The Book of Acts is High-Resolution Reportage Part 1

The book of Acts is one of the most fascinating books of the Bible. No other book matches its level of historical corroboration from both internal and external sources. The abundant evidence, that we shall sample in this essay, of Luke’s credibility and meticulousness as a historian, indirectly supports the credibility of Luke’s gospel (which is widely acknowledged to be written by the same author).

Luke claims to have been a travelling companion of Paul for much of his travels (Acts 16-10-17 and later again from Acts 20:5, travelling with Paul as far as Rome). This places Luke in Jerusalem in Acts 21 when Paul visited the Jerusalem leaders. Luke tells us that “all the elders [including James] were present” (Acts 21:18). Luke also implies that he remained in proximity to Paul during his two-year imprisonment in Caesarea Maritima, since he presents himself as being with Paul both immediately before and immediately after this imprisonment. During this time, Luke would undoubtedly have had ample access to the many living witnesses to Jesus’ resurrection, since Caesarea is only approximately 120 kilometers from Jerusalem, or about two to three days journey on foot (where many of the witnesses to Jesus’ resurrection resided). Luke’s acquaintance with the Jerusalem apostles thus puts him in a position to know what was being proclaimed concerning the nature and variety of the post-resurrection encounters with Jesus. Luke’s demonstrated care and meticulousness as an historian (together with the fact that he put his own neck on the line for the gospel) also provides some reason to think that Luke is sincerely representing what he believes the apostles experienced. Furthermore, various specific aspects of Luke’s gospel can be historically corroborated, which confirms that Luke, more than merely having access to those eyewitnesses of Jesus’ life, faithfully represented the testimony of those eyewitnesses. And yet, Luke represents the post-resurrection encounters as involving multiple sensory modes. Jesus appears to multiple individuals at once, and those encounters are not merely visual but are also auditory. Jesus engages the disciples in group conversation. The encounters are close-up and involve physical contact (Lk 24:39-40). At least one encounter involved passing Jesus a broiled fish (Lk 24:41-43). According to Acts 10:41, the disciples ate and drank with Jesus after his death. Jesus engages with Cleopas and his companion in an extended discourse, even participating with them in a study of the Scripture (Lk 24:27). Moreover, Acts indicates that the appearances were spread out over a forty-day time period – thus, the resurrection encounters were not one brief and confusing episode (Acts 1:3). Acts also contributes to the case that the disciples maintained an ongoing leadership role within the early church despite the hostile context of persecution (see my essay here for a fuller discussion of this subject). This evinces the sincerity of the apostles.

Moreover, given Luke’s access to Paul, together with his track-record of historical scrupulousness, this provides reason to think that Luke accurately represents Paul’s own testimony concerning his conversion and miracles. This argues strongly against the plausibility of Paul being sincerely mistaken. Indeed, Paul’s experience is alleged to have been multisensory — involving both a visual and auditory component (Acts 9:3-6, 22:6-10, 26:13-18; 1 Cor 9:1, 15:8). Moreover, it was intersubjective — affecting not only Paul, but also his travelling companions who were purportedly thrown to the ground, having heard the voice though seeing no one (Acts 9:7, 22:9; 26:14). Acts 22:9 indicates that Paul’s travelling companions nonetheless saw the light. Moreover, Paul was blinded by the experience for three days (Acts 9:8-9; 22:11) and later healed by Ananias who received a vision concerning Paul, and Paul a vision concerning Ananias (Acts 9:10-19; 22:12-16).

Furthermore, Paul claims to have performed miracles. In 2 Corinthians 12:12, he writes, “The signs of a true apostle were performed among you with utmost patience, with signs and wonders and mighty works,” (cf. Rom 15:18-19).[i] Note that this appeal is made to an audience who had in their midst individuals who doubted Paul’s apostolic credentials. It was risky to appeal to such miracles if there were no such convincing miracles to speak of that could be brought to the minds of his critics. Though Paul does not indicate what those signs purportedly involved, we read in Acts about the sort of miracles that Paul performed. For example, Luke describes a curse that Paul placed on the magician Elymas (who had opposed Paul and Barnabas, seeking to turn the Proconsul away from the faith) where Paul caused him to go blind on command, a feat apparently so convincing that it led to the conversion of the proconsul Sergius Paulus (Acts 13:9-12). Among Paul’s other miraculous signs, he healed a man who had been crippled since birth (Acts 14:8-10), cast out a spirit of divination from a slave girl (Acts 16:16-18), experienced a miraculous jailbreak in Philippi (Acts 16:25-26), healed many sick (Acts 19:11-12), raised Eutychus from the dead after his fall from the third story of a building (Acts 20:9-12), and healed the father of Publius, who lay sick with fever and dysentery, on Malta (Acts 28:7-9). As we shall see in this article, Luke was an incredibly scrupulous historian who had a high regard for historical accuracy. He also valued eyewitness testimony (Luke 1:2). The most probable source for the alleged miracles in Acts (besides those that he might have witnessed himself) is Paul.

When we consider the content of Paul’s testimony concerning his conversion experience on the Damascus road, together with his purported miracles, it seems to be difficult to account for on the supposition that he was sincerely mistaken — in particular, given that he was not already predisposed to expect an appearance from the raised Christ. The argument for the reliability of Acts is also relevant to our assessment of the plausibility that Paul was a deceiver. Given Paul’s willingness to endure dangers, hardships, sufferings, floggings, beatings, stoning, shipwrecks, imprisonment and martyrdom, over an extended period of time, on account of the gospel (as abundantly documented by Acts), this goes a long way towards establishing his sincerity.

Thus, the book of Acts is of significant value to two of the major arguments for Christianity — namely, Jesus’ resurrection and the conversion and miracles of the apostle Paul.

