By Daniel Merritt

Editor’s Note: Previously, we ran an article that featured Dr. Merritt’s research into the story concerning Voltaire’s prediction that the Bible would not be read in a century and the use of his facilities as a Bible repository. After running the article, Dr. Merritt came across further evidence verifying this story. This updated edition features eyewitness accounts that Voltaire’s own printing press was used to print copies of the Bible. As Dr. Merritt and I discussed in conversation, the evidence clearly backs up this story to the glory of God.

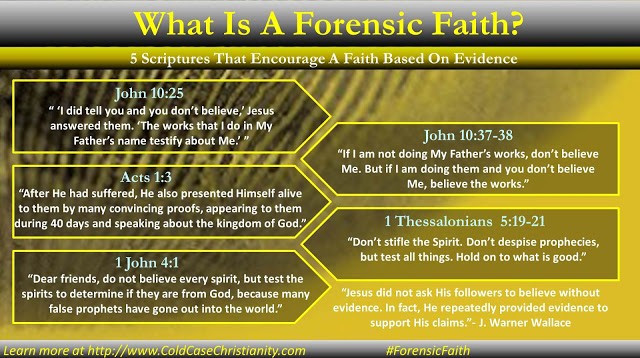

Often, stories are passed along in Christian circles without having the merits of their veracity examined. At times, the stories are shown to be little more than urban legends. At other times, a story’s facts become even more intriguing than the fictions ascribed to them. Such is the case with the story concerning Voltaire’s prediction that the Bible would no longer be read within a century, and the later ironic use of his home being used for Bible distribution after his passing. Dr. Daniel Merritt offers one of the best-researched defenses for the story’s authenticity that I have read. You are about to read the results of his research. We are all indebted to Dr. Merritt’s scholarship as we shall see, what I believe, to be the hand of God working to prove his Word as faithful despite the cynicism offered by a skeptical world. – Brian G. Chilton

A story which Christian apologists have told for years involves the French philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778). The story purports that Voltaire, in his voluminous writings against Christianity and the Bible, predicted in 1776, “One hundred years from my day, there will not be a Bible on earth except one that is looked upon by an antiquarian curiosity-seeker.” As the story alleges, within fifty years after his death, in an ironic twist of Providence, the very house in which he once lived and wrote was used by the Evangelical Society of Geneva as a storehouse for Bibles and Gospel tracts and the printing presses he used to print his irreverent works was used to print Bibles. The story has been used repeatedly through the years by Christians as an example of the enduring intrinsic quality of the Bible and the futility of those who oppose the Inspired Volume.

For years there have been those who dispute this story as to its validity. Humanists, rationalists, agnostics, and atheists have called it an apocryphal story fabricated by Christians to bolster their argument that the Bible is inspired and possesses an intrinsic quality that enables it to withstand attacks by unbelievers. David Ross wrote an article in the Journal of the New Zealand Association of Rationalists and Humanists, vol. 77, no. 1, Autumn 2004, entitled “Voltaire’s House and the Bible Society,” in which he went to great lengths to dismiss the story as having any real basis in fact. Ross contends the story has been either fabricated or it began as a misunderstanding and has spread. Ross’ article and others like it are of such a convincing nature that books like Introduction to the Bible by Norman Geisler and William Nix, left it out of later editions.[1]

The question to consider, is there any validity to the story? Did Voltaire ever make such a prediction? Is there proof that the home in which Voltaire once lived, that after his death, was used as a storehouse for Bibles? After much research, this writer has come to the conclusion that the story is true and that those who seek to discredit the story do so because it gives credence to the argument of apologists of God’s providential preservation of His Word.

Voltaire was born in Paris, France in 1694. As a philosopher, historian and free thinker, he became a most influential and prolific writer during what has been called the Age of Enlightenment. From the beginning, Voltaire had trouble with the authorities for criticisms toward the government. He twice served brief prison sentences in the Bastille for being critical of a Regent. His first literary work appeared in 1718. During his life he wrote more than 20,000 letters and some 2,000 pamphlets and books and was a successful playwriter. While a Deist, he vehemently opposed the Christian faith and wrote many rather scoffing works expressing his disdain for the faith and the Bible. His railings against Christianity are filled with poisonous venom, calling the Christian faith the “infamous superstition.”

Several examples of his slanderous words against the Christian faith and the Bible are cited.

