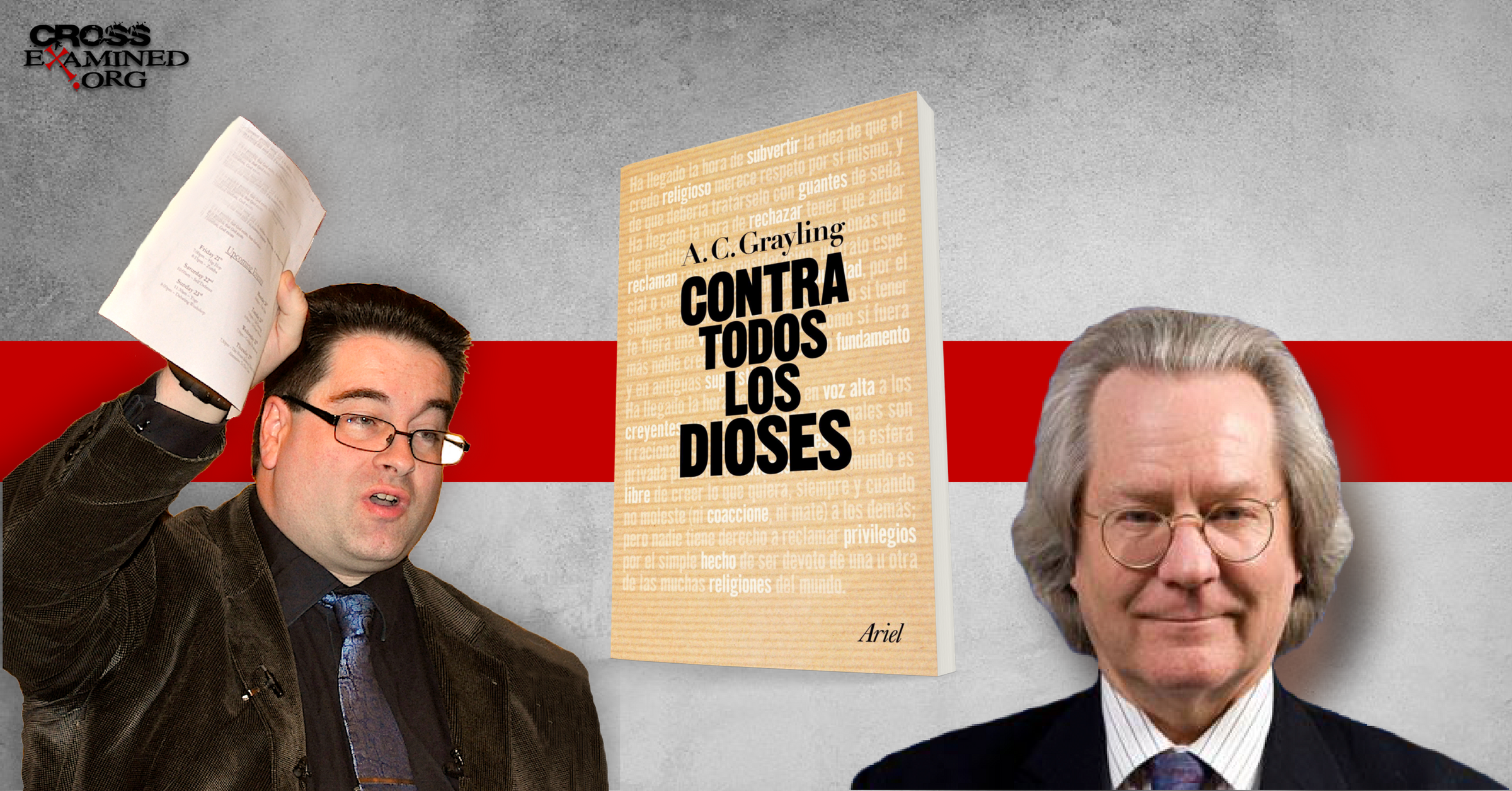

Por Peter S. Williams

Contra Grayling

Una respuesta cristiana a “Contra todos los dioses” (Oberon Books, 2007)

Por Peter S. Williams (MA, MPhil)

A.C. Grayling, profesor de Filosofía en el Birbeck College de la Universidad de Londres, comienza su autodenominada polémica contra la religión con una pregunta y una respuesta: “¿Merece respeto la religión? Yo sostengo que no merece más respeto que cualquier otro punto de vista, y no como la que más lo merece”[1]. A partir de entonces, la crítica de Grayling a “todos los dioses” es principalmente un asalto a dos caras sobre a) la respetabilidad intelectual de la fe y b) la respetabilidad ética de los creyentes e instituciones religiosas como tales.

Con respecto a la respetabilidad intelectual de la fe, Grayling piensa que: “Algunos en mi propio lado del argumento aquí cometen el error de pensar que la disputa sobre las creencias sobrenaturales es si son verdaderas o falsas. La epistemología nos enseña que el punto clave es sobre la racionalidad”[2]. Mientras que la ‘epistemología’ enseña la distinción entre la verdad y la racionalidad de una creencia (considere la obra de Alvin Plantinga sobre la diferencia entre las objeciones de facto y de jure al teísmo cristiano y cómo los cristianos deberían responder a estos diferentes tipos de objeciones[3]), esta distinción no justifica la afirmación de que el asunto de la verdad tome la última palabra. Dios puede existir incluso si es irracional creer en Dios (así como cierto acusado podría ser culpable incluso si el jurado fuera irracional para condenarlo sobre la base de los datos disponibles para ellos) — una observación que hace menos interesante la acusación de irracionalidad y, por lo tanto, menos fundamental que la acusación de falsedad. Además, si uno tiene una creencia justificada de que el teísmo sea verdadero, con seguridad se justificaría pensar que la creencia teísta fuera racional (así como si alguien tuviera una buena razón para condenar a un acusado determinado, tendría una buena razón para considerar la propia creencia en su culpabilidad por ser racional).

