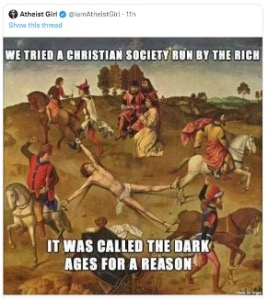

We have all heard about the “Dark Ages” between 500 AD and 1500 AD. Some common descriptions include:

- “There was a time when religion ruled the world. It is known as the Dark Ages.”[1] – Ruth Hurmence Green (1915-1981, a notable atheist with the publication of her book The Born Again Skeptic’s Guide to the Bible).

- Joseph Lewis in An Atheist Manifesto claims that “If you do not want to stop the wheels of progress; if you do not want to go back to the Dark Ages; if you do not want to live again under tyranny, then you must guard your liberty, and you must not let the church get control of your government. If you do, you will lose the greatest legacy ever bequeathed to the human race—intellectual freedom.”

- Jeffrey Taylor, a correspondent for Atlantic Monthly and NPR’s All Things Considered states on com, “There is a reason the Middle Ages in Europe were long referred to as the Dark Ages; the millennium of theocratic rule that ended only with the Renaissance (that is, with Europe’s turn away from God toward humankind) was a violent time.”

- Even as recently as Catherine Nixey’s book The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World states emphatically that “This is a book about the Christian destruction of the classical world. The Christian assault was not the only one – fire, flood, invasion, and time itself all played their part – but this book focuses on Christianity’s assault in particular” (xxxv). (See below for several extensive reviews and critiques of Nixey’s book.)

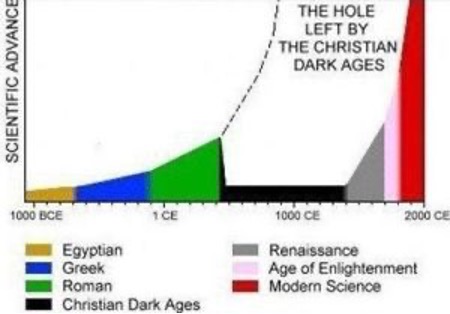

- The diagram below, which has circulated on the internet, claims to demonstrate that the Middle Ages caused a tremendous hole in learning and advancement caused by Christianity.

- Anne Fremantle in her study of medieval philosophers, The Age of Belief (1954), wrote: “of a dark, dismal patch, a sort of dull and dirty chunk of some ten centuries.”

- Voltaire, the French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher, who attacked the church, described the period as one when “barbarism, superstition, and ignorance covered the face of the world.”

- Rousseau declared that the era following the fall of Rome caused “Europe [to] relapse into the barbarism of the earliest ages. The people of this part of the world . . . lived some centuries ago in a condition worse than ignorance.”

- The great Roman historian Edward Gibbon called the fall of Rome the “triumph of barbarism and religion.” The famed scientist Carl Sagan also attributes a millennium gap [during the Middle Ages as] a poignant lost opportunity for the human species.”

Some other memes likewise blame Christianity for the so-called “Dark Ages” stunted growth.

Unfortunately, this derision of the Middle Ages as a “darkened period” continues into contemporary descriptions. Such perpetrators include Bertrand Russell, Charles Van Doren, and William Manchester.

One Among Many Myths About Christianity

Like the myth that the church hindered science, or that everyone in the middle ages believed the earth was flat, or that Galileo was thrown in jail for promoting the heliocentric model of the universe (which you can read about in my previous posts linked); the term “dark ages” is a pejorative term to deride the period as backwards, ignorant, and dismal. Given that the Christian church was the most influential institution in the Middle Ages, to reference that period as the “Dark Ages” is, in essence, to slander Christianity. Who, in their right mind, wants to associate themselves with “incessant warfare, corruption, lawlessness, obsession with strange myths, and an almost impenetrable mindlessness” as Manchester does in his A World Lit Only by Fire.