In 1764 he wrote, “The Bible. That is what fools have written, what imbeciles commend, what rogues teach and young children are made to learn by heart” (Voltaire, Philosophical Dictionary, 1764). “We are living in the twilight of Christianity” (Philosophical Dictionary). In a 1767 letter to Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, he wrote: “Christianity is the most ridiculous, the most absurd, and bloody religion that has ever infected the world…My one regret in dying is that I cannot aid you in this noble enterprise of extirpating the world of this infamous superstition.”[2] Voltaire ended every letter to friends with “Ecrasez l’infame” (crush the infamy — the Christian religion). In his pamphlet, The Sermon on the Fifty (1762) he attacked viciously the Old Testament, biblical miracles, biblical contradictions, the Jewish religion, the Christian God, the virgin birth and Christ’s death on the cross. Of the Four Gospels he wrote, “What folly, what misery, what puerile and odious things they contain [and the Bible is filled] with contradictions, follies, and horrors”[3]. Voltaire regarded most of the doctrines of the Christin faith – the Incarnation, the Atonement, the Trinity, Communion – as folly and irrational.[4] And finally, “To invent all those things [in the Bible], the last degree of rascality. To believe them, the extreme of brutal stupidity!”[5]

Many more such quotes could be cited as to Voltaire’s disdain for Christianity, but those will suffice. Voltaire’s writings were so divisive that in 1754 Louis XV banned him from Paris. Relocating in December 1754 to Geneva, Switzerland, he purchased a beautiful chateau called Les Delices (The Delights). He lived there for five years until 1760 when as the result of his antagonistic writings and plays attacking Christianity, he was virtually driven from Geneva by the Calvinist Reformers. To escape the pressure from the Calvinists, Voltaire moved across the border to Ferney, France, where the controversial Frenchmen lived for eighteen years until the end of his life in 1778 at age 83. He continued to write until his hand was stilled in death.

Now the question arises as to the veracity of what some call an “apocryphal story.” While Voltaire’s disdain for the Bible is evident, did he ever make such a prediction and did any Bible Society ever use either of his residences, from where he wrote his blasphemous words against the Bible and the Christianity, as a warehouse to store Bibles? The answer to that question is an emphatic, “YES!”

The second part of the story will be dealt with first.

In August 1836, only fifty-eight years after Voltaire’s death, Rev. William Acworth of the British and Foreign Bible Society saw with his own eyes Voltaire’s former residence in Geneva, Switzerland, Les Delices, being used as a “repository for Bibles and Religious tracts.” The house at this time was occupied by Colonel Henri Tronchin (1794-1865), who served as the president of the Evangelical Society of Geneva from 1834-39.[6] The Tronchin family had long had associations with Voltaire that could be traced back to the 18th century. One of Henri Tronchin’s ancestor’s, Francis Tronchin, was Voltaire’s doctor. The Tronchin’s were prominent and wealthy residents of Geneva and even helped finance Voltaire in the publishing of some of his works.[7]

While the Tronchin family was prominent and wealthy citizens of Geneva, they were not predominately spiritual. However, though it is not known exactly when, Henri Tronchin came to faith in Christ and embraced Protestantism. Studying literature at the Academy of Geneva, he later served as artillery captain on horseback in the Dutch army. Eventually rising in ranks to lieutenant-colonel of artillery, he married in 1824. A superb organizer and a great leader, he helped found the Evangelical Society of Geneva (c1833). He served as president of the Society from 1834 to 1839. Born 100 years after Voltaire, and occupying the former home of the infamous infidel, Tronchin used the spacious house to store Bibles and Gospel tracts. Rev. William Acworth of Queens College, Cambridge, appointed an agent of the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1829, was an eye witness to the stored Bibles and Gospel tracts.[8]

In The Missionary Register for 1836 of the BFBS, Acworth is recounting his travels in the spread of the Gospel. Having traveled over 2,000 miles in France on the business of the Society, in the summer of 1836 his travels took him to Switzerland in August of that year. Acworth recounts:

I went through Geneva, and was much refreshed by meeting the Committee of the Evangelical Society, with whose proceedings and objects I was so much gratified, that I wrote to this Society to make a liberal grant of 10,000 copies of the French Scriptures to promote the objects of that Society. Our committee have only granted 5,000; but I have no doubt they will, err long, send the other 5,000. Before I left Geneva, my friend observed. “Probably you will like to see the house where Voltaire lived, and where he wrote his plays.” Prompted by the spirit of curiosity, so characteristic of an Englishman, to visit the house of the celebrated infidel, I was about to put on my hat to walk into the county, when he said, “It is not necessary you should put on your hat” and he introduced me over the threshold of one room to another, and said, “tis the room where Voltaire’s play were acted for the amusement to himself and his friend.” And what was my gratification in observing that that room had been converted into sort of Repository for Bibles and Religious Tracts. Oh! my Christ Friends, that the spirit of infidelity had been there, to witness the results of other vaticinations [acts of prophesying] respecting the downfall of Christianity! I know that Voltaire said, that he was living “in the twilight of Christianity” but blessed be God! It was the twilight of the morning, which will bring on the day of universal illumination.[9]

Only fifty-eight years after his death the former home of Voltaire in Geneva, Switzerland, was indeed serving as a storehouse for Bibles and Gospel tracts. While the Evangelical Society of Geneva did not actually purchase the house, Henri Tronchin, president of the Society, resided in the house, and used some of the rooms to store Bibles which Voltaire so vehemently opposed and prophesied Christianity’s downfall! Yes, an ironic twist of divine Providence.

Let it also be noted, only sixteen years after Voltaire’s death, in 1794, the presence of the Bible began making in-roads in the town where he spent the last eighteen years of his life, Ferney, France. On the very printing presses which Voltaire employed to print his irreverent works was used to print editions of the Bible and which were printed on paper that “been especially made for a superior edition of Voltaire’s works. The Voltaire project failed, and the paper was bought and devoted to a better purpose [of printing Bibles]!”[10]

In the book Letters from an Absent Brother, by Daniel Wilson, Bishop of Calcutta, which chronicles his travels through parts of Netherlands, Switzerland, Northern Italy, and France, he writes to his sister from Geneva on Wednesday evening, seven o’clock, October 1, 1823, concerning the distribution of Bibles in the town where Voltaire once lived: When I arrived at Paris, one of the first things I heard was that a Bible society had been established at Ferney, chiefly by the aid of Baron de Stael. What a noble triumph for Christianity over this daring infidel. One of the first effect of the revival of true religion or even of sound learning in France, I should think would be to lower the credit of this profligate, crafty, superficial, ignorant, incorrect writer. What plea can wit or cleverness, or the force of satire or the talent of ridicule or a fascinating style, or the power of brilliant description, form, in a Christian country, for a man who employed them all, with a bitterness or ferocity, of mind amounting to almost madness, against the Christian religion and the person of our Saviour.[11]

That a Bible society had been established in Ferney, France to help financially in the printing of Bible’s in the town where Voltaire once resided, is confirmed in the 1824 Report of the Protestant Bible Society at Paris containing the following sentence: A newly established branch at Ferney formerly the residence of Voltaire, has sent its first remittance, a sum of 167 francs.[12]

Further proof that the printing presses Voltaire once used to print his blasphemous works is contained in a transcript from the Quarterly Papers of the American and Foreign Bible Society of 1837: A Bible Society was some years since established at Ferney, once the residence of Voltaire—the prince of infidels. This noble enterprise for the propagation of the Christian religion is said to have commenced by Baron de Stael, and a few zealous Christians in that place. In the history of Bible Societies, this is truly a memorial event. That the antidote should issue from the very spot where the poison of infidelity for so many years disseminated; and the advocates of Christianity should in that very place print and circulate the sacred volume, as a sufficient shield against misrepresentations sophistry which he had there assailed divine revelation, are the events which the brilliant Frenchman would have pronounced impossible.[13]

In 1845 Bibles were still being printed on printing presses Voltaire once employed in Ferney, France. The 1846 anniversary address of The American and Foreign Bible Society, Rev. Charles G. Sommers gave a stirring report on how the Bible was making penetration into various places around the world. When speaking about the Scriptures advancements in countries around the world (including France) in the previous year of 1845, Rev. Sommers stated,

