The Legacy of Herod & the Impact of Jesus in History

Part 2

King Jesus

In my previous article “A Take of Two Kings: Part 1 – King Herod,” I presented an overview of the life and legacy of Herod I, (also known as Herod the Great.) Herod was declared King of Judea by the Roman senate in 40 B.C. He left behind a legacy of violence, bloodshed, great political ambition, as well as the archaeological ruins of some truly remarkable buildings still visible today.

When one thinks of Herod, he is usually remembered as a king, even if he was a very bad king, yet Jesus of Nazareth was also a king. When most people think of Jesus today, however, they usually don’t think of Him as a king. Not only was Jesus of Nazareth a king, He was THE King of all kings and Lord of all lords.

As in the previous article on Herod, we will explore some very important questions about one of the most influential lives to ever walk the earth – the life and impact of Jesus since His birth, death and resurrection.

What exactly was the lineage of Jesus, and why does it matter? If Jesus was a king, then where did He get His authority? Did the Bible predict His coming thousands of years before He was born? How did Jesus impact history, and why does His life continue to affect millions around the world to this day? Does the Bible predict that Jesus will return to earth to reign as King over the nations?

Background of Jesus’ Early Life and Times

Herod the Great is remembered today as an accomplished builder. Jesus was also a builder – a carpenter. Having been reared by Joseph as an apprentice carpenter, it is very likely that Jesus could have even been a stone mason. A couple of reasons why this was so, was because of the abundance of limestone which was used as a primary building material in the first-century, and the fact that just outside of Nazareth archaeologists have uncovered the fascinating city of Sepphoris.

In 3 B.C., Herod Antipas (Herod’s son) made Sepphoris the site of his new capital of the Galilee region. At its height, Sepphoris reached a population of thirty thousand people! Jesus, along with Mary & Joseph, grew up right near this thriving city. It is very likely then, that Joseph & Jesus would have worked as stone-cutters or builders for the many construction projects that were certainly happening in Sepphoris.[1]

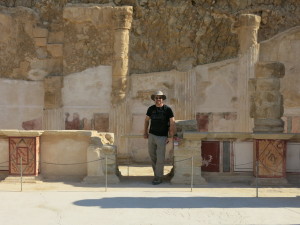

Cardo (road) at Sepphoris

The discovery of Sepphoris by archaeologists has given scholars an interesting insight into the boyhood, youth and profession of Jesus.

In addition, New Testament scholar, Craig Evans writes:

The proximity of this city to the village of Nazareth, where Jesus grew up, and the presence of a number of highways, cautions against the assumption that Jesus and His fellow Galileans were placebound and unacquaninted with the larger world.[2]

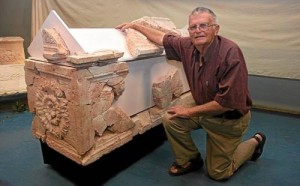

Even though archaeologists have not excavated any physical buildings or structures that Jesus built, they have discovered many of the places, people and structures that Jesus visited and conducted His ministry. One of the most interesting of these is the small village of Capernaum located on the Sea of Galilee.

Capernaum was just a small fishing village in Jesus’ day, yet it served as the base of His ministry in the Galilee region (Matthew 4:12-17 & Mark 2:1). In Matthew 9:1 He even called it His, “own city.”

At the site today are the remains of two archaeologically and historically significant structures. One is the floor of a first-century Jewish synagogue in which Jesus walked, taught, and performed miracles (see Mark 1:21ff).

The ruins of the first-century synagogue today are covered by the ruins of a 4th Century synagogue built on top of the floor of the earlier one (see image below)

Synagogue at Capernaum

The other structure at Capernaum is a group of edifices that cover something called the Insula Sacra (a Latin phrase which refers to a group of homes around a central courtyard).

Based on archaeological and historical evidence, including pottery, coins and inscriptions found on site, Franciscan archaeologists believe they have found the home of Simon Peter, the fisherman who became a disciple of Christ and one of the main leaders of the early church along with James, Jesus’ half-brother.[3]

Over the ruins of Peter’s house is an octagonal shaped structure – a basilica which dates to the middle of the fifth century A.D.

