This article is the first in a nine-part series that will explain the story of how we got our Bible. That is, the Bible did not fall from the sky into our hands. Rather, the Bible is the result of a long process that begins in the mind of God and ends with our modern English translations.

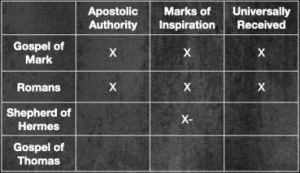

The process involves inspiring texts, collecting certain books, rejecting others, copying manuscripts, evaluating thousands of manuscripts to recreate the originals as closely as possible, translating the Hebrew and Greek texts into English, and creating readable translations in our modern local language.

As you might have guessed, this series will deal with some of the most crucial issues surrounding the Bible: topics such as the canon, the Apocrypha, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Pseudepigraphal Gospels, textual criticism, the King James Only movement, and much more. I hope you will join me on this journey through the fascinating history of the Bible. If you are not already subscribed, please click subscribe to receive updates on future posts.

That being said, let’s start with the inspiration.

Plenary and Verbal Inspiration

Paul writes: “All Scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness, so that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work” (2 Timothy 3:16-17, ESV). Here are some concepts worth highlighting.

First, the Greek word “theopneustos,” translated “inspired,” technically means “God-breathed, God-breathed, God-inspired,” so Paul is saying that God “breathes out” rather than “inspires” the text. In other words, He is the source behind all Scripture.

Second, notice that God inspires Scripture, not the authors themselves. This necessary distinction means that God’s inspiration extends to the final product of Scripture itself, not to the everyday life of the human author. That is, the authors were fallible while God-inspired Scripture was not.

Third, Paul points out that ALL Scripture is inspired, not just parts of it. Some have wrongly taught that inspiration only covers the parts that deal with faith and morals. But that is not what Paul is writing about. When he says “all,” he includes the Canaanite conquests, the talking donkey, and the Levitical code.

The biblical authors affirm inspiration

Several times throughout the Old Testament, the authors acknowledged that they were writing the words of God. Consider these examples:

“ Then the Lord said to Moses, ‘Write this in a scroll for a memorial, and tell Joshua that I will completely blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven ’” (Exodus 17:14).

“ Then the Lord put forth his hand and touched my mouth. And the Lord said to me, ‘Behold, I have put my words in your mouth ’” (Jeremiah 1:9).

“ The word of the Lord that came to Hosea son of Beeri in the days of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah, and in the days of Jeroboam son of Joash king of Israel ” (Hosea 1:1).

“ On the fifth day of the month, in the fifth year of King Jehoiakim’s exile, the word of the Lord came to Ezekiel the priest, son of Buzi, in the land of the Chaldeans by the River Chebar; and there the hand of the Lord came upon him ” (Ezekiel 1:2-3).

Furthermore, the New Testament authors affirm the inspiration of the Old Testament:

“ All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet: ” (Matthew 1:22).

“ Brothers, the Scripture had to be fulfilled, which the Holy Spirit foretold through the mouth of David concerning Judas, who became a guide for those who arrested Jesus ” (Acts 1:16).

“ David himself said through the Holy Spirit: ‘The Lord said to my Lord: “Sit at my right hand until I put your enemies under your feet ”” (Mark 12:36).

This last verse was quoted by Jesus Himself. That is, Jesus affirmed the inspiration of the Old Testament.

What about the New Testament?

When Paul writes that “all Scripture is given by inspiration of God,” he was most likely referring to the Old Testament, since the word Scripture (“graphe”) refers to the Old Testament when used in the New. We must also remember that when Paul wrote this letter, parts of the New Testament had not yet been written. Was inspiration then limited to the Old Testament? No, it was not.

Notice how Peter speaks of Paul’s letters in 2 Peter 3:15-16: “And consider the patience of our Lord as salvation, just as our beloved brother Paul also wrote to you, according to the wisdom given to him. And in all his letters he speaks about this matter. In them there are some things that are hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable distort— just as they distort the rest of the Scriptures —to their own destruction.” Peter seems to equate Paul’s letters with the Old Testament and grant them equal authority.

1 Timothy 5:18 is another crucial text on this issue. Paul writes, “ For the Scripture says, ‘ You shall not muzzle an ox while it treads out the grain,’ and, ‘The laborer is worthy of his wages.’” Paul quotes two different passages in this verse and refers to both as Scripture. The first is found in Deuteronomy 25:4 and the second in Luke 10:7. This means that Paul thought that Luke’s Gospel was Scripture just as the Old Testament is.

We even have some clues that suggest the apostles knew they were writing God’s Word. Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 14:37, “If anyone thinks he is a prophet or spiritual, let him acknowledge that what I am writing to you is a command from the Lord .” Additionally, Paul states in 1 Thessalonians 2:13, “For this reason we also thank God continually that when you received the word of God which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men but as it really is, the word of God, which also works in you who believe.”

Peter also comments, “that you may remember the words spoken beforehand by the holy prophets and the commandment of the Lord and Savior as declared by your apostles ” (2 Peter 3:2). The apostles, then, believed that they spoke with authority from God. And they could do so because Jesus promised them that the Holy Spirit would guide them in the process. (John 14:26; 16:13)

Mechanical dictation?