Sin embargo, Grayling reformula incluso una objeción de facto tradicional al teísmo como el problema lógico del mal como una objeción de jure a su respetabilidad racional: “Creer en la existencia de (digamos) una deidad benevolente y omnipotente frente a los cánceres infantiles y las muertes masivas en tsunamis y terremotos [es un ejemplo de] irracionalidad grave”[4]. Grayling no hace nada para elaborar un argumento real en este sentido, y parece ignorar el hecho de que: “Los filósofos de la religión han puesto serias dudas sobre si existe alguna incoherencia que implique las proposiciones apropiadas sobre el mal y las supuestas propiedades de Dios”[5]. Como explica William L. Rowe:

“Algunos filósofos han sostenido que la existencia del mal es lógicamente inconsistente con la existencia del Dios teísta. Nadie, creo, ha logrado establecer una afirmación tan extravagante. De hecho, concediendo incompatibilismo, hay un argumento bastante convincente para la opinión de que la existencia del mal es lógicamente consistente con la existencia del Dios teísta”[6].

La religión es…

¿Cuál es, más precisamente, el objetivo de Grayling? Grayling afirma (y como veremos, Grayling es muy bueno simplemente afirmando cosas) que:

“por definición, una religión es algo centrado en la creencia de la existencia de organismos o entidades sobrenaturales en el universo; y no meramente en su existencia, sino en su interés por los seres humanos en este planeta; y no solo su interés, sino su interés particularmente detallado en lo que los humanos usan, lo que comen, cuando lo comen [etc.][7]

Se supone que esta lista cada vez más específica de características pretende constituir una especie de argumento demasiado obvio para ser digno de escribir sobre los absurdos de pensar que Dios estaría interesado en su creación (si él se toma la molestia de existir). Sin embargo, también tiene el efecto de sugerir que Grayling nunca ha oído hablar de budistas no-teístas, o deístas, o aristotélicos, o panteístas, o personas que son naturalistas salvo por la creencia de que su mente es más que su cerebro (para el humano el espíritu o el alma de un vegano ciertamente cuenta como una entidad sobrenatural interesada en los seres humanos y en lo que comen). De hecho, es notoriamente difícil definir la religión. Como observó Eric S. Waterhouse: “Nunca se ha encuadrado una definición de religión que afecte a todos los aspectos de la vida, y ninguna ha encontrado incluso una medida considerable de aceptación general”[8].

Apologistas religiosos y creyentes ordinarios

Grayling se queja de que:

“Los apologistas de la fe son una comunidad evasiva que busca evitar o desviar las críticas deslizándose detrás de las abstracciones de la teología superior, un dominio envuelto en neblina de palabras largas, distinciones superfinas y sutilezas vagas, en algunas de las cuales Dios no es nada… y ni siquiera existe… Pero la religión no es teología; es la práctica y el punto de vista de la gente común en la mayoría de los cuales las creencias y supersticiones sobrenaturales fueron inculcadas como niños cuando no podían evaluar el valor de lo que se vendía como una visión del mundo; y es la falsedad de esto y sus consecuencias para un mundo sufriente lo que los críticos atacan”[9].

Esta queja requiere un poco de desenredo. Ciertos apologistas son criticados por defender creencias (como la inexistencia de Dios) que de ninguna manera representan las creencias del creyente ordinario. No tengo ningún problema en criticar a tales creencias, o tales apologistas. Los apologistas en general son criticados por defender la fe usando: a) abstracciones, b) palabras largas que los no expertos no entienden, c) distinciones súper finas y d) vagas sutilezas. Sin embargo, las abstracciones, el lenguaje técnico, las distinciones finas e incluso las vagas sutilezas son la base natural en el oficio de los filósofos, científicos y, de hecho, el de todos los estudiosos que defienden puntos de vista controvertidos sobre el mundo. El mismo Grayling no está por encima de usar abstracciones (“religión”, así como el comportamiento de sus seguidores, es una “abstracción” en la polémica de Grayling); palabras largas que los no expertos no entienden (prueba con “espesado crepúsculo”[10] para el tamaño); distinciones súper finas (como la que existe entre el ateísmo y el naturalismo); o sutilezas vagas (en cuya categoría uno podría poner toda la insinuación de un argumento en el libro de Grayling). Los apologistas deben, por supuesto, hacer todo lo posible para fundamentar sus abstracciones en datos suficientes con una lógica convincente, para explicar su terminología para los no iniciados, para evitar distinciones que son tan finas y que se conviertan en “distinciones sin diferencia” (distinciones que son precisamente lo suficientemente finas son una marca de excelencia filosófica) y que retengan sutilezas vagas para temas que son vagos y/o que realmente requieren una comprensión sutil. Por el tono de Grayling uno imagina que acusaría a todos los apologistas religiosos de no cumplir con estas responsabilidades intelectuales. Lamentablemente, no proporciona ninguna evidencia para respaldar lo que yo consideraría una generalización apresurada en el mejor de los casos y un hombre de paja en el peor de los casos.

La experiencia personal me lleva a pensar que Grayling se sorprendería de lo mucho que la teología y la apologética son parte integrante de la vida y la fe del creyente religioso “común”. Una vez más, es interesante observar cómo Grayling concentra su atención en las supuestas consecuencias negativas de toda religión para un mundo que sufre, pero dice muy poco acerca de la supuesta falsedad de todas las creencias sobre lo sobrenatural. Por último, no creo que el supuesto de Grayling acerca de las creencias sobrenaturales que se inculca en los niños que no pueden evaluar el valor de lo que se les está vendiendo como una visión del mundo nazca por la evidencia. Por ejemplo, como en el 2005 se reveló en el cuestionario de Dare to Engage (Atrévete a participar), una gran proporción de estudiantes de nivel A que han pasado toda su vida criados en hogares religiosos y comunidades que profesan no estar decididos a aceptar esa tradición de fe.