The Focus of This Article

In 1791, the English clergyman William Paley published a book titled Horae Paulinae, or the Truth of the Scripture History of St. Paul Evinced. Therein, he postulated a class of evidence that he called “undesigned coincidences,” which he applied principally to the historicity of the book of Acts and the authenticity of the thirteen epistles attributed to Paul. Paley summarized the argument as follows:

In examining, therefore, the agreement between ancient writings, the character of truth and originality is undesignedness; and this test applies to every supposition; for, whether we suppose the history to be true, but the letters spurious; or, the letters to be genuine, but the history false; or, lastly, falsehood to belong to both—the history to be a fable, and the letters fictitious: the same inference will result—that either there will be no agreement between them, or the agreement will be the effect of design. Nor will it elude the principle of this rule, to suppose the same person to have been the author of all the letters, or even the author both of the letters and the history; for no less design is necessary to produce coincidence between different parts of a man’s own writings, especially when they are made to take the different forms of a history and of original letters, than to adjust them to the circumstances found in any other writing. [ii]

Putting this into plainer language: When we look at how ancient writings line up with each other, the best evidence of their credibility is if the agreements between them appear to be incidental, casual, and unplanned. We have no less than thirteen letters attributed to the apostle Paul, which make contact with the history recorded in Acts at dozens of points. The epistles are, therefore, fertile ground for this type of analysis.

The focus of this article is the argument from undesigned coincidences, though recognizing that the examples provided in the text that follows are only a sample of the total that could be provided. In particular, I am limiting my dataset to only four of Paul’s letters — that is, his epistle to the Romans, his two epistles to the Corinthians, and that to the Galatians. As we shall see, even with this very limited dataset, and excluding the various striking coincidences that exist between Acts and 1 Thessalonians, or Colossians, or Ephesians, or the Pastoral epistles, one can adduce no less than forty undesigned coincidences between Acts and the Pauline corpus. The examples discussed below quite exhaustive of all those, of which I am aware, in those four letters. I have, however, excluded those coincidences that are relevant only to establishing the authenticity of epistles attributed to Paul (whether widely accepted or disputed) but which do not bear on the credibility of Acts. My hope is that this survey should give the reader a taste of just how extensive this class of evidence is in confirming the historicity of Acts.

Independence of Acts and the Epistles

The undesigned coincidences between Acts and Paul’s letters are even more evidentially significant than those between the gospels, since a strong case can be developed that Luke was not dependent upon the epistles (nor vice versa). Most likely, Luke had not read any of Paul’s letters. This means that, even in those instances where a coincidence is more direct than most of the cases to be discussed here, one may still have confidence that the coincidence is undesigned on the basis of the independence of the sources.

In this section, I shall lay out the evidence that Acts is independent from Romans, the Corinthian letters, and Galatians. One consideration that bears on the broad independence between Acts and these letters is that, though we can pinpoint quite precisely within Acts when these letters were composed (particularly Romans and the Corinthian epistles), Acts makes no mention whatever of Paul writing any epistles. In what follows, I will present a case for independence between Acts and each individual letter. Some of the points raised in this section will be repeated elsewhere in the article as they are of particular relevance to a given coincidence.

Galatians

A particularly strong case can be mounted for the independence of Acts and Galatians. For example, from reading Acts 9:23-25, one might reasonably come away with the first impression that Paul spent the entire period, which Luke glosses over as “many days,” in Damascus. However, Galatians 1:17 indicates that this time, which Paul informs us was three years in duration, included a journey into Arabia (though we do not know for how long). As Paley observes,

Beside the difference observable in the terms and general complexion of these two accounts, “the journey into Arabia,” mentioned in the epistle, and omitted in the history, affords full proof that there existed no correspondence between these writers. If the narrative in the Acts had been made up from the Epistle, it is impossible that this journey should have been passed over in silence; if the Epistle had been composed out of what the author had read of St. Paul’s history in the Acts, it is unaccountable that it should have been inserted. [iii]

Indeed, the omission in Acts concerning the journey into Arabia is quite surprising if the author of Acts was using Paul’s letter as a source. The accounts, though, are not mutually exclusive. The phrase “many days”, used by Luke in Acts 9:23 is most probably an idiomatic expression denoting an indefinite period of time. The equivalent phrase in Hebrew is used in 1 Kings 2:39, but the next verse indicates that those “many days” encompassed a three year period. It is also not particularly implausible that Luke simply was not aware of the journey into Arabia, or for some other reason chose not to write about it (perhaps it was too brief for Luke to consider it to be of significant note). Nonetheless, the apparent discrepancy between Acts and Galatians provides internal evidence of independence between the two sources. Paley offers another piece of evidence indicating independence:

The journey to Jerusalem related in the second chapter of the Epistle (“then, fourteen years after, I went up again to Jerusalem”) supplies another example of the same kind. Either this was the journey described in the fifteenth chapter of the Acts, when Paul and Barnabas were sent from Antioch to Jerusalem, to consult the apostles and elders upon the question of the Gentile converts; or it was some journey of which the history does not take notice. If the first opinion be followed, the discrepancy in the two accounts is so considerable, that it is not without difficulty they can be adapted to the same transaction: so that, upon this supposition, there is no place for suspecting that the writers were guided or assisted by each other. If the latter opinion be preferred, we have then a journey to Jerusalem, and a conference with the principal members of the church there, circumstantially related in the Epistle, and entirely omitted in the Acts; and we are at liberty to repeat the observation, which we before made, that the omission of so material a fact in the history is inexplicable, if the historian had read the Epistle; and that the insertion of it in the Epistle, if the writer derived his information from the history, is not less so. [iv]

An additional reason for thinking that Acts and Galatians are independent is that Acts 9:27 indicates that, in Jerusalem, “Barnabas took him [Paul] and brought him to the apostles and declared to them how on the road he had seen the Lord, who spoke to him, and how at Damascus he had preached boldly in the name of Jesus.” Compare this to Galatians 1:18-19: “Then after three years I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas and remained with him fifteen days. But I saw none of the other apostles except James the Lord’s brother,” (emphasis added). On the surface, this appears to be a discrepancy. Of course, “the apostles” could be taken to refer to Peter and James (most scholars, including myself, are of the opinion that Galatians 1:19 identifies James the Lord’s brother as an apostle). We could also take it that Paul uses ‘saw’ to mean ‘conversed with’ or ‘met with,’ not that he did not even see any of the other apostles in a meeting, etc. We sometimes use ‘saw’ in this sense ourselves. One could imagine that perhaps Barnabas and Peter decided that they did not want to set Paul down in front of them like a tribunal and question him, so during that time he stayed, let us suppose, in someone’s home, met with James and Peter, and otherwise for those two weeks he was out talking and debating with Jews in Jerusalem (Acts 9:28-29), and eventually was rushed away due to a plot to kill him. In any case, the surface tension between these texts adds additional support for the thesis of independence.

