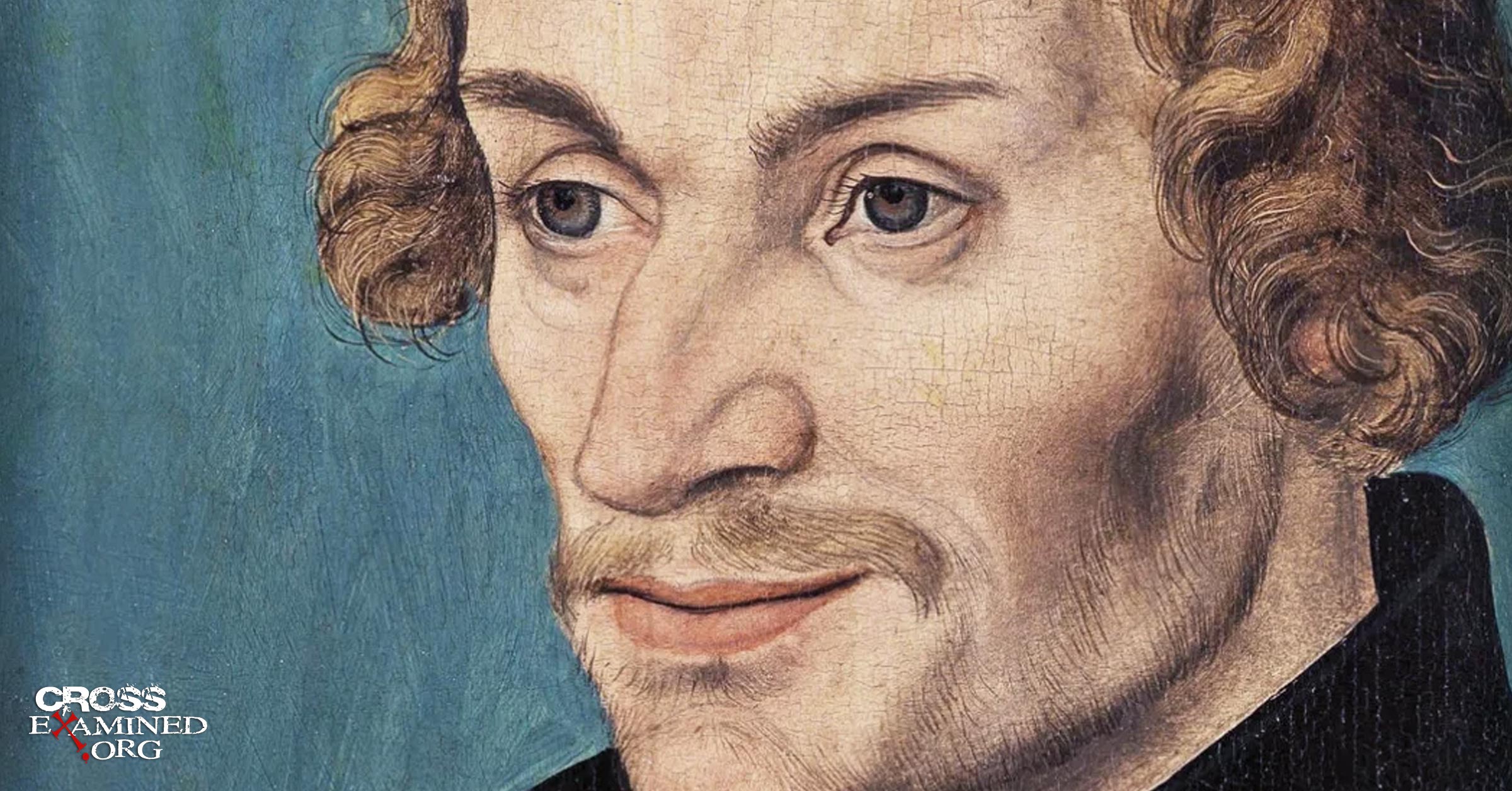

Missing Melanchthon

Recently I have been accused of “historical eisegesis.”[1]

According to Wikipedia, “eisegesis is the process of interpreting text in such a way as to introduce one’s own presuppositions . . . It is commonly referred to as reading into the text.” This is definitely a problem when someone does this when reading Scripture, but it’s never a compliment to be accused of this in any context.

The context of this accusation is regarding my book, Human Freedom, Divine Knowledge, and Mere Molinism. After surveying Luther, Calvin, and Philip Melanchthon, I concluded that the original Reformers were quite open to the concept of “limited libertarian freedom.” That is to say, although they might have rejected libertarian freedom when it comes to soteriological matters, they seemed to affirm the libertarian freedom to make choices regarding issues not related to salvation.

Indeed, the eminent Reformed scholar Richard Muller has reached similar conclusions in his book, Divine Will and Human Choice (p 222-223):

“Not a few of the proponents and critics of the Reformed doctrine of free choice and divine willing have confused the specifically soteriological determination of the Reformed doctrine of predestination with a ‘divine determinism of all human actions.”