Los males de la religión

Grayling defiende el tono polémico de su libro: “Si el tono de la polémica aquí parece combativo, es porque la competencia entre puntos de vista religiosos y no religiosos es tan importante, un asunto literalmente de vida o muerte, y no puede haber contemporización”[11]. Pensé que, cuanto más importante sea el tema, más importante sería alejar a aquellos con quienes no estás de acuerdo insultándoles. Y como Grayling observa: “El debate se ha vuelto acerbo…”[12]. Uno podría pensar que un debate mordaz implicará más calor que luz. De hecho, Grayling reconoce que: “Podríamos mejorar el respeto que otros nos otorgan si somos amables, considerados… veraces… aspirantes al conocimiento… buscadores del bien de la humanidad, y cosas por el estilo” y admite (de acuerdo al gusto de Richard Dawkins) que: “Ningún conjunto de características tiene alguna conexión esencial con la presencia o ausencia de sistemas de creencias específicos, dado que hay cristianos buenos y desagradables, musulmanes agradables y desagradables, ateos agradables y desagradables”[13]. Sin embargo, Grayling está interesado en: “Criticar las religiones como sistemas de creencias y como fenómenos institucionales que, como lo atestiguan el lúgubre historial y el presente, han causado y continúan causando mucho daño en el mundo, sea cual sea el bien que se pueda reclamar para ellos además”[14]. Esta es una crítica extraña que equivale a decir que incluso si la religión hace abrumadoramente más bien que mal, es razonable criticar a la religión sobre la base del daño que causa. Eso es más bien como conducir un debate sobre los méritos del transporte público al señalar que los trenes a veces chocan, mientras se está preparado para reconocer que los trenes son mucho más seguros que los automóviles.

Grayling señala que “no se han librado guerras, ni se han llevado a cabo pogromos, ni se han quemado personas en la hoguera, sobre teorías rivales en biología o astrofísica”[15]. Esto puede ser, estrictamente hablando, la verdad; sin embargo, lo que uno hace de esta observación más bien depende de la visión que uno tenga de diversos actos que han sido inspirados y/o justificados por varias teorías científicas (¿alguien por el racismo científico, la eugenesia o el aborto?). Para responder que hay una diferencia entre una ciencia que se usa o se tuerce para justificar algo y la ciencia en realidad justificándolo es abrir la puerta para que los creyentes religiosos hagan una defensa paralela de la religión.

Sobre el tema específico de la incineración, mencionado por Grayling (un tema que debería ser entendido dentro de su contexto histórico), el científico social Philip J. Sampson observa que: “El número de enjuiciamientos por brujería a menudo se ha exagerado mucho, y nosotros ahora sabemos que la Inquisición tendió a moderar en lugar de incitarlos”[16]. El historiador William Monter escribe que “la suavidad de los juicios inquisitoriales sobre la brujería contrasta notablemente con la severidad de los jueces seculares en todo el norte de Europa”[17]. De hecho, según el historiador Hugh Trevor-Roper: “En general, la iglesia establecida se oponía a la persecución [de las brujas]”[18].

Con Keith Ward, creo que está claro que: “La religión causa un poco de mal y un poco de bien, pero la mayoría de la gente, frente a la evidencia, probablemente estará de acuerdo en que hace mucho más bien que mal, y que estaríamos mucho peor como especie sin religión”[19]. Esto no es para negar que los cristianos (incluso los cristianos ‘nacidos de nuevo’ de creencias religiosas intrínsecas más que extrínsecas) han hecho muchas cosas terribles a lo largo de la historia (somos, después de todo, pecadores), pero como Ward argumenta: “Hay algunas creencias religiosas inequívocamente malvadas 2025 también hay algunas creencias no religiosas inequívocamente malvadas. Lo que hace que las creencias sean malas no es la religión, sino el odio, la ignorancia, la voluntad de poder y la indiferencia hacia los demás”[20]. La religión no debería ser más atacada con el pincel de sus peores ejemplos que la política o la ciencia. Como dijo William Wilberforce: “Del mismo modo que no descartaríamos la libertad porque la gente abuse de ello, ni el patriotismo, ni el coraje, ni la razón, el discurso y la memoria -aunque todos abusaron– no más deberíamos eliminar la verdadera religión porque los egoístas la han pervertido”[21].

De hecho, algunas formas de religión, al menos, hacen un gran bien. Como advierte el humanista secular Richard Norman:

“Reconozco que la religión ha inspirado no solo a algunos de los peores sino también a algunos de los mejores logros humanos. Ha inspirado movimientos sociales y políticos para mejorar la suerte de los seres humanos, como en la abolición de la trata de esclavos, el movimiento por los derechos civiles, las campañas por la paz, contra la pobreza y la hambruna en el mundo. Ha inspirado muchos de los mayores logros culturales y artísticos… Presentar la religión y sus obras bajo una luz totalmente negativa sería, en mi opinión, irremediablemente desequilibrado”[22].

Todo esto a un lado, como observa Tom Price:

“Me parece que todo el argumento compromete lo que podríamos llamar ‘El culpable por la falacia de asociación’. Lo cual supone que la religión es incorrecta y no creíble porque algunas personas se radicalizan. Esa es solo una mala estructura lógica. Si la religión conduce a la violencia o no, no afecta en si esta es verdad o no. La resurrección de Jesús como un evento, la evidencia que se le presenta y sobre la cual se le pide que base la creencia cristiana, es completamente independiente del comportamiento de sus seguidores. Alister McGrath dio el ejemplo de los médicos: “Solo porque vimos lo que Harold Shipman hizo, no significa que decimos que todos los médicos son malos”[23].

¿Debería la fe ganarse el respeto?

De acuerdo con Grayling:

“Es hora de negarse a caminar de puntillas en torno a personas que reclaman respeto… sobre la base de que tienen una fe religiosa… como si fuera noble creer en afirmaciones sin fundamento y antiguas supersticiones. No tiene sentido. La fe es un compromiso con la creencia contraria a la evidencia y la razón… creer en algo frente a la evidencia y en contra de la razón, creer en algo por fe, es innoble, irresponsable e ignorante, y merece lo contrario al respeto”[24].