Romans

Variations in name spelling between Acts and Romans suggest independence. For example, In Acts refers to Πρίσκιλλα (Acts 18:2, 18, 26), whereas Romans uses the form, Πρίσκα (Rom 16:3). Acts refers to Σώπατρος, identified as “son of Pyrrhus, a Berean” (Acts 20:4), whereas Romans calls this individual by the name Σωσίπατρος. Acts refers to a companion of Paul by the name of Σιλᾶς, whereas Romans 16:21 calls him Σιλουανός.

In Romans 15:24, Paul writes, “I hope to see you in passing as I go to Spain, and to be helped on my journey there by you, once I have enjoyed your company for a while.” Though Luke does mention Paul’s intention to visit Rome (Acts 19:21), there is no reference to his intention to visit Spain.

Romans 16:3-4 credits Priscilla and Aquila for risking their necks for Paul’s life, though there is no account in Acts of this episode, even though Priscilla and Aquila are significant figures in Acts 18.

In Romans 16:21-22, Paul sends greetings from those who are with him at the time: “Timothy, my fellow worker, greets you; so do Lucius and Jason and Sosipater, my kinsmen. I Tertius, who wrote this letter, greet you in the Lord. Gaius, who is host to me and to the whole church, greets you. Erastus, the city treasurer, and our brother Quartus, greet you.” These names only partially overlap with the list given in Acts 20:4: “Sopater the Berean, son of Pyrrhus, accompanied him; and of the Thessalonians, Aristarchus and Secundus; and Gaius of Derbe, and Timothy; and the Asians, Tychicus and Trophimus.” Moreover, Gaius of Derbe is most likely a different person from the Gaius mentioned in Romans, since the latter is described as Paul’s host, implying residence in Corinth or the surrounding region of Achaia. This Corinthian identification is strengthened by Paul’s note in 1 Corinthians 1:14 that he had baptized a Gaius there. Given that Gaius was among the most common Roman praenomina (first names), the duplication of the name is unsurprising. Yet this very fact supports the independence of Acts and Romans — had the author of Acts been drawing on Romans, it would be odd for him to list a Gaius from Derbe without connecting him to Corinth, where the Gaius of the epistle is clearly located. A later copyist, by contrast, would have been far more likely to harmonize the two figures by situating Gaius in Corinth rather than in Derbe.

Furthermore, a major theme in Romans, as well as the Corinthian letters, is the collection being prepared for the relief of the saints in Jerusalem, which we shall discuss in more detail later in this article (Rom 15:25-27; 1 Cor 16:1-4; 2 Cor 8:1-24; 2 Cor 9:1-15). Though Acts agrees with the implied order of travel, there is no explicit mention in Acts of fundraising as a purpose of Paul’s travels (though there is a cryptic allusion to it in Paul’s speech before Felix, in Acts 24:17: “Now after several years I came to bring alms to my nation and to present offerings”). If Acts were using Romans, or the Corinthian epistles, as a source, one might expect the collection to be referred to more explicitly in Acts. The omission of any explicit reference to this collection evinces the independence of Acts from the epistles.

The Corinthian Epistles

As mentioned previously, the collection for the relief of the saints in Jerusalem looms large in the Corinthian epistles, but is never explicitly referred to in Acts. 1 Corinthians, like Romans, uses the form Πρίσκα to refer to the individual whom Acts identifies as Πρίσκιλλα (1 Cor 16:19). Moreover, in 1 Corinthians 1:14-17, Paul stresses that he baptized only Crispus, Gaius, and the household of Stephanus. In Acts 18:8, Crispus is mentioned as a convert, though there is no reference to him being baptized by Paul. Apollos is a hugely significant figure in 1 Corinthians 1-4; 16:12, even causing factions within the church in Corinth, such that some were saying “I follow Paul”; others “I follow Apollos”; or “I follow Cephas”; and still others “I follow Christ.” But in Acts 18-24-19:1, Apollos appears only briefly as a learned Alexandrian who ministered in Corinth, though Acts does not mention the divisions he caused.

Various lines of evidence also converge to reveal that Acts and 2 Corinthians are independent. For example, Titus is mentioned throughout 2 Corinthians (2:13; 7:6, 13, 14; 8:6, 16, 23; 12:18), but is nowhere mentioned in Acts. Moreover, the list of Paul’s sufferings in 2 Corinthians 11:23-29 cannot be readily correlated with Acts (though it is by no means mutually exclusive). For example, 2 Corinthians 11:25 indicates that Paul endured three shipwrecks prior to the beginning of Acts 20 (when he wrote 2 Corinthians from Macedonia). Acts does not record any of those shipwrecks, but instead narrates an entirely different one in chapter 27. This presents no problem for Acts, since the author is clearly selective in what events in Paul’s life he recounts. Indeed, As Paley notes, referring to Acts 18-20, “the history of a period of sixteen years is comprised in less than three chapters; and of these, a material part is taken up with discourses.”[v] Moreover, Paul’s time in Tarsus (comprising several years) is skipped almost entirely (Acts 9:29-30; 11:25-26). Paul’s lengthy stay in Iconium is also glossed over very briefly: “So they remained for a long time, speaking boldly for the Lord, who bore witness to the word of his grace, granting signs and wonders to be done by their hands,” (Acts 14:3). Lengthy periods in Antioch are also described only in passing (Acts 11:25-26; 14:27-28).

Moreover, 2 Corinthians 11:32-33 emphasizes the involvement of Aretas IV in the plot to assassinate Paul in Damascus (but mentions no Jewish involvement), whereas Acts 9:23-25 emphasizes instead the involvement of the Jews (but makes no mention of Aretas). Presumably, the conspiracy involved both parties — nonetheless, the apparent discrepancy between these sources points to their independence. Taken cumulatively, it seems near certain that Luke did not use 2 Corinthians as a source for the composition of Acts.

Undesigned Coincidences

In what follows, I shall present no less than forty undesigned coincidences between Acts and these four epistles.