Although I am not the first to point this out, the charge of “historical eisegesis” seems to have been lodged against me alone which left me scratching my head. How could anyone reach this conclusion after reading multiple quotes from the great Reformers I shared in my dissertation/book? One quote from Melanchthon particularly stood out to me. Although I thought Luther and Calvin were clear enough, if there were still any doubt, the great systematic theologian of the Reformation made it clear that humans seem to possess the freedom, opportunity, and categorical ability to do otherwise (libertarian freedom) in mundane matters not related to soteriology (salvation). Indeed, it is my favorite quote from the historical survey. Here is how it reads in my dissertation submitted to North-West University (also found on pg. 111 of my book):

Melanchthon (1521b:151)—the acknowledged theologian to Lutheranism—explains Luther’s position more thoroughly:

“Nor, indeed, do we deny liberty to the human will. The human will has liberty in the choice of works and things which reason comprehends by itself. It can to a certain extent render civil righteousness or the righteousness of works; it can speak of God, offer to God a certain service by an outward work, obey magistrates, parents; in the choice of an outward work it can restrain the hands from murder, from adultery, from theft. Since there is left in human nature reason and judgement concerning objects subjected to the senses, choice between these things, and the liberty and power to render civil righteousness, are also left…. Therefore, although we concede free will the liberty and power to perform the outward works of the Law, yet we do not ascribe to free will these spiritual matters, namely, truly to fear God, truly to believe God, truly to be confident and hold that God regards us, hears us, forgives us, etc.” [151].

Following this quote, I included one more from Melanchthon which seems to seal the deal. In fact, this is my favorite quote from any Reformer because he seems to be explicitly clear in describing libertarian freedom noting that we have power to choose or choose otherwise:

In another place Melanchthon (1521b:151) says: “You yourself have experienced that it is in your power to greet or not to greet him, to put on this coat or not put it on, to eat or not to do so…. By contrast, internal affections are not in our power.”

If that does not sound like the limited libertarian freedom to choose or choose otherwise, I’m not sure what does.

After reading the words of the Reformed systematic theologian, how could anyone accuse me of “historical eisegesis?” Indeed, it seems to me that anyone reading the Reformers in their own words and reaching a different conclusion could be accused of the same. After contemplating this charge, I went to my book and was met with horror . . . Melanchthon’s key quote somehow did not make the final cut!

I have no idea how this happened. One of the most important and key quotes from my dissertation did not make it to my book for some reason (I am sure I am to blame — or gremlins)! I will rectify this situation in the second edition of my book. I’m currently working on a “Mere Molinism Study Guide” (which will be published by Wipf and Stock) co-authored with Timothy Fox. We will find a way to include it in the study guide when we write the section on the historical survey. Stay tuned!

Bottom line: There is good reason to believe that the original Reformers, although they rejected the idea of libertarian freedom regarding salvation issues, would also reject the idea of exhaustive divine determinism (EDD). It seems that they affirmed the idea of limited libertarian freedom in external matters (libertarian freedom limited to things unrelated to salvation issues).

Oswald Bayer seems to affirm libertarian freedom in these “external matters.” In fact, he contends that even the unregenerate can freely choose to do “good” things (or not). These “good” choices in the context of the community of the external world are meaningless regarding issues pertaining to salvation. Bayer summarizes the views that Luther, Melanchthon, and the majority of Reformers probably shared:

A human being has the freedom to order his or her own life. He or she carries responsibility for the way in which this occurs. A Christian acts in the realm of worldly justice together with those who are not Christians. In this realm, God preserves the reason and freedom of both Christians and non-Christians.[2]

Bayer (along with multiple other scholars) vindicates me from the charge of historical eisegesis.[3] Moreover, and more importantly, if Bayer is right about the beliefs of the original Reformers regarding limited libertarian freedom, and the Reformers also believed that an omniscient God knows these limited libertarian free choices logically prior to the divine creative decree and that God is still sovereign over these libertarian choices, then the original Reformers were “mere Molinists” whether they realized it or not!

Stay reasonable (Isaiah 1:18),

Dr. Tim Stratton

Notes

[1] Guillaume Bignon, A critical review and fairly comprehensive refutation of “Human Freedom, Divine Knowledge, and Mere Molinism” by Timothy A. Stratton, http://www.associationaxiome.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Response-to-Tim-Stratton.pdf. See my 50-page response here: Bignons’ Review of Mere Molinism: A Rejoinder.

[2] Freedom? The Anthropological Concepts in Luther and Melanchthon Compared Author(s): Oswald Bayer Source: The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 91, No. 4 (Oct.,1998), pp. 373-387 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Harvard Divinity School Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1509856 Accessed: 08-03-2018 20:23 UTC (Pg 385)

[3] Consider the words of Shedd (a Reformed systematic theologian) who affirms the sourcehood libertarian freedom of Adam:

“In respect to its having no sinful antecedent out of which it is made, sin is origination ex nihilo. Sin is the beginning of something from nothing, and there is this resemblance between it and creation proper. In holy Adam, there was no sinful inclination or corruption that prompted the first transgression. Adam started the wicked inclination itself ex nihilo, by a causative act of self-determination.”

William Greenough Thayer Shedd, Dogmatic Theology, ed. Alan W. Gomes, 3rd ed. (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R Pub., 2003), p. 521

Recommended resources related to the topic:

How to Interpret Your Bible by Dr. Frank Turek DVD Complete Series, INSTRUCTOR Study Guide, and STUDENT Study Guide

How Philosophy Can Help Your Theology by Richard Howe (MP3 Set), (mp4 Download Set), and (DVD Set)

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Timothy A. Stratton (Ph.D., North-West University) is a professor at Trinity College of the Bible and Theological Seminary. As a former youth pastor, he is now devoted to answering deep theological and philosophical questions he first encountered from inquisitive teens in his church youth group. Stratton is the founder and president of FreeThinking Ministries, a web-based apologetics ministry. Stratton speaks on church and college campuses around the country and offers regular videos on FreeThinking Ministries’ YouTube channel.

Original Blog Source: https://cutt.ly/0vF2wLd