“Much has indeed been accomplished, but much more remains to be done for the millions who are still without God, without Christ, and without hope in the world. It is true, indeed, and we thank God, that in nine years this Society has printed one million of books in forty-nine different languages, but hundreds of millions must be distributed among the famishing myriads of our race. By what other means can we hope to arrest the progress of infidelity and Romanism; now marching in triumph over the fields of our fair inheritance? When Pythagoras and Confucius were filling Europe and Asia with heresies, God raised up Ezra, the prophet, to compile and publish the books of the Old Testament, as an antidote to their delusions. And when Voltaire, Diderot, D’Alembert and Rousseau were laboring to crush the bleeding cause of Christ, God raised up against them the standard of the British and Foreign Bible Society; and it is a cause for grateful exultation that the same printing press which was employed to scatter the blasphemous tracts of the prince of French philosophers, has since been used at Ferney (France), to print the Word of God. The black confederacy raised their bulwarks to impede the march of truth, but they would have been equally successful, had they forged chains to bind the lightning, that cometh out of the east, and shineth even unto the west, as the precursor of the coming of the Son of man. Voltaire boasted that he had seen the twilight of Christianity, and that the pall of an endless night would soon cover it forever. Yes, sir, he did see the twilight, but he was mistaken as to the hour of the day—it was the twilight of morning, pouring its effulgence over the brim of the horizon of the nineteenth century, which he mistook for the rays of a setting sun.”[14]

Having established that Bibles were actually stored in Voltaire’s former Geneva residence and were being printed on printing presses he once employed in Ferney, France, did he ever make such a prediction that one hundred years after his death the Bible would no longer be read? A man who wrote 20,000 letters in his lifetime, it would be impossible to know all the statements he wrote or spoke. However, it was generally acknowledged and understood by those near the time Voltaire lived that he had made such a prediction either verbally or in writing which may no longer exist. Rev. Acworth in 1836, only fifty-eight years after Voltaire’s death, referred to the infidel’s “vaticinations [act of prophesying] respecting the downfall of Christianity! Such a remark indicates it was common knowledge that such a bold prediction had been made by Voltaire. In 1849, only seventy-one years after Voltaire’s death, William Snodgrass, an officer of the American Bible Society, stated in the giving of ABS’s annual report that “the committee had been able to redeem their pledge by sending $10,000 to France, the country of Voltaire, who predicted that in the nineteenth century the Bible would be known only as relic of antiquity.”[15] Again, such a remark indicates it was commonly acknowledged that Voltaire had made such a prediction.

Found in an interpretative book on many of the works of Voltaire published in 1823, only forty-five years after his death, the author, a contemporary of the Frenchman, details the fact that he brutishly sought to inspire contempt for the Christian faith and saw himself more influential than Martin Luther and John Calvin! Voltaire wanted a “religion to be without code, without laws, without dogma, without authority” and “laughed all these Christians who believed their religion was truly divine.” The author states that Voltaire in his fight against Christianity would stop “at nothing to annihilate” the Christian faith.[16] It is obvious those in Voltaire’s day believed his efforts were for the purpose of dismantling Christianity.

While this writer could not find the exact quote that usually accompanies the story, similar quotes could be found. In an 1855 biography of Voltaire, the author quotes him as stating in a letter to a friend, “It is impossible that Christianism survives.”[17] In an effort to assist in bringing about what he perceived would hurry the demise of “Christianism,” in 1776, at age 82, Voltaire brought to a culmination his disdain for the Bible when he published La Bible Enfin Expliquée (The Bible Fully Explained).[18] The two-volume work was Voltaire’s commentary on the whole Bible. His purpose in writing was to “make the whole building [of Christianity] crumble.”[19] Writing with feigned credulity in a satirical and scoffing manner, he wrote viciously, mockingly critical and skeptically of practically every book and verse in the Bible. His sought to expose, as he saw it, the foolishness and irrationality of belief in the Bible. Of his massive tome, in which he derided the Bible on every page, he stated, “The subject is now exhausted: the cause is decided for those who are willing to avail themselves of their reason and their lights, and people will no more read this [Bible].”[20]

From such an arrogant declaration it is clear Voltaire delusionally believed as a result of his La Bible Enfin Expliquée, he had struck a death blow to the Bible’s believability and the sun was setting on the Book’s influence and in time the Volume would become irrelevant. However, instead of the Bible becoming irrelevant and no longer believed, the Inspired Volume begins to increase in circulation… his former house, only fifty-eight years after his death, being used as a storehouse to house Bibles and Gospel tracts and printing presses he once employed to print his anti-Christian sentiments was being used to print Bibles!

Like all stories that are repeated over the years, the exact details and wording may vary, but it seems clear the key components of the story are very much true. The story of Voltaire serves as an example and a reminder that the foolish predictions and efforts of man to extinguish the Bible will come to naught. No skeptic’s scoffing hammer has ever made a dent in the Eternal Anvil of God’s Word. To those who attempt to do so, Jesus emphatically declares, “Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away” (Matthew 24:35).