1. Changing Ministry Model

In Acts 18:1-4, Luke tells us that Paul worked during the week with his own hands as a tent-maker with Aquila and Priscilla in Corinth, and went into the synagogue on the Sabbath day to reason with Jews and Greeks. In response to Silas and Timothy’s arrival from Macedonia, he is prompted to change his ministry model. The text says that Paul συνείχετο τῷ λόγῳ, literally, was wholly absorbed in preaching. What prompted this change? It apparently had something to do with Silas’ and Timothy’s arrival from Macedonia. 2 Corinthians 11:7-9 indicates that the brothers who arrived from Macedonia brought with them financial aid (this is further corroborated by Philippians 4:14-16). This apparently enabled him to devote himself more fully to ministry. Again, the accounts fit together in a casual way, that supports the historicity of Acts.

Undesigned coincidences between Acts and 2 Corinthians, such as the one given above, are further strengthened by the observation that there are several reasons to believe, as discussed earlier in this article, that these two sources are independent of one another. As Paley notes, “Now if we be satisfied in general concerning these two ancient writings, that the one was not known to the writer of the other, or not consulted by him; then the accordances which may be pointed out between them will admit of no solution so probable, as the attributing of them to truth and reality, as to their common foundation.”[vi]

2. Baptism of Crispus and Gaius

In 1 Corinthians 1:14-16, Paul writes, “I thank God that I baptized none of you except Crispus and Gaius, so that no one may say that you were baptized in my name. (I did baptize also the household of Stephanas. Beyond that, I do not know whether I baptized anyone else.)” Why did Paul baptize, by his own hands, Crispus and Gaius? William Paley notes that “It may be expected that those whom the apostle baptised with his own hands, were converts distinguished from the rest by some circumstance, either of eminence, or of connection with him.”[vii] As we saw in the preceding discussion, Romans 16:23 indicates that Gaius provided hospitality for Paul and the church — and so had a particularly close connection with Paul. Moreover, according to 1 Corinthians 16:15, “the household of Stephanas were the first converts in Achaia.” Thus, Paul’s letters confirm a special relationship with the two individuals Gaius and Stephanas. But what about Crispus? Acts 18:8 indicates that, while in Corinth, “Crispus, the ruler of the synagogue, believed in the Lord, together with his entire household. And many of the Corinthians hearing Paul believed and were baptized.” Thus, we learn that Crispus was indeed someone of eminence, being the ruler of the synagogue. This illuminates why his household was one of only three households whom Paul baptized by his own hands.

3. Sending Timothy to Corinth

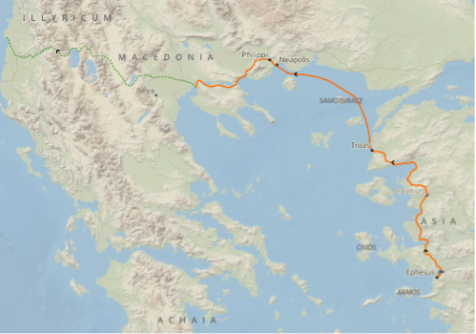

Paul wrote his first letter to the Corinthians while in Ephesus, in around 53 C.E. In 1 Corinthians 4:17, Paul writes, “That is why I sent (ἔπεμψα) you Timothy, my beloved and faithful child in the Lord, to remind you of my ways in Christ…” The verb πέμπω is in the aorist (past) tense, indicating that Timothy has already been sent to Corinth from Ephesus at the time of Paul’s writing. In the account in Acts, however, we read that Timothy was sent, along with Erastus, into Macedonia, though the account in Acts makes no mention of Timothy’s intended destination being Corinth: “Now after these events Paul resolved in the Spirit to pass through Macedonia and Achaia and go to Jerusalem, saying, ‘After I have been there, I must also see Rome.’ And having sent into Macedonia two of his helpers, Timothy and Erastus, he himself stayed in Asia for a while.”

Given Paul’s stated intention to pass through the province of Achaia (where Corinth was the capital), it is a reasonable inference that this was ultimately Timothy’s intended destination, as shown on the map below. Macedonia was on the overland route to Corinth from Ephesus.

However, Acts only records Timothy being sent into Macedonia, since this was his immediate province to which he was directed. Nonetheless, as Paley explains, “One thing at least concerning it is certain: that if this passage of St. Paul’s history had been taken from his letter, it would have sent Timothy to Corinth by name, or expressly however into Achaia.”[viii]

That Timothy went to Macedonia on route to Corinth (and apparently was joined by Paul prior to their going to Corinth) is also supported by 2 Corinthians 1:1, which indicates that Paul and Timothy were co-authors of this second epistle (which, as we shall see later in this article, we have independent reason to believe was written from Macedonia). That Timothy did, in fact, make it to Corinth is also confirmed in an indirect way by Acts 20:4, which lists Timothy as one of those companions who were with Paul upon his departure from Greece.

4. If Timothy Comes

In 1 Corinthians 16:10, we read, “When Timothy comes, see that you put him at ease among you…” The conjunction Ἐὰν introduces the subjunctive mood (literally, “if Timothy comes…”). Even though Paul has already sent Timothy at the time of his writing (indicated by 1 Cor 4:17, as discussed in the preceding section), this indicates that Paul nonetheless expects his letter will arrive first. Timothy must, therefore, have taken a route from Ephesus to Corinth that is less direct than that taken by the letter. The most direct way for Paul to send the letter would be across the Aegean sea, and we would thus infer that Timothy must have gone the indirect, overland route, up through Macedonia (meanwhile Paul remained behind in Ephesus to write 1 Corinthians), as depicted in the map shown previously.

Acts 19:21-22 indicates that Timothy was, in fact, sent from Ephesus to Macedonia, precisely the route we might predict given those subtle clues in 1 Corinthians.