Ruins of the 5th Cent. Basilica at Capernaum – built over the house of St. Peter

According to archaeologist, Jack Finegan:

There is little doubt that it is the church of which the Anonymous of Piacenza reported in A.D. 570: ‘We came to Capernaum into the house of St. Peter, which is a basilica.’[4]

These remains, as well as many others, illuminate the life and ministry of Jesus of Nazareth and provide independent confirmation, apart from the Gospels themselves of the authenticity and trustworthiness of the New Testament.[5]

Jesus’ Authority & Lineage as Israel’s King

Herod’s rise to political power ultimately came from imperial Rome. But unlike Herod’s lineage as rightful king of Judah, Jesus’ lineage and authority, can be traced back before the foundations of time and history itself.

The Micah 5:2 passage, which is oft quoted during the Christmas season, gives insight into this.

But you, Bethlehem Ephrathah, though you are little among the thousands of Judah, yet our of you shall come forth to Me the One to be Ruler in Israel, whose goings forth are from old, from everlasting

In the garden of Eden, Eve was promised by God, “[a Son] who would crush the head of the serpent” (Gen. 3:15b). This is the very first mention of the Gospel (evangelion – good news) in the Bible. Theologians often call this the proto-evangelion (or first Gospel). The reason why it was good news is because of the episode with the serpent in Genesis 3 which brought sin and death to the world. God told Adam and Eve that essentially He would not leave them in that state of affairs (i.e. in a fallen state), but would restore them and destroy the works of the serpent through someone (Jesus) who would come from body the woman.

For thousands of years, the history of Old Testament Israel was filled with prophecies, foreshadowings, images, and metaphors of Israel’s coming king, and anointed One (Messiah). During those intervening years before Jesus came, two pictures emerged of Messiah from the Law, the Prophets and the Writings: one was a Suffering Servant, and the other, a conquering King. When Jesus came the people of Israel paid attention only to the Old Testament passages which referred to their coming King as a great conquerer and warrior – like King David. They paid little or no attention to the passages which speak of their King coming to suffer and bear the sins of the world.

The Son of David

In Matthew’s Gospel, Matthew traces Jesus’ genealogy back to Abraham and David (Matthew 1:1-17). Abraham was the father of the Jewish nation and embodies all of Israel’s hopes, ideals and future (Genesis 12; 15; 22). Without the connection to Abraham, Jesus would have been an imposter. Abraham is foundational.

Jesus’ lineage is also traced back to the Old Testament king David. Why David? Because nearly 1000 years before Jesus was born a promise (a covenant) was given to David that one of his descendants would sit on the throne in Jerusalem and that the Kingdom would never come to an end (2 Samuel 7:12-16).

To David God said:

When your days are fulfilled and you rest with your fathers, I will set up your seed after you, who will come from your body, and I will establish his kingdom. He shall build a house for My name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. …and your house and your kingdom shall be established forever before you, Your throne shall be established forever (2 Sam. 7:12-13, 16)

Since that original promise to David in about 1000 B.C., the promise has echoed down through the Old Testament prophets and saints pointing to a future ruler and king who would one day be born. These prophecies would contain detailed information on what the king would do, and what he would be like. In the 8th Century B.C. (700’s) the prophet Isaiah predicted the birth of a son who would have the characteristics that only God has:

For unto us a Child is born, Unto us a Son is given; And the government will be on His shoulder, and His named will be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the increase of His government and peace There will be no end, Upon the throne of David and over His kingdom, to order it and establish it with judgment and justice from that time on and forever. The zeal of the Lord of hosts will accomplish this (Isaiah 9:6-7)

Perhaps one of the most remarkable passages in the Old Testament which was written 700 years before Christ was born was Isaiah 53. Isaiah 53 speaks of a certain person who would be stricken down and endure great suffering. The reason for the suffering? Verse 5 gives the reason:

But He was wounded for our transgressions, He was bruised for our iniquities; The chastisement for our peace was upon Him and by His stripes we are healed.

