policy application: The new rule is unfair.

This situation could lead to a giant tug of war between my kids and me if we chose to argue over the policy application (the fairness of the new bed rule):

Them: “It’s so unfair! She needs her bed!”

Me: “It’s perfectly fair. She isn’t old enough to have one like this.”

But the central disagreement here isn’t over the rule. It’s over the facts. In this case, the kids have a missing fact. They didn’t know that the puppy destroyed her bed this morning. Yes, we could all agree that mommy took the bed away (one fact), but the additional fact that she destroyed her bed and was harmfully eating stuffing was missing. If I shared with the kids what happened, so they now had that additional information, their new thought pyramid could quickly change to this:

- Fact: Mommy took the puppy’s bed away because she was eating from it and could hurt herself.

- Interpretation: Mommy is trying to protect the puppy.

- Personal application: Mommy can be trusted to make good decisions for the puppy.

- Policy application: The new rule is fair.

In this example, there was initially disagreement at the top of the pyramid (policy application) because the kids were working from an incomplete set of facts. (This isn’t the only kind of fact problem in the real world, of course; people can have different sets of facts, different types of facts, different numbers of facts, and inaccurate “facts” spread throughout their working knowledge of something.) Because of this, it would be pointless to debate the new rule in and of itself. We needed to work backward in the pyramid to see where the real disagreement was and have a conversation at that level.

Now that we’ve seen a simple example let’s look at disagreement at various places on the pyramid with COVID-19.

Disagreement Over Facts

When it comes to COVID-19, it’s fair to say that NO ONE knows all the facts because it’s a new virus. Most of us, as non-specialists in epidemiology, glean what we know from a variety of sources online, and those sources vary in credibility. Oftentimes what we believe is a fact is really an interpretation of other facts. With the massive amount of new data available, and different people trusting different sources, we are bound to have significant disagreements with one another at the fact level. Yet, most arguments I see happen are at the policy level: continued lockdown or no continued lockdown.

This is a hopeless argument if you haven’t taken the time to consider the FIA thought pyramid.

Imagine, for example, that person one is working from this pyramid:

- Fact: The number of deaths to date this year is no different than the number of deaths to date in prior years.

- Interpretation: COVID-19 is no different from the flu.

- Personal application: Not worried about catching COVID-19.

- Policy application: Lockdowns aren’t warranted and are destroying the economy.

Now imagine that person two is working from this pyramid:

- Fact: The number of deaths to date this year significantly exceeds the number of deaths to date in prior years.

- Interpretation: COVID-19 is responsible for most of those additional deaths.

- Personal application: COVID-19 is something we should all be very concerned about.

- Policy application: Lockdowns are necessary to save lives.

These two people could angrily argue over whether lockdowns are necessary, but it would be a waste of breath (or typing). They are working from different assumed facts, and likely won’t agree on policy applications because of it. It’s entirely possible that if they agreed on the facts, they would agree on the policy as well and wouldn’t even be having the discussion. That said, there’s not a direct path from facts to policy, either. In the middle, we have to consider interpretations of facts.

Disagreement Over Interpretation of Facts

Let’s say now that these two people are working from the same set of assumed facts, but they’re still arguing over lockdown vs. no lockdown. It’s possible they disagree at the level of interpretation.

Perhaps the person one is working from this thought pyramid:

- Fact: The number of deaths to date this year significantly exceeds the number of deaths to this date in prior years.

- Interpretation: The additional deaths still aren’t extreme.

- Personal application: Not very worried about catching COVID-19.

- Policy application: Lockdowns aren’t warranted and are destroying the economy.

And perhaps person two is working from this thought pyramid:

- Fact: Ditto person 1.

- Interpretation: COVID-19 is responsible for a tragic increase in death worldwide.

- Personal application: COVID-19 is something that we should all be very concerned about.

- Policy application: Lockdowns are necessary to save lives.

In this case, our two people could agree that there are more deaths this year (and even that they’re due to COVID-19), but interpret the severity of that increase very differently. One person might see a 20% increase in deaths as minimal, whereas another might see it as devastating. That interpretation can make all the difference in how one views policy decisions.