The Problem with This Myth

The problem with this myth is that it is so contrary to the facts. If the “dark ages” were so unproductive and backward, how does one explain the proliferation of inventions and developments during this time period? A simple listing of inventions, discoveries and developments demonstrates that the Middle Ages were anything but dark:

- The collar and harness for horses and oxen enabled them to draw very heavy wagons, with increases in speed

- The 8th century invention of iron horseshoes protecting the feet of horses by greatly improving their traction in difficult conditions

- The swivel axel (9th century) was made large transport carts much more maneuverable

- The invention of the horse-drawn furrow plow increased food production

- The watermill was invented in the Middle Ages

- The mechanical manufacturing of paper instead of being done by hand and foot

- Wind power was harnessed to mill, grind, and pump water

- Eyeglasses were invented in 1284 in northern Italy

- The mechanical clock, a 13th-century invention, for centuries existed only in Medieval Europe

- The blast furnace (12th century)

- Spinning wheel (13th century)

- The agricultural revolution of the three-field system

- Chimneys (12th century)

- Universities (1088 AD) [2]

- Quarantine (14th century)

- Musical Notation (11th century)

- Western Harmony

- Local Self-Government

- Chartered Towns

Also, perpetuated about the “dark ages” is the loss of literary concern. Stephen Greenblatt in The New Yorker (promoting his book The Swerve) declares that:

It is possible for a whole culture to turn away from reading and writing. As the empire crumbled and Christianity became ascendant, as cities decayed, trade declined, and an anxious populace scanned the horizon for barbarian armies, the ancient system of education fell apart. What began as downsizing went on to wholesale abandonment. Schools closed, libraries and academies shut their doors, professional grammarians and teachers of rhetoric found themselves out of work, scribes were no longer given manuscripts to copy. There were more important things to worry about than the fate of books.

In truth, the Middle Ages “did have a thriving literary and intellectual culture in which monks played a crucial, creative, and engaged role.” (source). Here is a small list of literary, historical, and philosophical masterpieces written during the so-called “Dark Ages”:

- Alexiad, Anna Comnena

- Beowulf

- Caedmon’s Hymn

- Book of the Civilized Man, Daniel of Beccles

- The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer

- Consolation of Philosophy, Boethius

- Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio

- The Dialogue, Catherine of Siena

- La divina commedia (The Divine Comedy), Dante Alighieri

- First Grammatical Treatise, 12th-century work on Old Norse phonology

- Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People), the Venerable Bede

- The Lais of Marie de France, Marie de France

- Mabinogion, various Welsh authors

- Il milione (The Travels of Marco Polo), Marco Polo

- Le Morte d’Arthur, Sir Thomas Malory

- Poem of the Cid, anonymous Spanish author

- Proslogium, Anselm of Canterbury

- Queste del Saint Graal (The Quest of the Holy Grail), anonymous French author

- Revelations of Divine Love, Julian of Norwich

- Sic et Non, Abelard

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, anonymous English author

- The Song of Roland, anonymous French author

- Spiritual Exercises, Gertrude the Great

- Summa Theologiae, Thomas Aquinas

- The Tale of Igor’s Campaign, anonymous Russian author

- Tirant lo Blanc, Joanot Martorell

- The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, John Mandeville

- Troilus and Criseyde, Geoffrey Chaucer

- Yvain: The Knight of the Lion, Chrétien de Troyes

A host of others can be mentioned but just check out this wikipedia article on “Medieval Literature.”

Ad Hominem

The fact of the matter is the term “dark ages” is a form of the ad hominem argument. In short, it’s name-calling. Until one can demonstrate that the middle ages was backward and made no technological, societal, or intellectual advancement (which is not possible given the prolific advancement during this time as shown above), the term “Dark Ages” is just a term of derision, void of any substance.