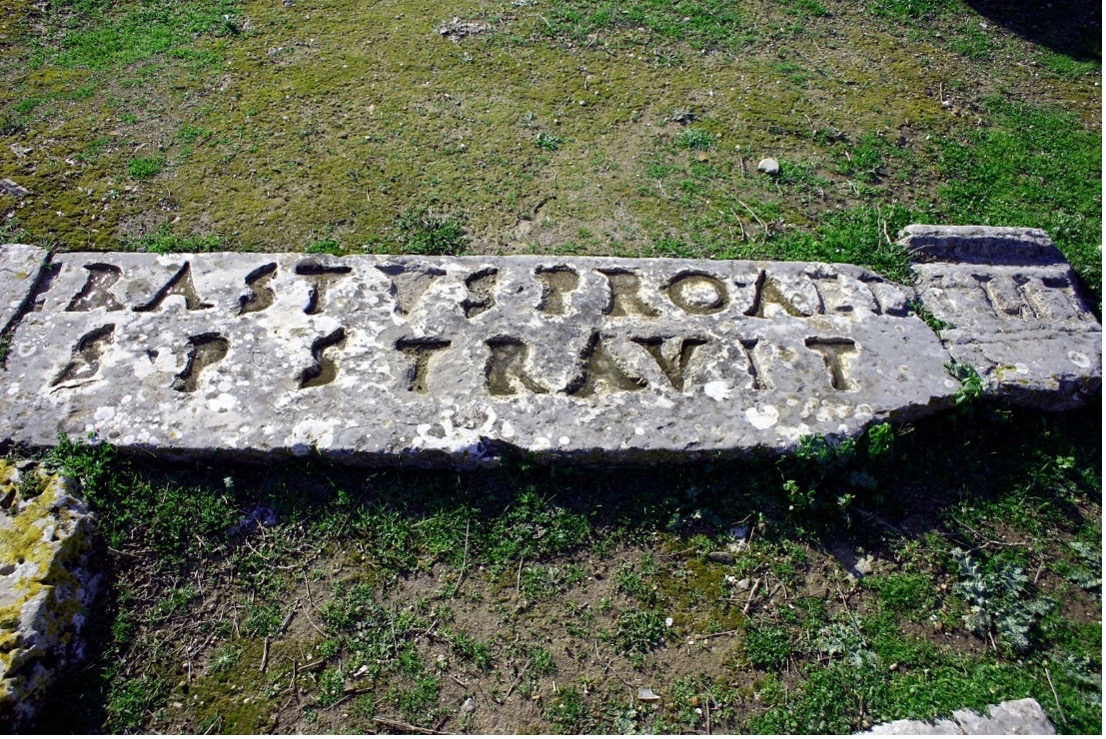

5. Erastus of Corinth

It is also noteworthy to observe that Paul’s travelling companion up through Macedonia, according to Acts 19:22, was Erastus. According to Romans 16:23, Erastus was the city treasurer of the city that Paul was writing from, which we have established on independent grounds to be Corinth. There is even an archaeological discovery, shown below, which confirms the historicity of Erastus — a pavement slab that was recovered from the ruins of ancient Corinth, which bears the inscription in Latin, “Erastus, in return for his aedileship, laid (the pavement) at his own expense.”

The identification of this Erastus with the individual mentioned in the New Testament is disputed, particularly since the inscription calls Erastus aedile, a Roman civic office, whereas the New Testament describes him as the city treasurer. It is plausible, however, that while the inscription commemorates Erastus as aedile, Paul’s epistle reflects him at a later stage of his career, serving as the treasurer of Corinth. Erastus was also not an especially rare name in the Greco-Roman world. Regardless, the primary point I am driving at here does not depend on the identification of the Erastus from the inscription. It is sufficient for our purpose that the epistle to the Romans identifies Erastus as being the city treasurer of Corinth, and hence someone from the city.

How fitting, then, that on his way up through Macedonia with the intention of going to Corinth, Timothy is said to be travelling with an individual whom we know independently was a resident of Corinth.

6. Paul’s Intention to Visit Rome

In his epistle to the Romans, Paul speaks more than once of his desire to visit Rome: “I have often intended to come to you (but thus far have been prevented), in order that I may reap some harvest among you as well as among the rest of the Gentiles,” (Rom 1:13). Again, “But now, since I no longer have any room for work in these regions, and since I have longed for many years to come to you, I hope to see you in passing as I go to Spain, and to be helped on my journey there by you, once I have enjoyed your company for a while…When therefore I have completed this and have delivered to them what has been collected, I will leave for Spain by way of you,” (Rom 15:23-24, 28). Compare this text to Acts 19:21: “Now after these events Paul resolved in the Spirit to pass through Macedonia and Achaia and go to Jerusalem, saying, ‘After I have been there, I must also see Rome.’” Paley remarks,

Let it be observed that our epistle purports to have been written at the conclusion of St. Paul’s second journey into Greece: that the quotation from the Acts contains words said to have been spoken by St. Paul at Ephesus, some time before he set forwards upon that journey. Now I contend that it is impossible that two independent fictions should have attributed to St. Paul the same purpose,—especially a purpose so specific and particular as this, which was not merely a general design of visiting Rome after he had passed through Macedonia and Achaia, and after he had performed a voyage from these countries to Jerusalem. The conformity between the history and the epistle is perfect.[ix]

In the book of Romans, Paul indicates that he has intended often for many years to come visit Rome. In Acts 19:21, we find Paul expressing his desire to visit Rome a considerable time before the composition of this epistle (probably about a year or so prior). Paley further argues that the author of Acts does not appear to have based his account on the epistle to the Romans. In particular,

“If the passage in the epistle was taken from that in the Acts, why was Spain put in? If the passage in the Acts was taken from that in the epistle, why was Spain left out? If the two passages were unknown to each other, nothing can account for their conformity but truth.”[x]

7. The Collection for the Relief of the Saints in Jerusalem

A major theme in Romans and the Corinthian epistles is the collection for the relief of the saints in Jerusalem. The absence of references to this collection in Acts is a major line of evidence that Acts is not textually dependent on these letters. In 1 Corinthians 16:1-4, Paul writes, “Now concerning the collection for the saints: as I directed the churches of Galatia, so you also are to do. On the first day of every week, each of you is to put something aside and store it up, as he may prosper, so that there will be no collecting when I come. And when I arrive, I will send those whom you accredit by letter to carry your gift to Jerusalem. If it seems advisable that I should go also, they will accompany me.” In 16:5ff, Paul indicates that he plans to go to Macedonia and, from there, to travel to the Roman province of Achaia (of which Corinth was the capital city). Paul instructs the Corinthians to have their portion of the collection ready for his arrival.