Amen!

Notes

[1] Norman Geisler and William Nix, Introduction to the Bible, (Chicago: Moody Press, 1968), 124.

[2] Sarah Coakley, Faith, Rationality and the Passions, (MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2012), 37.

[3] Voltaire, Trans. Joseph McCabe, Selected Works of Voltaire, “The Sermon on the Fifty,” (London: Watts & Co., 1911), 178-180.

[4] Voltaire, ed. H.I. Wolff, Philosophical Dictionary, “Arius,” (New York, 1924), 253.

[5] Quote of Voltaire from his work God and Man, chapter xliv, found in James Parton, Life of Voltaire, Vol. II, (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co, 1881), 429.

[6] Stelling-Michaud, Suzanne, Le livre du Recteur de l’Académie de Genève (1559-1878) (Vol 6). Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1980, 72; also, Jean-Yves Carluer, “Henri Tronchin,” December 16, 2017, http://le-blog-de-jean-yves-carluer.fr/2017/12/16/henri-tronchin/ (Accessed March 12, 2019). In 1929 the Les Delices property was purchased by the city of Geneva, and now houses the Institute et Musee Voltaire, a museum founded in 1952 dedicated to the life and works of Voltaire.

[7] On Voltaire’s relations with the Tronchin family, see Deidre Dawson, Voltaire’s Correspondence: An Epistolary Novel (New York: Peter Lang, 1994), 101–126; also, George Valbert, “The Genevese Councilor François Tronchin and his relations with Voltaire”, The Revue des Deux Mondes, 1895, 205-216

[8] William Canton, A History of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 1845-1926, (London: J. Murray, 1903), 98.

[9] The Missionary Register for 1836, William Acworth, “Bible Notices in Switzerland and Italy,” (London: L&G Seeley, 1836), 352.

[10] The Gentleman s Magazine, July, August, September 1794; Samuel Bagster, The Bible of Every Land (London, 1860), 167. Curiously enough, Bibles were printed on paper, which, according to Hannah More, had been specially made for a superior edition of Voltaire’s works. The Voltaire project failed, and the paper was bought and devoted to this better purpose. Monthly Extracts, 1848, August, p. 793.

[11] Daniel Wilson, “Letters from an Absent Brother, (London, 1824), 187.

[12] Report of the British and Foreign Bible Society, Vol. 7, 1822, 1823, 1824, (London: J.S. Hughes, 1824), 17-18.

[13] Quarterly Papers of the American and Foreign Bible Society, No 11, New York, July 1837, “Bible Society at Ferney,” 21-22.

[14] Ninth Annual Report of the American and Foreign Bible Society, Presented at New York, May 15, 1846, (New York: John Gray, 1846), 48.

[15] Annual Report of the American Bible Society, 1849, Appendix, 98.

[16] Claude Francois Nonnottee, Erreurs de Voltaire, (Paris, 1823), 285-305.

[17] Eugene Noel, Voltaire, (Paris: F. Chamerot, 1855), 99.

[18] Arnold Ages, “The Technique of Biblical Criticism: An Inquiry into Voltaire’s Satirical Approach in La Bible Enfin Expliquée,” A Quarterly Journal in Modern Literatures, September 6, 2013, 67-79.

[19] Voltaire, La Bible Enfin Expliquée, (Alondres), 1776, 2.

[20] Voltaire, La Bible Enfin Expliquée, (Alondres), 1776; also; James Parton, Life of Voltaire, Vol. II, (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co, 1881), 543.

Daniel Merritt, a native of Sanford, NC, received his Ph.D. in Ministry from Luder-Wycliffe Seminary and his Th.D. from Northwestern Seminary. He also received his M.Div. from Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and studied philosophy and religion at Campbell University. Dr. Merritt has pastored six churches in North Carolina, teaches at the Seminary Extension of the Southern Baptist Convention, and is currently the Director of Missions for the Surry Baptist Association in Mount Airy, North Carolina. Dr. Merritt has written several books including A Sure Foundation: Eight Truths Affirming the Bible’s Divine Inspiration; Writings on the Ground: Eight Arguments for the Authenticity of John 7:53-8:11; and Bitter Tongues, Buried Treasures.

Original Blog Source: http://bit.ly/2YNCQUY