De todo corazón estoy de acuerdo en que un compromiso con la creencia contraria a la evidencia y la razón es innoble. De todo corazón estoy en desacuerdo con que esta sea una descripción precisa de mi fe cristiana. La descripción de fe de Grayling comete la falacia del hombre de paja. La falacia del hombre de paja se comete “cuando un argumentador distorsiona la posición de un oponente con el propósito de hacerlo [más fácil] de destruir, refuta la posición distorsionada, y concluye que la opinión de su oponente es por lo tanto demolida”[25]. La definición de fe de Grayling es un hombre de paja porque aunque las creencias irracionales son fáciles de criticar, pocos cristianos aceptarían la definición fácil de crítica de Grayling de “fe” como una que se aplica a ellos. Ciertamente no es como la Biblia describe la fe. Considera lo que la Biblia dice acerca de la evidencia y la razón:

- El cosmos es la creación de un Dios racional que hizo a los humanos en su propia “imagen” (Génesis 1:27).

- Dios dice a los seres humanos: “Estemos a cuentas” (Isaías 1:18).

- El profeta Samuel se puso de pie delante de Israel y dijo: “Voy a confrontarte con evidencias delante del Señor” (1 Samuel 12:7).

- Según Jesús, el mandamiento más grande incluye el requisito de “amar al Señor tu Dios… con toda tu mente ” (Mateo 22:37).

- Jesús dijo: “Créanme cuando digo que estoy en el Padre y que el Padre está en mí; o al menos crean en la evidencia de los milagros mismos” (Juan 14:11).

- Pablo escribió acerca de “defender y confirmar el evangelio” (Filipenses 1:7) y “razonó… desde las Escrituras, explicando y probando” (Hechos 17:2-3).

- A los cristianos se les ordena: “Siempre estén preparados para dar una respuesta a todos los que les piden que den la razón de la esperanza que tienen… con gentileza y respeto” (1 Pedro 3:15).

El griego traducido como “razón” es “apología“, de lo cual obtenemos la palabra “apologética”, que significa “defensa razonada”. La apologética es el arte de dar una defensa razonada para el cristianismo. El Nuevo Testamento describe la apologética como parte de la “guerra espiritual” en la que los cristianos “derriban argumentos y toda altivez que se levanta contra el conocimiento de Dios…” (2 Corintios 10:5). La Apologética utiliza la erudición de muchos tipos, que implican un compromiso con las “leyes de la razón” en el corazón de la filosofía. Como C.S. Lewis escribió: “La buena filosofía debe existir, si por ninguna otra razón, porque la mala filosofía debe ser respondida”[26]. Tom Price observa que: “Cuando el Nuevo Testamento habla positivamente de la fe, solo usa palabras derivadas de la raíz griega [pistis] que significa “ser persuadido”[27]. Si bien es cierto que Colosenses 2:8 advierte a los cristianos de no ser “cautivos por la filosofía y el engaño vacío según la tradición humana… y no según Cristo”, esta advertencia “no es una prohibición contra la filosofía como tal, sino contra la falsa filosofía… De hecho, Pablo advierte contra una filosofía falsa específica, una especie de gnosticismo incipiente… el artículo definido “esto” en [el] griego indica una filosofía particular”[28].

Sorprendentemente, Grayling hace referencia a la historia del Nuevo Testamento de la incredulidad de Tomás (Juan 20: 24-31), que se negó a aceptar el testimonio de diez amigos acerca de la realidad de la resurrección de Jesús (pero que aceptó esta realidad después de su propio encuentro con la resurrección) — como apoyo a su redefinición de la fe de hombre de paja. Sin embargo, en esta historia, Jesús elogia a las personas que creen sin tener que ver por sí mismos, no aquellos que creen sin evidencia, y mucho menos en contra de la evidencia. ¡Antes de que Jesús se ofreciera a Tomás para un examen personal, ¡a Tomás no se le pedía que creyera sin pruebas! Además, la razón por la cual Juan da para contar estos eventos es porque son evidencia de la verdad del evangelio (Juan 20: 30-31).

Grayling afirma que: “Es asunto de todas las doctrinas religiosas mantener a sus devotos en un estado de infancia intelectual (¿de qué otra manera mantienen los absurdos aparentemente creíbles?)”[29]. Incapaz de imaginar a una persona intelectualmente madura que no piense que toda religión es absurda, Grayling deduce que todos los creyentes religiosos deben ser intelectualmente inmaduros. Al parecer, no le preocupa la observación de que al menos algunos creyentes religiosos son pensadores intelectualmente maduros. Por ejemplo, el filósofo secular John Gray hace el siguiente cumplido a los eruditos religiosos contemporáneos:

“Hoy no se puede entablar un diálogo con pensadores religiosos en Gran Bretaña sin descubrir rápidamente que, en general, son más inteligentes, mejor educados y notablemente más librepensadores que los incrédulos (como los ateos evangélicos aún se describen de manera incongruente)”[30].

Según Gray, las acusaciones como las de Grayling dicen más sobre el acusador que sobre el acusado:

“Karl Marx y John Stuart Mill insistieron en que los religiosos morirían con el avance de la ciencia. Eso no ha sucedido, y no existe la perspectiva más remota de que esto suceda en el futuro previsible. Sin embargo, la idea de que la religión puede ser erradicada de la vida humana sigue siendo un artículo de fe entre los humanistas. A medida que la ideología secular se vierte en todo el mundo, quedan desorientados y boquiabiertos. Es esta dolorosa disonancia cognitiva, creo, lo que explica el rencor particular y la intolerancia de muchos pensadores seculares. Incapaces de dar cuenta de la irrefrenable vitalidad de la religión, solo pueden reaccionar con horror puritano y estigmatizarla como irracional”[31].

Según los informes, A.J. Ayer estaba “desconcertado por el hecho de que los filósofos a quienes respetaba intelectualmente, como Michael Dummett, tuvieran creencias religiosas”, pero al menos “tenía que admitir que ese era el caso”[32]. James Lazarus ha reconsiderado públicamente su creencia previa de que es imposible ser razonable y ser creyente:

“La afirmación de que una persona razonable no puede creer en Dios puede ser cuestionada seriamente… Personalmente, he conocido a muchos creyentes que llamaría personas muy racionales, razonables e inteligentes. No los llamaría simplemente racionales, razonables e inteligentes en general, sino que continuaría diciendo que son racionales, razonables e inteligentes con respecto a su creencia en Dios”[33].