Paul also mentions this collection in another epistle composed not long before Romans, while in Macedonia: “We want you to know, brothers, about the grace of God that has been given among the churches of Macedonia, for in a severe test of affliction, their abundance of joy and their extreme poverty have overflowed in a wealth of generosity on their part. For they gave according to their means, as I can testify, and beyond their means, of their own accord, begging us earnestly for the favor of taking part in the relief of the saints…” (2 Cor 8:1-4). Thus, at the time of the writing of 2 Corinthians, Paul was apparently in Macedonia, having collected money, and was intending to travel to Corinth from there. We saw previously that 1 Corinthians was composed in Acts 19:22, when Paul remained in Ephesus after sending Timothy through Macedonia. Now we are able to also situate the writing of 2 Corinthians in Acts 20:1, when Paul was in Macedonia. In the following chapter in this letter, he further adds (2 Cor 9:1-5),

“Now it is superfluous for me to write to you about the ministry for the saints, for I know your readiness, of which I boast about you to the people of Macedonia, saying that Achaia has been ready since last year. And your zeal has stirred up most of them. But I am sending the brothers so that our boasting about you may not prove empty in this matter, so that you may be ready, as I said you would be. Otherwise, if some Macedonians come with me and find that you are not ready, we would be humiliated – to say nothing of you – for being so confident. So I thought it necessary to urge the brothers to go on ahead to you and arrange in advance for the gift you have promised, so that it may be ready as a willing gift, not as an exaction.”

Thus, Paul advises the Corinthians that he has been bragging about them to the Macedonians, and that he intends to bring some people from Macedonia with him to Corinth — and he would not want them to be ashamed by not having their portion of the offering ready for his arrival.

While in Macedonia, Paul wrote to the Romans: “At present, however, I am going to Jerusalem bringing aid to the saints. For Macedonia and Achaia have been pleased to make some contribution for the poor among the saints at Jerusalem. For they were pleased to do it, and indeed they owe it to them. For if the Gentiles have come to share in their spiritual blessings, they ought also to be of service to them in material blessings,” (Rom 15:25-27). Paul apparently wrote this letter when he had finished gathering a collection from Macedonia and Achaia and was intending to deliver the funds to Jerusalem. Thus, we can situate the writing of Romans to Acts 20:3, when Paul spent three months in Corinth (in Achaia). In 1 Corinthians, Paul is not sure whether he himself will be in charge of escorting the money to Jerusalem (1 Cor 16:4), though this matter appears to have been resolved by the time he wrote Romans (Rom 15:25).

This order of travel adduced from Romans and the Corinthian epistles comports perfectly with the order of travel reported by Acts, though fund raising is not mentioned there as the purpose of Paul’s journey. Paul’s intended itinerary is given in Acts 19:21: “Now after these events Paul resolved in the Spirit to pass through Macedonia and Achaia and go to Jerusalem, saying, ‘After I have been there, I must also see Rome.’” Notice that all of the placements of the letters within Acts are adduced from clues that relate to the collection Paul is gathering, which is never explicitly mentioned in the book of Acts. According to Acts 21:17ff, Paul arrived in Jerusalem, and Paul was taken into custody by Roman soldiers and imprisoned (v. 27ff). While giving a speech before the Roman procurator of Judea, Felix, Paul makes a cryptic and indirect allusion to this collection: “Now after several years I came to bring alms to my nation and to present offerings.”

8. Representatives of the Gentile Churches

Relating to the preceding example, let us now turn to Acts 20:1-4, which provides the longest list in the book of Acts of companions of Paul all traveling somewhere at the same time:

After the uproar ceased, Paul sent for the disciples, and after encouraging them, he said farewell and departed for Macedonia. 2 When he had gone through those regions and had given them much encouragement, he came to Greece. 3 There he spent three months, and when a plot was made against him by the Jews as he was about to set sail for Syria, he decided to return through Macedonia. 4 Sopater the Berean, son of Pyrrhus, accompanied him; and of the Thessalonians, Aristarchus and Secundus; and Gaius of Derbe, and Timothy; and the Asians, Tychicus and Trophimus.

The respective locations of the individuals listed here are very carefully noted together with their names. It is quite plausible that these various individuals are intended as representatives of the various gentile churches who were contributing to the collection that Paul was gathering at this time for the relief of the saints in Jerusalem. We see throughout Paul’s letters that he desires that everyone know that he is blameless about money and has no agenda of extorting people. This is a major theme in the Corinthian epistles in particular. In 1 Corinthians 16:3-4, Paul writes concerning the gathered collection, “And when I arrive, I will send those whom you accredit by letter to carry your gift to Jerusalem. If it seems advisable that I should go also, they will accompany me.” In other words, Paul suggests that someone else, rather than himself, accompany the Corinthians’ contribution to Jerusalem — he will go only if it seems appropriate. It seems likely, therefore, that Paul was accompanied from Greece to Jerusalem by this large group to demonstrate that he had not absconded with any of the collection and to provide more security as he made the journey. Acts never mentions the collection at all, except in Paul’s cryptic allusion to bringing alms to his nation in his speech before Felix in Acts 24:17.

9. Paul’s Companions in Corinth

In Romans 16:21-23, Paul provides a list of his companions in Corinth: “Timothy, my fellow worker, greets you; so do Lucius and Jason and Sosipater, my kinsmen. I Tertius, who wrote this letter, greet you in the Lord. Gaius, who is host to me and to the whole church, greets you. Erastus, the city treasurer, and our brother Quartus, greet you.” Strikingly, Sopater and Timothy are two names also listed among Paul’s travelling companions in Acts 20:4. As discussed previously, Gaius of Derbe is probably a different individual from the Gaius mentioned in Romans, since the latter individual is said to be Paul’s host, implying he lived in Corinth or nearby Achaia. This is likely the same Gaius as the one baptized by Paul in 1 Corinthians 1:14, suggesting a strong Corinthian connection. Gaius was, in fact, one of the most common Roman praenomina (first names) in antiquity. This also supports the independence of Acts and Romans — if the author of Acts were using the epistle to the Romans as a source for the composition of his own narrative, it is peculiar that he listed an individual by the same name as the figure mentioned in Romans, even though these are separate individuals. A copyist would be more likely to link an individual bearing the name of Gaius to Corinth rather than Derbe.