One more telling point to demonstrate that the Middle Ages were much more advanced than even our current modern and contemporary age. In the Middle Ages, a peculiar institution fell into disfavor but tragically was revived in the modern era: slavery. This very fact shows that the Modern Age is [arguably] much darker than the Middle Ages ever were. While slavery never disappeared, it was nothing like the transatlantic slave trade or modern slavery.

As Anthony Esolen, professor of English at Providence College says at the end of the video below:

“Instead of the ‘Dark Ages’ as it is popularly called. The Middles Ages might better be described as the “Brilliant Ages.’”

Additional Resources on the Middle Ages

Quick Quotes from the Experts:

- “Nevertheless, serious historians have known for decades that these claims [that the Middle Ages were dark] are a complete fraud. Even the respectable encyclopedias and dictionaries now define the Dark Ages as a myth. The Columbia Encyclopedia rejects the term, nothing that ‘medieval civilization is no longer thought to have been so dim.’ Britannica disdains the name Dark Ages as ‘pejorative.’ And Wikipedia defines the Dark Ages as a ‘supposed period of intellectual darkness after the Fall of Rome.’ These views are easily verified.” (Rodney Stark, How the West Won. ISI Books, 2014)

- “Let’s set the record straight. From 962 to 1321, Europe enjoyed one of the most magnificent flourishings of culture the world has ever seen. In some ways, it was the most magnificent. And this was not despite the fact that the daily tolling of the church bells provided the rhythm of men’s lives, but because of it.” (Anthony Esolen, The Politically Incorrect Guide to Western Civilization, p.132)

- “It’s not hard to kick this nonsense to pieces, especially since the people presenting it know next to nothing about history and have simply picked up these strange ideas from websites and popular books. The assertions collapse as soon as you hit them with hard evidence. I love to totally stump these propagators by asking them to present me with the name of one – just one – scientist burned, persecuted, or oppressed for their science in the Middle Ages. They always fail to come up with any.” (Tim O’Neill “The Dark Age Myth: An Atheist Reviews ‘God’s Philosophers’” Strange Notions)

- “Western civilization was created in medieval Europe. The forms of thought and action which we take for granted in modern Europe and America, which we have exported to other substantial portions of the globe, and from which indeed we cannot escape, were implanted in the mentalities of our ancestors in the struggles of the medieval centuries.” (Cambridge University historian George Holmes’ Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe)

Books:

- The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe by Matthew Gabriele and David M. Perry (Harper, 2021)

- The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Science by Seb Falk (WW Norton, 2020)

- The Politically Incorrect Guide to Western Civilization by Anthony Esolen (Regnery, 2008)

- The Genesis of Science: How the Christian Middle Ages Launched the Scientific Revolution, by James Hannam. (Regnery, 2011)

- Those Terrible Middle Ages: Debunking the Myths, by Regine Pernoud. (Ignatius, 2000)

- How the West Won: The Neglected Story of the Triumph of Modernity by Rodney Stark (ISI Books, 2014)

- Cathedral, Forge and Waterwheel: Technology and Invention in the Middle Ages by Joseph and Frances Gies(Harper, 1994)

Articles:

- “The Great Myths 15: What About ‘The Dark Ages?’” by Tim O’Neill. History for Atheists.Sept 29, 2024.

- “The ‘Dark Ages’ Were a lot Brighter Than We Give Them Credit For” by Richard Swan. The Independent. October 17, 2012

- “The Dark Age Myth: An Atheist Reviews ‘God’s Philosophers’” by Tim O’Neill. Strange Notions d.