Disagreement Over Applications of the Interpretations

Let’s say now that these two people are working from the same set of assumed facts and interpretations, but they’re still arguing over lockdown vs. no lockdown. It’s possible they disagree at the level of applications (personal and/or policy).

Now person one is working from this thought pyramid:

- Fact: The number of deaths to date this year significantly exceeds the number of deaths to this date in prior years.

- Interpretation: The additional deaths still aren’t extreme.

- Personal application: Has major underlying risk factors and is very concerned about any COVID-19 exposure.

- Policy application: Doesn’t believe lockdowns are warranted for everyone (will take personal measures to protect him/herself but thinks lockdowns overall are destroying the economy).

Meanwhile, person two is working from this thought pyramid:

- Fact: Ditto person 1.

- Interpretation:Ditto person 1.

- Personal application: Ditto person 1.

- Policy application: Believes lockdowns are warranted for everyone to save lives.

In this example, the two people could both personally be at risk and feel very concerned about their own well-being, but have very different opinions on how that relates to policy for everyone else. You could also have a person two who doesn’t have risk factors and isn’t personally concerned (personal application level), but believes lockdowns are the most compassionate policy for people like person 1—even though person one him/herself disagrees! Personal and policy applications don’t always go hand-in-hand.

How to Disagree Better in 3 Easy Steps

So, where does this leave us? We can disagree better in three “easy” steps.

- Ask good questions to determine where the disagreement lies.

When you disagree with someone, remember this FIA pyramid (Facts, Interpretations, and Applications). There’s a really good chance that if you’re arguing about policies or politics in general, you have a disagreement at a more fundamental level. Ask the other person to clarify exactly what they’re advocating for, why they’re advocating for it, and what led them to the conclusion that they should advocate for it. Then compare that to your own FIA pyramid (do some soul searching to figure out what that looks like!) and identify where the departure in the agreement is.

- Engage in the appropriate conversation for the level where the disagreement lies.

If you realize the disagreement is over facts, responding with how you interpret the facts you’re using is typically not going to move the conversation forward. You should instead be discussing data sources, whom to trust, why to trust them, and so on.

Or, if you find that you agree on facts and interpretations but have a difference of opinion on policy application, then you should be discussing things like desired policy outcomes and why there’s good reason to believe a given policy leads to those outcomes. In other words, it’s not enough to identify where the disagreement lies; the ensuing conversation should reflect that level as well.

- Don’t be a jerk.

Wherever you and another person are disagreeing on the FIA pyramid, there’s just never a reason to treat someone else poorly. This should be obvious. Question facts, interpretations, and applications—don’t attack people or groups of people who have a thought pyramid different than your own. Seek understanding and respond with love and humility.

Recommended resources related to the topic:

Tactics: A Game Plan for Discussing Your Christian Convictions by Greg Koukl (Book)

Practical Apologetics in Worldview Training by Hank Hanegraaff (Mp3)

The Great Apologetics Adventure by Lee Strobel (Mp3)

Defending the Faith on Campus by Frank Turek (DVD Set, mp4 Download set and Complete Package)

So the Next Generation will Know by J. Warner Wallace (Book and Participant’s Guide)

Reaching Atheists for Christ by Greg Koukl (Mp3)

Living Loud: Defending Your Faith by Norman Geisler (Book)

Fearless Faith by Mike Adams, Frank Turek and J. Warner Wallace (Complete DVD Series)

Natasha Crain is a blogger, author, and national speaker who is passionate about equipping Christian parents to raise their kids with an understanding of how to make a case for and defend their faith in an increasingly secular world. She is the author of two apologetics books for parents: Talking with Your Kids about God (2017) and Keeping Your Kids on God’s Side (2016). Natasha has an MBA in marketing and statistics from UCLA and a certificate in Christian apologetics from Biola University. A former marketing executive and adjunct professor, she lives in Southern California with her husband and three children.

Original Blog Source: https://bit.ly/2Bd8xMn

![Copy of [JORGE] – OFFICIAL SIZE (Podcast) Do not resize!](https://crossexamined.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Copy-of-JORGE-OFFICIAL-SIZE-Podcast-Do-not-resize.jpg)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!