Note that Sopater (Σώπατρος), which was a much less frequent name, is a shortened or contracted form of Sosipater (Σωσίπατρος), functioning much like a nickname. This slight difference in spelling between Acts and Romans again indicates that Luke is probably not using Romans as a source for the composition of his narrative (nor vice versa). Further supporting this is that the names only partially overlap between Acts and Romans. Moreover, of the remaining five names given in Acts, three are mentioned in Paul’s prison epistles, which were composed in Rome — namely, Trophimus (2 Tim 4:20), Aristarchus (Col 4:10, Philem 24), and Tychicus (Eph 6:21; Col 4:7; 2 Tim 4:12). Thus, these three individuals apparently ended up travelling with Paul as far as Rome.

10. As I Directed the Churches of Galatia

In 1 Corinthians 16:1, Paul writes, “Now concerning the collection for the saints: as I directed the churches of Galatia, so you also are to do.” According to Acts, the last churches visited by Paul prior to his coming to Ephesus were in Galatia and Phrygia (Acts 18:23). Thus, it makes sense that he left those instructions there. That visit was a couple of years prior to his writing 1 Corinthians. However, there is no indication that Paul had visited any other churches in the interim. Thus, Galatians remained the last place where he had delivered these instructions. This is further confirmed by a passing comment in Galatians 2:10 that Paul was eager to “remember the poor,” suggesting that he had in fact spoken on this subject in Galatia.

11. All the Way Around to Illyricum

In Romans 15:18-20, Paul writes, “For I will not venture to speak of anything except what Christ has accomplished through me to bring the Gentiles to obedience – by word and deed, by the power of signs and wonders, by the power of the Spirit of God – so that from Jerusalem and all the way around to Illyricum I have fulfilled the ministry of the gospel of Christ.” As shown on the map below, Illyricum was a province to the northwest of Macedonia.

Paul goes on to talk about how he hopes to visit Rome and ultimately travel to Spain, which was still further west than either Rome or Illyricum. Paul appears to be giving an eastern and northwestern reference point concerning the geographical sleep of his ministry up to this point, followed by his anticipation of travelling even further west, to Rome and Spain.

For reasons discussed previously, we can pinpoint the writing of Romans to Acts 20:3, when Paul spent three months in Corinth, in Greece. Just prior to this point, there would have been opportunity for Paul to have journeyed as far northwest as Illyricum. Indeed, this journey through Macedonia is described by Acts 20:2 in general terms: “When he had gone through these regions and had given them much encouragement, he came to Greece.” The Greek here, παρακαλέσας αὐτοὺς λόγῳ πολλῷ, literally means “having exhorted them with many words.” It is quite plausible, then, that Paul traveled around in Macedonia and reached as far as the northwestern border with Illyricum. However, in the earlier journey to Macedonia (recounted in Acts 16:9-17:14) , there would have been no such opportunity. Indeed, Paul’s journey is charted along the eastern border of Macedonia, with the cities precisely named as Philippi, Amphipolis, Apollonia, Thessalonica, and Berea. Paley summarizes, “It must have been…upon that second visit [to Macedonia], if at all, that he approached Illyricum; and this visit, we know, almost immediately preceded the writing of the epistle. It was natural that the apostle should refer to a journey which was fresh in his thoughts.”[xi]

This coincidence that the epistle to the Romans appears to have been written during Paul’s three month stint in Greece in Acts 20:3 with the fact that Acts 20:2 allows for travel as far northwest as Illyricum is unlikely to be the result of clever contrivance, particularly since we inferred when, within Acts, the epistle to the Romans was written on entirely independent grounds. Moreover, the province of Illyricum is never explicitly mentioned in Acts at all.

12. Divisions in Corinth

In 1 Corinthians 1:10-12, Paul addresses divisions within the Corinthian church:

I appeal to you, brothers, by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that all of you agree, and that there be no divisions among you, but that you be united in the same mind and the same judgment. 11 For it has been reported to me by Chloe’s people that there is quarreling among you, my brothers. 12 What I mean is that each one of you says, “I follow Paul,” or “I follow Apollos,” or “I follow Cephas,” or “I follow Christ.”

What was the cause of these factions among the Corinthians? A clue as to Paul’s meaning is provided by 1 Corinthians 1:17: “For Christ did not send me to baptize but to preach the gospel, and not with words of eloquent wisdom, lest the cross of Christ be emptied of its power.” Another clue is provided by 2 Corinthians 10:9-10, in which Paul writes, “I do not want to appear to be frightening you with my letters. For they say, ‘His letters are weighty and strong, but his bodily presence is weak, and his speech of no account.’” Apparently Paul, though a gifted writer, was not a great orator. In 2 Corinthians 11:5-6, moreover, Paul adds, “Indeed, I consider that I am not in the least inferior to these super-apostles. Even if I am unskilled in speaking, I am not so in knowledge; indeed, in every way we have made this plain to you in all things.” This suggests that the factions at Corinth may have been a result of the superiority of Apollos and Cephas as public speakers. This makes sense since Corinth, as a Greek city, was naturally impressed by flashy rhetoric and persuasive speeches. When we turn over to Acts 18:24-28, we discover that Apollos was, in fact, a gifted orator, consistent with those clues in 1 Corinthians:

Now a Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, came to Ephesus. He was an eloquent man, competent in the Scriptures. 25 He had been instructed in the way of the Lord. And being fervent in spirit, he spoke and taught accurately the things concerning Jesus, though he knew only the baptism of John. 26 He began to speak boldly in the synagogue, but when Priscilla and Aquila heard him, they took him aside and explained to him the way of God more accurately. 27 And when he wished to cross to Achaia, the brothers encouraged him and wrote to the disciples to welcome him. When he arrived, he greatly helped those who through grace had believed, 28 for he powerfully refuted the Jews in public, showing by the Scriptures that the Christ was Jesus (1 Corinthians 18:24-28).