Mera afirmación

“Simplemente afirmar algo, no importa cuán fuerte sea, no lo hace cierto. La afirmación confiada no puede sustituir al argumento…” – Nigel Warburton[34].

Una de las principales fallas de Against All Gods (Contra todos los dioses) es la indulgencia repetida de Grayling en la afirmación falsa, o al menos infundada, afirmación. Por ejemplo, Grayling simplemente afirma que “la religión es un dispositivo hecho por el hombre, no menos importante es la opresión y el control”[35]. No hay evidencia o argumentos en apoyo de esta amplia generalización. Por otra parte, Grayling afirma que la historia del nacimiento de Jesús está a la par de otros cuentos de Medio Oriente, como “Hércules y sus labores”[36]. No hay ningún compromiso con los estudios históricos relevantes aquí. Además, no hay compromiso con las muchas obvias dis-analogías entre el testimonio histórico acerca de Jesús por un lado[37], y la mitológica historia genérica de Grayling de una deidad que embaraza a una mujer mortal que luego da a luz a una figura heroica cuyas obras le dan lugar en el cielo[38] en el otro. Por ejemplo, el Nuevo Testamento no presenta a Jesús como que se ganó su lugar en el cielo por sus obras. En todo caso, él se presenta como “ganándose” nuestro lugar en el cielo. Cuentos de dioses embarazando a mujeres mortales de semidioses heroicos (y Jesús no es semi dios en los evangelios) puede haber sido común en el Medio Oriente, pero no eran en absoluto comunes en el contexto judío que dio origen al cristianismo. El ataque de Grayling a la creencia en la concepción virginal de María es pura fanfarronería:

“pregúntale a un cristiano por qué la historia antigua de una deidad que embaraza a una mujer mortal… es falsa tal como se aplica a Zeus y sus muchos amantes… pero verdadera como se aplica a Dios, María y Jesús… No esperes una respuesta racional; un llamamiento a la fe será suficiente, porque con la fe todo vale”[39].

Desafortunadamente para Grayling, esta amplia generalización es demostrablemente falsa. Por ejemplo, mientras era profesor de Historia y Filosofía de la Religión en el King’s College de la Universidad de Londres, el filósofo cristiano Keith Ward escribió un artículo sobre “Evidencia del nacimiento virginal” en el que justificaba la creencia en la historia de la Natividad con evidencia:

“El argumento más fuerte para la veracidad de estos relatos es que es muy difícil ver por qué deberían haber sido inventados, cuando hubieran sido tan impactantes para los oídos judíos… hay dos fuentes independientes de historias de un nacimiento de virgen; y eso aumenta la probabilidad de que se fundan en recuerdos históricos”[40].

Independientemente de si los argumentos históricos de Ward son sólidos (creo que lo son), el punto es que Grayling está claramente equivocado sobre la creencia cristiana en el nacimiento virginal que no tiene nada que ver con la evidencia. Algunos cristianos pueden creer en el nacimiento virginal sin evidencia directa (algunos incluso podrían creer sin evidencia indirecta). Pero algunos cristianos al menos sostienen esta creencia porque creen que la evidencia merece directamente que lo hagan.

Por supuesto, Grayling descarta la idea de que “es razonable que la gente crea que los dioses suspenden ocasionalmente las leyes de la naturaleza”[41]. Si el plural se reemplaza con el singular, esta es una creencia que tengo y que creo que es razonable. Grayling no me ofrece ninguna razón para pensar que estoy equivocado; él simplemente (indirectamente) afirma que lo estoy. Del mismo modo, en The Meaning of Things (El significado de las cosas) Grayling afirma irónicamente que: “La feliz realidad de los milagros es que no requieren apoyo en el camino de la evidencia o la evaluación racional0”[42]. Como generalización, esta afirmación es simplemente falsa. Tanto Jesús como los escritores del Nuevo Testamento apelaron a los milagros de Jesús como evidencia de la verdad de sus afirmaciones personales precisamente porque hubo testimonio de testigos oculares de su aparición. Desde entonces hasta el presente los apologistas cristianos han presentado argumentos basados en evidencia para reclamos milagrosos, especialmente por el milagro de que Jesús resucitó de entre los muertos. Si estos argumentos son o no sólidos, no viene al caso que nos ocupa. El mero hecho de que los argumentos son ofrecidos es suficiente para hundir la afirmación de Grayling. Filosóficamente hablando, me parece que si la creencia en Dios es razonable, entonces la creencia en los milagros es razonable, al menos en principio. Como argumentó Ward en su artículo sobre el nacimiento virginal:

“Si hay un Dios… todas las leyes de la física y la química, etc., deben ser mantenidas por Él. Bien podemos esperar que Él continúe permitiendo que tales leyes operen; de lo contrario, nunca sabríamos qué sucedería a continuación. Pero no hay ninguna razón para que Él algunas veces no haga cosas que no sean predecibles solo con las leyes de la física o la biología. Dios puede hacer lo que quiera con su propio universo”[43].

Dado que me parece que la creencia en Dios es razonable, me parece que la creencia en los milagros es (en principio) razonable. Una de las razones por las que me parece que creer en Dios es razonable es que ofrece la mejor explicación para la existencia del mundo natural. De hecho, Grayling sugiere que quizás las personas religiosas:

“necesitan creer en agentes [sobrenaturales] porque de otra manera no pueden entender cómo puede haber un mundo natural, como invocando al “Caos y la noche anterior” (en una mitología del Medio Oriente, los progenitores de todas las cosas) explicaran cualquier cosa, y mucho menos la existencia del universo. Hacerlo podría satisfacer una necesidad metafísica patológica de lo que Paul Davies llama “la super-tortuga auto-levitante”, pero obviamente no vale la pena discutirlo”[44].

