By Brian Chilton

One of the more difficult of the apologetics arguments to understand is that known as the ontological argument. The ontological argument finds root in Anselm of Canterbury’s famed declaration, “God is that, than which noting greater can be conceived.”[1] This is the say, God is the greatest of all possible beings. God, properly understood, is maximally great. Nothing could be greater than God. Thus, Anselm argues that if it is possible to conceive of the greatest possible beings, then that greatest possible being must exist. There is much to unpack in this argument. However, I would like to focus on arguments that provide reasons to believe that God is a necessary being.

Before we look at some arguments for the necessity of God’s existence, we must first define a necessary being. A necessary being is a being whose existence is mandatory due to a result of that being’s existence (i.e., contingency). For example, I exist only because of the necessity of my parents’ existence. My existence is contingent (based upon) the necessity of their existence. My parents’ existence is contingent (based upon) the necessity of their parents’ existence (my grandparents). The logical line of necessity continues until one finds the necessity of a maximally great being—a being that is transcendent, omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, and omnibenevolent. We know that maximally great being as God. Let’s look at three or four modern ontological arguments that make the case for the necessity of God’s existence.

- Necessity of God Found in Logical Necessity.

As we already unpacked the argument from necessity, we have found that God’s existence is mandatory. However, the logical necessity of God’s existence is found in the following argument presented by Douglas Grootius:

-

God is defined as a maximally great or Perfect Being.

-

The existence of a Perfect Being is either impossible or necessary (since it cannot be contingent).

-

The concept of a Perfect Being is not impossible, since it is neither non-sensical nor self-contradictory.

-

Therefore (a) a Perfect Being is necessary.

-

Therefore (b) a Perfect Being exists.[2]

The first premise notes that God is defined as a maximally great being, or Perfect Being. Premises 2 and 3 demonstrate the logical necessity that a Perfect Being is either an impossibility or a necessity. Since the existence of a Perfect Being is neither impossible, nonsensical, nor self-contradictory, the existence of a Perfect Being is shown to be a necessary concept. The atheist would need to demonstrate that God’s existence is impossible (which itself is impossible), nonsensical (which is actually found in a worldview that postulates that things magically pop into existence without any cause), or self-contradictory. The only means that the non-believer has to disprove the necessity of God’s existence in my humble opinion is to show that there is a self-contradiction in God’s existence. Yet, it appears to me that there are greater self-contradictions in viewing the universe without the existence of God, thereby strengthening the necessity of a Perfect Being. The former is an impossible task, the middle is a task that some have attempted…and failed, and the third is inherently flawed.

Looking at this model from a different perspective, consider Alvin Plantinga’s take on Norman Malcolm’s argument, presented by Norman Geisler:

-

If God does not exist, his existence is logically impossible.

-

If God does exist, his existence is logically necessary.

-

Hence, either God’s existence is logically impossible or else it is logically necessary.

-

If God’s existence is logically impossible, the concept of God is contradictory.

-

The concept of God is not contradictory.

-

Therefore, God’s existence is logically necessary.[3]

Let’s unpack this argument. If God did not existence, his existence would be a logical impossibility like the existence of magical unicorns. If God does exist, then his existence would be a logical necessity—like the example of my parents’ existence as given above. Thus, God’s existence would be logically necessary if he exists or logically impossible if he does not exist. If God’s existence is impossible, then the idea of God is contradictory. God’s existence is not a contradiction; therefore, God is a logical necessity.

I personally like these arguments as I find the existence of God an absolute necessity. Non-theistic arguments often lead to bizarre absurdities which are at times irreconcilable. Christian theism is the most coherent of all worldview, thus the existence of the Christian God is a logical necessity. There is another take to this argument that demands consideration: the necessity of God found in possible worlds.

- Necessity of God Found in Possible Worlds.

A possible world is a hypothetical scenario that describes the various ways that the world could be. We live in the actual world, however the would could have been much different. With that in mind, consider Alvin Plantinga’s ontological argument from possible worlds.