- “5 Ridiculous Myths You Probably Believe about the Dark Ages” by J. Wisniewski. Cracked. September 27, 2013

- “Top 10 Reasons the Dark Ages Were Not Dark” by Jamie Frater. Listverse June 9, 2008

- “15 Myths About the Middle Ages” by Sandra Alvarez and Peter Konieczny. Medievalists June 27, 2014

- “Misconceptions About the Middle Ages Debunked Through Art History” by Bryan Keene and Rheagan Martin. Iris: The Online Magazine of the Getty February 20, 2015

- “Myths about the ‘Dark Ages’” by John Tertullian. Contra Celsum April 13, 2011

- “How the Middle Ages Really Were” by Tim O’Neill. Huffington Post September 8, 2014

- “Top 10 Inventions of the Middle Ages” by Jamie Frater. Listverse September 22, 2007

- “Review of The Darkening Ageby Catherine Nixey” by Tim O’Neill. History for Atheists November 29, 2017

- “6 Reasons the Dark Ages Weren’t So Dark” by Sarah Pruitt. comMay 31, 2016

- “Christianity and the So-Called ‘Dark Ages’” by Melissa Cain Travis. The Worldview Bulletin Newsletter. Mar 8, 2024.

Videos:

- Anthony Esolen, “How Dark Were the Dark Ages?” PragerU (26 Jan 2015) at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cqzq01i2O3U&embeds_referring_euri=https%3A%2F%2Fischristianitytrue.wordpress.com%2F&source_ve_path=OTY3MTQ

- Michael Keys, “The Myth of a Christian Dark Ages,” Discovery Institute & ISI Books (2019) at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cqzq01i2O3U&embeds_referring_euri=https%3A%2F%2Fischristianitytrue.wordpress.com%2F&source_ve_path=OTY3MTQ

- “Dark Ages? Bad Faith #1” God: New Evidence (2017) at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WJBR1_Ua1yA

Book Reviews:

- The Swerve: How The World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt

Greenblatt’s Pulitzer Prize winning (and National Book Award, MLA book award, amongst others) The Swerve (2011) tells “a literary detective story about an intrepid Florentine bibliophile named Poggio Braccionlini, who, in 1417, stumbled upon a 500-year-old copy of [Lucretian’s] De Rerum Natura [On the Nature of Things] in a German monastery and set the poem free from centuries of neglect to work its intellectual magic on the world.” (source) While the literary side of the story is commendable (Greenblatt is a Shakespearean expert), it is the historical matter that is problematic. Greenblatt’s view of the Middle Ages continues to it as a dark and shallow intellectual vacuum in which the Renaissance (and later the Enlightenment) overcame its backward and regressive mentality. Greenblatt declares in his The New Yorker article “The Answer Man: An Ancient Poem was Discovered – and the World Swerved”:

“Theology provided an explanation for the chaos of the Dark Ages: human beings were by nature corrupt. Inheritors of the sin of Adam and Eve, they richly deserved every miserable catastrophe that befell them. God cared about human beings, just as a father cared about his wayward children, and the sign of that care was anger. It was only through pain and punishment that a small number could find the narrow gate to salvation. A hatred of pleasure-seeking, a vision of God’s providential rage, and an obsession with the afterlife: these were death knells of everything Lucretius represented.”

Unfortunately, Greenblatt hasn’t kept up with modern medieval historiography. Both Jim Hinch, in the Los Angeles Review of Books, and Laura Miles, over at Vox, point at his errors.

- “Why Stephen Greenblatt Is Wrong — and Why It Matters” by Jim Hinch | Los Angeles Review of BooksDec 1, 2012

Apparently, Lucretian was not as obscure in the Middle Ages as Greenblatt represents. Hinch writes that “Cambridge classicist Michael Reeve pointed out five years ago in The Cambridge Companion to Lucretius, scholars have long detected ‘Lucretian influence in north-Italian writers of the ninth to eleventh century, in the Paduan pre-humanists about 1300, in Dante, and in Petrarch and Bocaccio.’ Greenblatt cites the Cambridge Companion numerous times in his endnotes. Did he read it?” Obviously not.