Admito que no puedo, además de una creencia en algún tipo de dios, entender cómo puede haber un mundo natural. Sin embargo, no admito que esto se deba a una peculiar falla de imaginación de mi parte. Los comentarios de Grayling exhiben un rechazo francamente sorprendente de abordar las complejas cuestiones filosóficas que rodean a varias versiones del argumento cosmológico defendido por destacados filósofos contemporáneos de la religión (por ejemplo, W. David Beck, William Lane Craig, Alexander R. Pruss, Robert C. Koons, la lista continúa); una evasión que sustituye el psicoanálisis de sillón y las referencias de paja a la mitología por el diálogo racional. La pregunta es si nadie (no solo las “personas religiosas”) pueden entender cómo puede haber un mundo natural sin una causa sobrenatural. Argumentos cosmológicos, como su nombre indica, discutir que no pueden, porque la comprensión más plausible de la existencia del mundo natural es, de hecho, que hay más en la realidad que en el mundo natural. Contra estos argumentos, Grayling dirige un esnobismo cronológico poco sofisticado (que C.S. Lewis definió como: “La aceptación acrítica del clima intelectual de nuestra propia época y la suposición de que lo que haya quedado desactualizado es por ese lado desacreditado”[45]) y una insinuación indirecta de que todos los teístas sufren de algún tipo de bloqueo mental que les impide compartir la visión superior del naturalista sobre los por qué y los por qué de la realidad. ¿Cuál es la comprensión que ofrece Grayling de cómo puede haber un mundo natural? Ninguna. Simplemente afirma que el naturalismo es verdadero: “Ningún ateo debe llamarse a sí mismo uno… Un término más apropiado es ‘naturalista’, que denota que el universo es un reino natural, gobernado por las leyes de la naturaleza. Esto correctamente implica que no hay nada sobrenatural en el universo…”[46]. Ciertamente implica esta conclusión; no la justifica. Grayling escribe que: “Las personas con creencias teístas deberían llamarse sobrenaturales, y se les puede permitir intentar refutar los hallazgos de la física, la química y las ciencias biológicas en un esfuerzo por justificar su afirmación alternativa de que el universo fue creado, y es dirigido por seres sobrenaturales”[47]. Sin embargo, esto equivale a otra aseveración porque, en el mejor de los casos, Grayling simplemente está asumiendo que el teísmo soporta una carga de prueba que el ateo no posee.

Fue otro filósofo británico, Antony Flew (que recientemente se convirtió en teísta[48]), quien más famoso instó a que la “carga de la prueba recae sobre el teísta”[49], y que a menos que se puedan dar razones convincentes para la existencia de Dios, debería haber una “presunción de ateísmo”. Sin embargo, por ‘ateísmo’, Flew quería decir simplemente ‘no-teísmo’, una definición no estándar de ‘ateísmo’ que incluye el agnosticismo, pero excluye el ateísmo como comúnmente se entiende. La presunción de ateísmo, por lo tanto, no es particularmente interesante a menos que (como parece ser la suposición de Grayling) realmente sea la presunción de ateísmo en lugar de la presunción de agnosticismo. Sin embargo, el primero es mucho más difícil de defender que el segundo:

“la ‘presunción del ateísmo’ demuestra una manipulación de las reglas del debate filosófico para jugar en manos del ateo, quien hace una afirmación de la verdad. Alvin Plantinga correctamente argumenta que el ateo no trata con las afirmaciones de ‘Dios existe’ y ‘Dios no existe’ de la misma manera. El ateo asume que si uno no tiene evidencia de la existencia de Dios, entonces uno está obligado a creer que Dios no existe, ya sea que tenga evidencia o no en contra de la existencia de Dios. Lo que el ateo no puede ver es que el ateísmo es tanto una afirmación de saber algo (“Dios no existe”) como el teísmo (“Dios existe”). Por lo tanto, la negación de la existencia de Dios por parte del ateo necesita tanta justificación como lo hace la afirmación del teísta; el ateo debe dar razones plausibles para rechazar la existencia de Dios… en ausencia de evidencia de la existencia de Dios, el agnosticismo, no el ateísmo, es la presunción lógica. Incluso si los argumentos a favor de la existencia de Dios no persuaden, no se debe presumir el ateísmo porque el ateísmo no es neutral; el agnosticismo puro sí lo es. El ateísmo se justifica solo si hay suficiente evidencia contra la existencia de Dios”[50].

Como escribe Scott Shalkowski: “Basta decir que si no hubiera ninguna evidencia para creer en Dios, esto [en el mejor de los casos] legitimaría meramente el agnosticismo a menos que exista evidencia contra la existencia de Dios”[51].

Por otra parte, ¿por qué el teísta necesitaría refutar cualquiera de los hallazgos de la ciencia moderna? Por un lado, Grayling realmente no dice lo que él considera que son los hallazgos de la ciencia moderna; por otro lado, él no explica por qué él piensa que esos supuestos hallazgos están en tensión con cualquier creencia religiosa en particular. Explica que no considera la teoría del Diseño Inteligente como uno de los hallazgos de la ciencia moderna (como algunos, incluso yo mismo); pero la definición de identidad de Grayling es un hombre de paja (lo confunde con el creacionismo)[52] e incorrectamente lo etiqueta un argumento de la ignorancia[53]), y su compromiso con el argumento de Michael Behe a partir de la complejidad irreductible biomolecular es leve, por decir lo menos[54].

Grayling escribe que: “En contraste con las certezas absolutas de la fe, un humanista tiene una concepción más humilde de la naturaleza y la extensión actual del conocimiento. Todas las preguntas que la inteligencia humana realiza para ampliar el conocimiento progresa siempre a expensas de generar nuevas preguntas”[55]. Me identifico con el enfoque ‘humilde’ de Grayling al conocimiento; pero me pregunto si Grayling está incluso abierto a la posibilidad de que algunas de esas preguntas generadas por el progreso del conocimiento (especialmente el conocimiento científico) puedan tener a ‘Dios’ como su verdadera respuesta. Si Grayling no está abierto a esta posibilidad, sus protestas de humildad epistemológica son propensas a sonar falsas. Si él está abierto a esta posibilidad, entonces uno se pregunta ¿qué hacer con sus afirmaciones sobre la supuesta “lenta, pero sangrienta retirada de la religión”[56] frente al progreso científico? En el mejor de los casos, estas afirmaciones tendrían que indicar una inferencia tentativa y que pueda refutarse a partir de la evidencia disponible en lugar de una suposición dogmática de que la ciencia y la religión están necesariamente en desacuerdo con la religión del lado perdedor.