The passage goes on to describe that this suffering servant of God would be buried in a rich man’s grave.

And they made His grave with the wicked – but with the rich at His death, because He had done no violence, nor was any deceit in His mouth (v. 9)

When Jesus was crucified and buried these verses as well as many other prophecies were literally fulfilled – including the Micah 5:2 prophecy predicting where Israel’s promised King would be born – in Bethlehem.

The Resurrection of Jesus

Throughout Jesus’ public ministry He directly and indirectly made the claim that He indeed was the One true King, who was promised and predicted in the Old Testament. Early in the ministry of Jesus, John the Baptist sent word to Jesus asking,

“Are You the Coming One, or do we look for another?” Jesus answered and said to them, ‘Go and tell John the things which you hear and see: The blind see, the lame walk; the lepers are cleansed and the deaf hear; the dead are raised up and the poor have the gospel preached to them. And blessed is he who is not offended because of Me’ (Matthew 11:3-6).

When he heard these words, John the Baptist would have immediately understood that Jesus was indeed the promised One, because all of the things Jesus mentioned were predicted by the Old Testament centuries earlier.

Throughout His life Jesus’ words and works were a strong testimony to who He claimed to be – namely God, yet the one thing that provided the stamp of authenticity on His identity was His resurrection from the dead.

Jesus’ Legacy

According to Acts 1:9-11 Jesus ascended into heaven after appearing to His disciples as well as many others.

Before He departed, He told His disciples:

But you shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be witnesses to Me in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth (Acts 1:8)

One of the most lasting and enduring legacies of Jesus Christ – apart from securing eternal salvation from sin – was and still is His people – the Church.

To the church was given Christ’s message of good-news that God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, so that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have everlasting life (John 3:16).

That message was preached and lived by the early Christians in such a way that in about three centuries nearly the entire Roman world had access to the Gospel.

It would be difficult to measure the full impact of Christ’s life since He walked the earth. Perhaps that impact can somewhat be measured by the devotion of His followers to be salt and light in the world as they were commanded by Christ Himself (Matthew 5:13-16).

Paul Copan has documented some of the achievements of Christ’s followers in the two millennia since He lived:

- The Eradication of Slavery (from the Roman period until now)

- Opposition of Infanticide (common in Greece & Rome)

- The Elimination of gladiatorial games (outlawed in the 4th Cent.)

- The Building of Hospitals and Hospices

- The Elevation of Women’s Rights & Status

- Founded Europe & North America’s great universities

- The Writing of Extraordinary works of literature (Dante, Milton, etc…)

- Creation of beautiful artistic masterpieces (Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Gothic cathedrals, etc..)

- Established modern science (from the notion that the world was created by a rational, orderly God)

- Composition of brilliant musical works (Bach, Handel, Hayden, etc…)

- Advocating human rights (concern for the poor, human dignity rooted in the truth that people are made in God’s image)[6]

Indeed as Copan summarizes here:

It’s difficult to exaggerate the impact that Jesus of Nazareth has had on history and the countless lives impacted by this one man’s life and teaching – indeed, the transforming power of the cross and resurrection. The historian Jaroslav Pelikan remarked that by changing the calendar (to BC and AD according to the “Year of our Lord”) and other ways, “everyone is compelled to acknowledge that because of Jesus of Nazareth history will never be the same.[7]

[1] For more on this, see Craig Evans, Jesus and His World: The Archaeological Evidence (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2012), pp. 13-37.

[2] Ibid.

[3] for detailed information on this see, Jack Finegan’s, The Archaeology of the New Testament: The Life of Jesus and the Beginnings of the Early Church (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), pp. 107-11.

[4] See Finegan, pp. 110-11.

[5] For additional information see John McRay’s, Archaeology & the New Testament

[6] Paul Copan, Is God a Moral Monster? Making Sense of the Old Testament God (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2011), pp. 218-19.

[7] Ibid., 219.