Greenblatt’s caricature of the (read the quotes with sarcasm) “Dark Ages” as living life as if God is a cosmic kill joy is puzzling to Hinch as well: “Equally untrue is Greenblatt’s claim that medieval culture was characterized by ‘a hatred of pleasure-seeking, a vision of God’s providential rage and an obsession with the afterlife.’ I know Greenblatt has read Chaucer. He’s quoted from him in numerous books. Has he forgotten the ribald pleasure-seeking in The Canterbury Tales? What about the 13th-century French courtly love epic The Romance of the Rose? The twelfth-century Arthurian romances of Chrétien de Troyes? I find no rage in Dante’s complex vision of human morality and providential grace in the Divine Comedy. Nor do I detect an ounce of asceticism in the ravishing unicorn tapestries in the Cloisters Museum in New York. Or in the rose window in Chartres. Or in the Sainte Chapelle in Paris. Or in the gracious courts of the Alhambra.”

It seems Greenblatt is a good literary scholar, but a terrible Medieval historian, according to Hinch.

- “Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve racked up prizes — and completely misled you about the Middle Ages” by Laura Saetveit Miles | VoxJuly 20, 2016

Laura Saetveit Miles, professor at the University of Bergen in Norway, declares that

The Swerve doesn’t promote the humanities to a broader public so much as it deviously precipitates the decline of the humanities, by dumbing down the complexities of history and religion in a way that sets a deeply unfortunate precedent. If Greenblatt’s story resonates with its many readers, it is surely because it echoes stubborn, made-for-TV representations of medieval “barbarity” that have no business in a nonfiction book, much less one by a Harvard professor.

In a very revealing moment in Miles article on The Swerve she declares the book as dangerous:

“When I finished, I put down The Swerve on the table, and the academic side of my brain kicked back in. I had let myself read it as fiction. Yet it was supposed to be not fiction. When I thought of it as a scholarly book, and thought of all those thousands and thousands of people out there who read it and believed every word because the author is an authority and wins prizes, I realized: This book is dangerous.” [emphasis added]

Why is it dangerous? Because it is worse the Dan Brown’s The DaVinci Code:

“Every page of The Swerve strives to present the Renaissance as an intellectual awakening that triumphs over the oppressive abyss of the Dark Ages. The book pushes the Renaissance as a rebirth of the classical brilliance nearly lost during centuries mired in dullness and pain. (In Greenblatt’s Middle Ages, bored monks literally sit in the dark when not flagellating themselves.)

This invention of modernity relies on a narrative of good guys (Poggio, as well as Lucretius) defeating bad guys and thus bringing forth a glorious transformation. This is dangerous not only because it is inaccurate but, more importantly, because it subscribes to a progressivist model of history that insists on the onward march of society, a model that all too easily excuses the crimes and injustices of modernity.

But history does not fit such cookie-cutter narratives. Having studied medieval culture for nearly two decades, I can instantly recognize the oppressive, dark, ignorant Middle Ages that Greenblatt depicts for 262 pages as, simply, fiction. It’s fiction worse than Dan Brown, because it masquerades as fact.”

- “Book Review: The Swerve: How the Renaissance Began” byJohn Monfasani | Reviews in History July 2012

John Monfasani, professor of history at the University at Albany, State University of New York damning declares that “Greenblatt has penned an entertaining but wrong-headed belletristic tale.”

- A World Lit Only by Fire: the Medieval Mind and the Renaissance by William Manchester

Manchester begins his scathing history of the middle ages by claiming that

“The densest medieval centuries – the six hundred years between, roughly, A.D. 400 and A.D. 1000 – are still widely known as the Dark Ages.” (Manchester, 3) William Manchester does admit that modern historians have abandoned that phrase but the “intellectual life had vanished from Europe” and declares in the very first paragraph of the book: “Nevertheless, if value judgments are made, it is undeniable that most of what is known about the period is unlovely. After the extant fragments have been fitted together, the portrait which emerges is a melange of incessant warfare, corruption, lawlessness, obsession with strange myths, and an almost impenetrable mindlessness.”

The wikipedia entry about the book states that,

“In the book, Manchester scathingly posits, as the title suggests, that the Middle Ages were ten centuries of technological stagnation, short-sightedness, bloodshed, feudalism, and an oppressive Church wedged between the golden ages of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance.”