De hecho, la descripción de Grayling de la “lenta, pero sangrienta retirada de la religión”[57] es un anacronismo académico. Como Alister McGrath reporta: “La idea de que la ciencia y la religión están en perpetuo conflicto ya no es tomada en serio por ningún gran historiador de la ciencia”[58]. De hecho, según el ateo Michael Ruse:

“La mayoría de la gente piensa que la ciencia y la religión están, y necesariamente deben estarlo, en conflicto. De hecho, esta metáfora de la “guerra”, tan amada por los racionalistas del siglo XIX, tiene solo una aplicación tenue a la realidad. Durante la mayor parte de la historia del cristianismo, fue la Iglesia el hogar de la ciencia… No fue hasta el siglo XVII, en el momento de la Contrarreforma, que la Iglesia Católica mostró verdadera hostilidad hacia la ciencia, cuando condenó a Galileo por su promulgación del heliocentrismo copernicano. (Copérnico mismo no había sido simplemente un buen católico, fue un sacerdote). En el siglo XIX, la Iglesia Católica había vuelto a su papel tradicional… es cierto que la llegada de la evolución, particularmente en la forma de Origen de las especies de Charles Darwin, pone esta tolerancia a severa prueba. Pero sin negar que había opiniones fuertes en ambos lados, la verdad parece ser que gran parte de la supuesta controversia era una función de la imaginación de los no creyentes (especialmente Thomas Henry Huxley y sus amigos), quienes estaban decididos a matar dragones teológicos existieran o no”[59].

Grayling señala que “los supernaturalistas gustan de afirmar que algunas personas irreligiosas recurren a la oración cuando están en peligro de muerte, pero los naturalistas pueden responder que los sobrenaturalistas generalmente depositan gran fe en la ciencia cuando se encuentran (digamos) en un hospital o un avión, y con mucha mayor frecuencia”[60]. En otras palabras, los naturalistas pueden ser inconsistentes, pero los teístas son más inconsistentes. Desafortunadamente para Grayling, el naturalista que ora in extremis y el sobrenaturalista que confía en la ciencia en su día a día simplemente no son análogos. El naturalista que ora es alguien cuya acción es coherente con las creencias que están en contradicción con sus creencias cotidianas. El supernaturalista que va al hospital no ve ninguna incoherencia entre confiar en un cirujano y confiar en Dios, y ¿por qué deberían hacerlo? Grayling admite que: “Los supernaturalistas pueden afirmar que la ciencia misma es un regalo de Dios, y así justificarlo”[61]. Como escribe Alvin Plantinga: “La ciencia moderna surgió dentro del seno del teísmo cristiano; es un brillante ejemplo de los poderes de la razón con los que Dios nos creó; es una exhibición espectacular de la imagen de Dios en nosotros los seres humanos. Así que los cristianos se comprometen a tomar la ciencia y las liberaciones de la ciencia contemporánea con la mayor seriedad”[62]. Sin embargo, Grayling quiere recordar a los creyentes que Karl Popper dijo que “una teoría que explica todo no explica nada”[63]. Se supone que esta observación revela la locura de la posición supernaturalista. Grayling aparentemente (es imposible estar seguro) tiene algo así como el siguiente argumento en mente:

- Un supernaturalista que confía en cualquier cosa (o tal vez en todo) que la ciencia nos dice está contradiciendo su cosmovisión o no.

- Si están contradiciendo su cosmovisión, su cosmovisión no puede mantenerse de manera consistente y debe ser archivada.

- Si no contradicen su cosmovisión, esto solo puede ser porque su cosmovisión es compatible con lo que sea o puedan ser los hallazgos de la ciencia.

- Pero una cosmovisión que sea compatible con lo que los hallazgos de la ciencia son o podrían ser explicaciones de todo y, por lo tanto, no explica nada.

- Una cosmovisión que no explica nada debe ser archivada.

- Por lo tanto, de cualquier manera, el sobrenaturalismo debe ser archivado.

Hay varios problemas con este argumento. En primer lugar, ¿si una persona no puede vivir su cosmovisión consistentemente en ocasiones, esto necesariamente significa que su cosmovisión debe ser archivada (o que es falsa)? ¿Debería un ateo dejar de lado su ateísmo en el momento en que se encuentra orando? Las cosmovisiones constantemente incompatibles son sospechosas, pero la falta de incompatibilidad es una cuestión de condición y, en el mejor de los casos, solo está relacionada indirectamente con la racionalidad o la verdad de una cosmovisión. En segundo lugar, si un supernaturalista no es inconsistente al visitar un hospital, no está contradiciendo nada de lo que cree que la ciencia realmente tiene que decir sobre el mundo; pero esto no significa que su cosmovisión sea necesariamente consistente con nada que la ciencia podría decir con sinceridad sobre la realidad. Las creencias religiosas pueden incluir, y de hecho implican, afirmaciones de la verdad que tienen el potencial de entrar en conflicto con el conocimiento científico. Por ejemplo, la afirmación de la verdad de que Jesús resucitó entraría en conflicto con la ciencia si los arqueólogos alguna vez hubieran descubierto los huesos de Jesús. Hubo incluso un reclamo reciente, aunque académicamente ridiculizado y muy desacreditado, en este sentido[64]. Finalmente, Grayling aplica comentarios de Poppers fuera de contexto, siendo el contexto de teorización científica. Las teorías metafísicas no pueden simplemente suponerse que estén sujetas a los mismos criterios que las teorías científicas. De hecho, la observación de Popper debe ser entendida dentro del contexto de su filosofía falsacionista de la ciencia, una filosofía ahora ampliamente abandonada por los filósofos de la ciencia. Por lo tanto, incluso haciendo nuestro mejor esfuerzo para construir el tipo de argumento que Grayling parece estar formulando cuando cita a Popper, no encontramos nada de alguna sustancia. Por supuesto, Grayling podría ser capaz de construir un argumento más sustancial para llenar su nombre Popperiano; pero el hecho de que nos vemos obligados a hacer el trabajo por él, revela cuán dependiente de la afirmación es su polémica.