The text indicates that Apollos was known at Corinth for his skills as a public speaker and debater. The casual consistency between 2 Corinthians and Acts supports the historicity of Acts.

13. Silas’ and Timothy’s Preaching in Corinth

According to Acts 18:1,5: “After this Paul left Athens and went to Corinth…When Silas and Timothy arrived from Macedonia, Paul was occupied with the word, testifying to the Jews that the Christ was Jesus.” Compare this with 2 Corinthians 1:19: “For the Son of God, Jesus Christ, whom we proclaimed among you, Silvanus and Timothy and I, was not Yes and No, but in him it is always Yes.” As discussed earlier, Paul wrote this epistle from Macedonia. The reference to Silvanus (i.e., Silas) and Timothy, therefore, matches the history. Though this coincidence is more direct than many of those discussed in this article, it must be remembered (as has previously been established) that Acts and 2 Corinthians are independent sources. Furthermore, Acts and 2 Corinthians use a different spelling for the name. 2 Corinthians calls him by the name Σιλουανός, whereas Acts uses the contracted name Σιλας. Paley remarks,

“The similitude of these two names, if they were the names of different persons, is greater than could easily have proceeded from accident; I mean that it is not probable, that two persons placed in situations so much alike should bear names so nearly resembling each other. On the other hand, the difference of the name in the two passages negatives the supposition of the passages, or the account contained in them, being transcribed either from the other.”[xii]

It may also be observed that Paul’s first epistle to the Thessalonians indicates that it was sent by Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy (1 Thess 1:1). This further confirms that they were the same person, since we know from Acts that Silas and Timothy were involved in Paul’s ministry in Thessalonica (Acts 17:1,10,15). This actually constitutes another undesigned coincidence, since Acts 17:1,10 only says explicitly that Paul & Silas were involved in Paul’s ministry in Thessalonica. It is only in Acts 17:14-15, when we are told that Silas & Timothy remained behind in Berea, that it is implied that presumably Timothy had been there the whole time, even though he went unmentioned in connection to Paul’s ministry in Thessalonica. 1 Thessalonians also further supports Acts’ connection with 2 Corinthians, as discussed above, since we have independent grounds for thinking that Paul wrote 1 Thessalonians from Corinth, at a time when Timothy had recently returned from Macedonia with a report on the spiritual wellbeing of the Thessalonian Christians (1 Thess 3:1-5), which correlates with the arrival of Silas and Timothy in Corinth from Macedonia in Acts 18:5.

14. Letters of Recommendation

In 2 Corinthians 3:1, Paul writes, “Are we beginning to commend ourselves again? Or do we need, as some do, letters of recommendation to you, or from you?” (emphasis added). Compare this to Acts 18:27: “And when he [Apollos] wished to cross to Achaia, the brothers encouraged him and wrote to the disciples to welcome him.” Recall that Corinth is the capital of Achaia. McGrew remarks,

“This comment dovetails with the statement in Acts that, when Apollos first went to Corinth, he was sent with letters of recommendation from the believers at Ephesus. It is possible that Paul does not have Apollos personally in mind when writing this in II Corinthians. In that case, the verse fits with Acts by alluding to letters of recommendation as a practice in the early church. But there is also plausibility to the suggestion that some in the Corinthian church were still comparing Paul with Apollos and that Paul, though not wishing to attack Apollos, nonetheless in his frustration alludes to the fact that he, unlike ‘some,’ does not need such letters to commend himself.”[xiii]

15. Paul and Apollos at Corinth

In 1 Corinthians 3:6, Paul writes, “I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth.” Paul’s wording implies that Apollos came and ministered at Corinth only after Paul’s departure from Achaia, but before the composition of 1 Corinthians. This comports with the timeline supplied in Acts (18:1,24-28; 19:1). As discussed previously, we have strong independent grounds for thinking that 1 Corinthians was written from Ephesus, in Acts 19:22, after Paul had sent Timothy and Erastus to Macedonia. Thus, Acts and 1 Corinthians correlate quite precisely. The two writings, however, refer to Apollos in entirely different contexts and for unrelated purposes. It is, therefore, very unlikely that one text was borrowing from the other. In Acts, Apollos is noted for knowing only John’s baptism and for his association with Aquila and Priscilla, while in the epistle he is mentioned only in connection with divisions at Corinth and then in the statement, “I planted, Apollos watered.” That second phrase unintentionally reflects the true chronological order of events recorded in Acts, but Paul introduces it solely to make a theological point that growth ultimately comes from God.

***Click Here for Part 2 in this series***

References:

[i] Scripture references are to the ESV unless otherwise noted.

[ii] William Paley, Horae Paulinae, or the Truth of the Scripture History of St. Paul Evinced (London: R. Faulder, 1791).

[iii] Paley 1791.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Lydia McGrew, Hidden In Plain View: Undesigned Coincidences in the Gospels and Acts (DeWard Publishing Company, 2017), 140.

Recommended Resources:

The New Testament: Too Embarrassing to Be False by Frank Turek (DVD, Mp3, and Mp4)

Why We Know the New Testament Writers Told the Truth by Frank Turek (DVD, Mp3 and Mp4)

Early Evidence for the Resurrection by Dr. Gary Habermas (DVD), (Mp3) and (Mp4)

The Footsteps of the Apostle Paul (mp4 Download), (DVD) by Dr. Frank Turek

Dr. Jonathan McLatchie is a Christian writer, international speaker, and debater. He holds a Bachelor’s degree (with Honors) in forensic biology, a Masters’s (M.Res) degree in evolutionary biology, a second Master’s degree in medical and molecular bioscience, and a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology. Currently, he is an assistant professor of biology at Sattler College in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. McLatchie is a contributor to various apologetics websites and is the founder of the Apologetics Academy (Apologetics-Academy.org), a ministry that seeks to equip and train Christians to persuasively defend the faith through regular online webinars, as well as assist Christians who are wrestling with doubts. Dr. McLatchie has participated in more than thirty moderated debates around the world with representatives of atheism, Islam, and other alternative worldview perspectives. He has spoken internationally in Europe, North America, and South Africa promoting an intelligent, reflective, and evidence-based Christian faith.

Originally posted at: https://bit.ly/3Yfxcac