Technological stagnation

Short-sightedness

Bloodshed

An oppressive church

Between the golden age of Rome and the Renaissance.

Nothing really new about this negative report about the so-called “dark ages.” The only problem is that other modern historians have dismissed and criticized the book because of its gross errors, misinformation, and out of date understanding of the era.

Jeremy DuQuesnay Adams, professor and Altshuler Distinguished Teaching Professor of Medieval Europe of SMU and Ph.D. from Harvard (Manchester has an BA and MA in English, no training in history or a history degree), grudgingly reviewed the book. In Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies, Adams remarked that Manchester’s work contained “some of the most gratuitous errors of fact and eccentricities of judgment this reviewer has read (or heard) in quite some time.” He begins the review by lamenting:

“This is an infuriating book. The present reviewer hoped that it would simply fade away, as its intellectual qualities (too strong a word) deserved. Unfortunately, it has not: one keeps meeting well-intentioned, perfectly intelligent people (including some colleagues in other disciplines – especially the sciences) who have just read this book and want to discuss why anyone would ever become a medievalist.”

Adams goes on to point out that Manchester’s assertions about clothing, diet, and medieval person’s views of time and sense of self ran counter to the conclusions of established historians of the Middle Ages of the 20th-century.

An example of his errors is with the famed Pied Piper. Manchester claims that the Piper of Hamelin was “was horrible, a psychopath and pederast who, on June 24, 1484, spirited away 130 children in the Saxon village of Hammel and used them in unspeakable ways. Accounts of the aftermath vary. According to some, the victims were never seen again; others told of disembodied little bodies found scattered in the forest underbrush or festooning the branches of trees.”

Over at The Straight Dope we learn that “Manchester doesn’t footnote this passage” and that their own “research suggests that Manchester got some of the details wrong–among other things, he appears to be off about 200 years on the date.”

- “Review of A World Lit Only by Fire” Kirkus Review, May 20th, 2010.

This review reveals that Manchester, by his own admission, did NOT master any scholarship on the early 16th century, which ” dooms him to retelling the same old stories recounted countless times before.”

In the book’s “Author’s Note”, Manchester says, “It is, after all, a slight work, with no scholarly pretensions. All the sources are secondary, and few are new; I have not mastered recent scholarship on the early sixteenth century.

So, Manchester, who has no formal training in history, not a medievalist, admits to not using primary sources as well as not mastering any recent scholarship of the early 16th century, has penned a propaganda piece (at best) of the middle ages. Again, another myth that the middle ages were dark.

- The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World by Catherine Nixey

The Darkening Age by Catherine Nixey is one of the latest publications (2017) propagating the dark ages myth. Nixey studied classics at Cambridge and taught the subject for several years before becoming a journalist on the arts desk at the Times (UK). Her book, The Darkening Age, no surprise, focuses on “the Christian destruction of the classical world” (xxxv). Her prologue characterizes Christians as “destroyers, . . . marauding bands of bearded, black-robed zealots” whose “ . . . attacks were primitive, thuggish, and very effective.” She goes on to say that “these men moved in packs—later in swarms of as many as five hundred—and when they descended utter destruction followed” (xix).

Some of the reviews and reactions to Nixey’s book can be listed:

- The esteemed historian of Late Antiquity of Oxford University, Dame Averil Cameron, calls Nixey’s book “a travesty” condemning it as “overstated and unbalanced.”

- Lecturer of Medieval history at Exeter University, Dr. Levi Roach, stated that Nixey’s book “does not seek to present a balanced picture (…) this is a book of generalizations. (…) Nixey (…) is unwilling to see shades of grey” in his evaluation at Literary Review titled “At Cross Purposes.” He goes on to state in the article that, “to characterize late-antique Christians as ‘thugs’, as Nixey repeatedly does, it perhaps defensible, to call them ‘primitive’ and ‘stupid’, as she also does, is not. All to often Christians are cast as the aggressors, even when, as Nixey acknowledges more than once, they are responding to prior attacks.” And “Perhaps most worryingly, in embracing this line of argument [i.e., over-generalizing] Nixey ends up endorsing the long-debunked view of the Middle Ages as a period of blind faith and intellectual stagnation (which she again, problematically equates with one another.)”