Peter points out, “But know this first of all, that no prophecy of Scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation. For no prophecy was ever made by the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit” (2 Peter 1:20-21). Some suggest that the activity of the Holy Spirit is a lot like annoying mechanical dictation. But this would be a mistake. As I mentioned earlier, inspiration extends only to the finished product of Scripture. That is, God worked in and through the abilities, personalities, and experiences of the human authors as they wrote their various works. In short, the biblical authors produced their Scriptures in different ways.

The author of Hebrews touches on this point when he tells us, “God spoke long ago, at sundry times, and in divers manners, to the fathers by the prophets” (Hebrews 1:1). Notice how he states that the prophets spoke “in many ways.” And Scripture makes abundantly clear these different ways. Consider a few examples:

- Research/Interpretation: “ Now concerning this salvation the prophets who prophesied of the grace to come to you searched and investigated diligently, seeking to know what person or time the Spirit of Christ within them was indicating when he foretold the sufferings of Christ and the glories that would follow ” (1 Peter 1:10-11)

- Dictation: “ Write to the angel of the church in Ephesus… ” (Revelation 2:1)

- Investigative Search: “ Forasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a record of the things which are most certain among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word, it seemed fitting for me also, having diligently investigated everything from the beginning, to write an orderly account to you, most excellent Theophilus ” (Luke 1:1-3)

Furthermore, the biblical authors wrote poetry, wisdom literature, letters, and prophecies. And in doing so, God worked through them in such a way that did not override their unique perspective. At the same time, He oversaw the process to ensure that their message was accurate when communicated. As the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy notes: “We affirm that God, in His work of inspiration, utilized the distinctive personalities and literary styles of the writers He had chosen and prepared. We deny that God, by having these writers use the very words He chose, overrode their personalities.”

Evidence of Inspiration

Some argue that inspiration appeals to circular reasoning because we must appeal to Scripture itself to claim inspiration. While that is a fair criticism, Christians are right to appeal to Scripture because it is our highest authority. If we appeal, for example, to human reasoning, then we elevate human reasoning to a higher authority than Scripture.

That said, we do have good evidence for inspiration in fulfilled prophecies. I could list dozens of fulfilled prophecies, but I will only briefly touch on two of them. First, Isaiah 53 correctly predicts Christ’s crucifixion. Of note is the fact that Isaiah says, “He was pierced for our transgressions” (Isaiah 53:5, ESV). This method of death is significant because in Isaiah’s day, the Jewish methods of execution were stoning or hanging. How could Isaiah correctly predict the kind of death Jesus would suffer seven hundred years earlier?

Another example is Daniel 9. Although I won’t go into details, Daniel predicts the exact time of Christ’s arrival. Furthermore, Daniel says that the Messiah will be “slain” (killed) just before the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple. Jesus was crucified in A.D. 30. The Romans destroyed Jerusalem and the temple in A.D. 70.

Inerrancy

Inerrancy follows naturally from inspiration. In other words, if God is the author behind the entire Bible, then everything must be true because God always tells the truth. Consider the following texts:

“ in which it is impossible for God to lie ” (Hebrews 6:18)

“ Now therefore, O Lord God, you are God, your words are truth ” (2 Samuel 7:28)

“ Every word of God is proven; ” (Proverbs 30:5)

“ Sanctify them by the truth; your word is truth” (John 17:17)

Notice that Jesus doesn’t just say that God’s word is true, but that it is the TRUTH. It is the absolute standard of truth. And lest anyone think that this idea of inerrancy is a modern invention, listen to some of the church fathers:

“You have searched the Scriptures, which are true and have been given by the Holy Spirit. You know that nothing unjust or false is written in them,” Clement of Rome, 1st century.

“The statements of Holy Scripture never contradict the truth,” Tertullian, 3rd century.

“Some are of the opinion that the Scriptures do not agree or that the God who gave them is false. But there is no disagreement at all. Far from it! The Father, who is the truth, cannot lie.” Athanasius, 4th century.

In short, while Scripture does not give us exhaustive knowledge of all things (how to change a tire, for example), it does not assert anything that is contrary to fact.

The next post

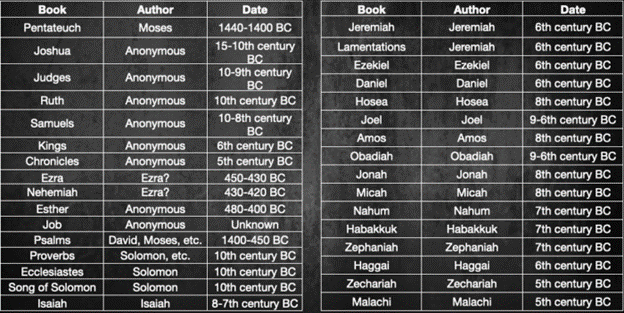

In the next post we will look at how the Old Testament came into being. In particular, we will address the nature of the development of the Old Testament, its authors and editors, as well as its preservation.

Recommended resources in Spanish:

Stealing from God ( Paperback ), ( Teacher Study Guide ), and ( Student Study Guide ) by Dr. Frank Turek

Why I Don’t Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist ( Complete DVD Series ), ( Teacher’s Workbook ), and ( Student’s Handbook ) by Dr. Frank Turek

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Ryan Leasure holds a Master of Arts degree from Furman University and a Master of Divinity degree from the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He is currently a Doctor of Ministry candidate at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He also serves as pastor at Grace Bible Church in Moore, SC.

Original blog source: https://bit.ly/3w9hBum Translated by Monica Pirateque Edited by Daniela Checa Delgado