-

It is possible that a maximally great being exists.

-

If it is possible that a maximally great being exists, then a maximally great being exists in some possible world. That is, God’s existence is not impossible (logically contradictory), so we can conceive of a world in which God does exist.

-

If a maximally great being exists in some possible world, then it exists in every possible world. (Otherwise, it would not be maximally great.)

-

If a maximally great being exists in every possible world, then it exists in the actual world.[4]

Let’s unpack Plantinga’s difficult argument. Nearly everyone would agree that it is at least possible that a maximally great being exists—that is, God. Since God’s existence is not impossible, then it is conceivable that God exists in some possible world. If it is possible that God exists in one possible world, then it is possible that he exists in every possible world including the actual world in which we live. Some will argue, “But yeah, it is possible that magical unicorns exist in some possible world. So, does that mean that magical unicorns must exist in this world?” Absolutely not! The existence of the magical unicorn is not a necessity. Since I am a contingent being, it is necessary in all possible worlds that I have a reason for my existence (by my parents or another set of parents). If God, being a necessary being, is possible in some possible world, he is possible in all possible worlds and is in fact found in the actual world. Confusing? Yes. But logically coherent? Absolutely!

Let’s now look at the last ontological argument of God’s necessity as it pertains to the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

- Necessity of God Found in Second Law of Thermodynamics.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that entropy increases as time progresses. Entropy is the disorder that occurs over time. Think of a wind-up toy. The wind-up toy is wound up and allowed to wind itself down. The winding down of the toy is the state of entropy. The same occurs with heat. Over time, heat cools until all heat is lost (i.e., heat death). The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that the universe is losing energy as it continues to exist. This will ultimately lead to a complete loss of heat unless there is an intervention from outside the universe. The following modus Tollens argument, presented by Groothius, notes how the Second Law of Thermodynamics argues for the finite nature of the universe and the necessity of God’s existence.

-

If the universe were eternal and its amount of energy finite, it would have reached heat death by now.

-

The universe has not reached heat death (since there is still energy available for use).

-

Therefore, (a) the universe is not eternal.

-

Therefore, (b) the universe had a beginning.

-

Therefore, (c) the universe was created by a first cause (God).[5]

Let’s unpack this argument. If it were possible that the universe is eternal with finite energy (which is observable), then the universe would have reached a heat death already. However, that has not occurred. Due to the absence of such an event, this proves that the universe is finite and had a beginning. If the universe had a beginning, the cause is most plausible to have been attributed to God. “Wait!” the skeptic may say. “Isn’t it possible that a multiverse gave birth to the universe?” Yes, it is possible. However, it has been shown in the BVG Theorem (named by its discoverers Borg, Vilenkin, and Guth) that all physical universes must have a finite past and an absolute beginning. So, the skeptic does nothing by arguing for a multiverse outside of pushing the necessity of God’s existence back a step or two.

Conclusion

It is true that these arguments are quite complex. But if one takes the time to evaluate and understand these versions of the ontological argument, I think one will find the necessity of God’s existence is rooted in a wealth of logical and philosophical certitude. Logically speaking, God’s existence is a necessity as it is demanded by logic and the data of causal relations in the actual world.

Original Blog Source: http://bit.ly/2npUHen

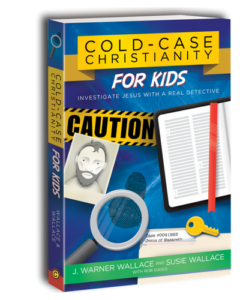

COLD-CASE CHRISTIANITY FOR KIDS

COLD-CASE CHRISTIANITY FOR KIDS FEARLESS FAITH SEMINAR

FEARLESS FAITH SEMINAR

ANSWERING ISLAM

ANSWERING ISLAM

http://bit.ly/2axGp8H

http://bit.ly/2axGp8H http://bit.ly/2aZGsGC

http://bit.ly/2aZGsGC http://bit.ly/2aZH1jK

http://bit.ly/2aZH1jK