- Tim O’Neill, over at his website History for Atheists, give a long, detailed analysis of Nixey’s book and concludes, “Good history books, including good popular history, should give the reader a greater insight into the period and the subject. They should make the reader better informed and, in doing so, make them wiser. They should deepen understanding, so that anything else read on the subject from that point tends to add layers to that depth. Watts’ book [The Final PaganGeneration] does this. O’Donnell’s book [Pagans: The End of Traditional Religion and the Rise of Christianity] does this. Duffy’s book [The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400-1580] does this. Nixey’s book does not. Anyone reading Nixey’s book is likely to come away thinking they know and understand more but will actually have learned things that would have to be unlearned or corrected later. Nixey’s is not a good history book. It is, as Dame Averil said so pithily, ‘a travesty’.”

- “Review of The Darkening Ageby Catherine Nixey” by Tim O’Neill. History for Atheists November 29, 2017

- “When History Turns Anti-Christian” by Bryan Litfin. The Gospel CoalitionApril 5, 2019

- “Book review, ‘The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World’ by Catherine Nixey” by Joshua Herring. The Acton Institute December 22, 2017

- “Blame the Christians” by Averil Cameron. The Tablet September 21, 2017

- “At Cross Purposes” by Levi Roach. Literary Review November 2017

- “Reactions to and Reviews of Catherine Nixey’s The Darkening Age” by Cornelis Hoogerwerf. What is Written October 22, 2017

References:

[1] [Editor’s Note: These quotes are presented as is. If any source information is lacking, that’s how it was presented in the original.]

[2] [Editor’s note: The University of Bologna, established in 1088, is widely considered the first and longest-running university in the world. The University of Al-Quaraouiyine in Fez, Morocco, a Muslim institution, is sometimes credited as the first but it’s disputed whether that school was a “university” (marked by free inquiry, freedom of thought, and free speech) before Bologna was established. Nevertheless, it too is a medieval creation. So Steve Lee’s thesis is unchallenged either way.

Recommended Resources:

How Philosophy Can Help Your Theology by Richard Howe (DVD Set, Mp3, and Mp4)

Debate: Does God Exist? Turek vs. Hitchens (DVD), (mp4 Download) (MP3)

Your Most Important Thinking Skill by Dr. Frank Turek DVD, (mp4) download

Stealing From God by Dr. Frank Turek (Book, 10-Part DVD Set, STUDENT Study Guide, TEACHER Study Guide)

J. Steve Lee has taught Apologetics for over two and a half decades at Prestonwood Christian Academy. He also has taught World Religions and Philosophy at Mountain View College in Dallas and Collin College in Plano. With a degree in history and education from the University of North Texas, Steve continued his formal studies at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary with a M.A. in philosophy of religion and has pursued doctoral studies at the University of Texas at Dallas and is finishing his dissertation at South African Theological Seminary. He has published several articles for the Apologetics Study Bible for Students as well as articles and book reviews in various periodicals including Philosophia Christi, Hope’s Reason: A Journal of Apologetics, and the Areopagus Journal. Having an abiding love for fantasy fiction, Steve has contributed chapters to two books on literary criticism of Harry Potter: Harry Potter for Nerds and Teaching with Harry Potter. He even appeared as a guest on the podcast MuggleNet Academia (“Lesson 23: There and Back Again-Chiasmus, Alchemy, and Ring Composition in Harry Potter”). He is married to his lovely wife, Angela, and has two grown boys, Ethan and Josh.

Originally posted at: https://bit.ly/3Gsq4BN