Religión y la esfera pública

“La tolerancia es una virtud rara e importante. Tiene sus límites, pero por lo general están demasiado apretados y en lugares equivocados”. – A.C. Grayling[65]

Grayling escribe: “Es hora de revertir la noción predominante de que el compromiso religioso es intrínsecamente merecedor de respeto, y que debe manejarse con guantes y protegido por la costumbre y en algunos casos la ley contra la crítica y el ridículo”[66]. Estoy de acuerdo en que no es un compromiso religioso per se lo que merece respeto; sino la persona con un compromiso religioso que merece respeto y cuyo compromiso (en igualdad de condiciones) debe ser respetado, es decir, al menos tolerado en una sociedad libre. Como Grayling escribe: “Lo que hay que hacer en oposición a la respuesta predecible de los creyentes religiosos es que los individuos humanos merecen respeto ante todo como individuos humanos“[67]. El cristianismo está de acuerdo con Grayling en este punto; no hay ninguna base en la teología cristiana para valorar a una persona más que a otra, ciertamente no sobre la base de lo que creen:

“La humanidad compartida 2025 es la base última de todas las relaciones persona a persona y de grupo a grupo, y puntos de vista que establecen diferencias entre los seres humanos como base de consideración moral, especialmente aquellas que implican reclamos de posesión por parte de un grupo de mayor verdad, santidad o similares, comienzan en el lugar absolutamente equivocado”[68].

Como cristiano, digo ‘Amén’. El punto de Grayling puede haber atacado algunas religiones, pero está fundamental en acuerdo con el cristianismo. De hecho, la posición de Grayling es una expresión del humanismo que deriva de las raíces cristianas del humanismo en el Renacimiento (y, por último, por supuesto, dentro de la Biblia), con eruditos como el humanista y teólogo holandés Desiderio Erasmo. Grayling escribe:

“Es hora de exigir a los creyentes que tomen sus elecciones personales y preferencias en estos asuntos no racionales y con demasiada frecuencia peligrosos en la esfera privada, como sus inclinaciones sexuales. Todos son libres de creer lo que quieran, siempre que no molesten (o coaccionen o maten) a otros… es hora de exigir y aplicar un derecho para el resto de nosotros a la no interferencia de personas y organizaciones religiosas: un derecho a ser libres de proselitismo y los esfuerzos de los grupos minoritarios autoseleccionados para imponer su propia elección de moralidad y práctica a quienes no compartimos su punto de vista”[69].

Ciertamente puedo estar de acuerdo con Grayling en que nuestro sistema democrático podría construirse mejor hasta el fin de representar los puntos de vista de la población y decidir los asuntos sobre la base de argumentos relevantes. Sin embargo, sí vivimos en una democracia, y apenas no se trata de minorías religiosas imponiendo su propia elección de moralidad y práctica a aquellos que no comparten su punto de vista. (De hecho, el caso es a menudo todo lo contrario, como lo demuestra el reciente debate sobre las agencias de adopción católicas[70]) Grayling puede muy bien quejarse acerca de: “Personas de fe religiosa, que se dan el derecho incuestionable de respetar la fe a la que se adhieren, y un derecho a avanzar, si no es que imponer (porque dicen saber la verdad, recuerden) sus opiniones sobre los demás”[71]. Sin embargo, como cristiano, no es tanto mi fe que creo que tiene derecho a ser respetada, ya que mi persona como ser humano tiene derecho al respeto. Este no es un derecho que excluya la disidencia o el cuestionamiento intelectual robusto de los no creyentes. Tampoco excluye la polémica artística de comediantes, dibujantes, guionistas y otros. Sin embargo, se extiende al derecho a esperar que los detractores no participen en ataques ad hominem, o para atacar con caricaturas de hombres de paja de mi posición. De hecho, este derecho no es más que la expectativa de que aquellos que quieran criticar mis creencias deberían estar sujetos a los mismos estándares del discurso académico civil que deberían aplicarse cuando la bota es, por así decirlo, del otro pie.

Por otra parte, Grayling claramente se toma a sí mismo para tener derecho a presentar (e incluso, como veremos más adelante, para imponer) sus puntos de vista sobre los demás, precisamente porque afirma conocer la verdad (al menos conocer la verdad mejor que cualquier creyente religioso la conoce). Quejándose de los creyentes religiosos que se dedican precisamente al mismo tipo de actividad, precisamente por la misma razón, enloda a Grayling en un doble estándar (este fango depende de cuánto más uno lee de la polémica de Grayling). Irónicamente (y dejando de lado la afirmación de Grayling de que todas las creencias religiosas son preferencias no racionales), en su defensa de la creencia de que “todos son libres de creer lo que quieren, siempre que no molesten (o coaccionen o maten) a otros…”[72], Grayling está: a) molestando a las personas religiosas al escribir una polémica en contra de sus creencias (algo que estoy feliz de que él haga), y b) abogar por la coacción a creyentes religiosos. Su posición parece ser que las personas deberían ser libres de tener las creencias religiosas que deseen sin temor a la coacción, etc., siempre y cuando no crean que sus creencias deberían acompañarlos a la esfera pública, en cuyo caso deberían ser obligados a no hacerlo. Dado que las creencias de Grayling implican la coacción de los demás, de acuerdo con sus propios criterios ¡él no debería ser libre de creer como lo hace! Grayling claramente ha dibujado los límites de la tolerancia demasiados estrechos, y por lo tanto ha caído dentro de su propia definición de intolerancia: “Una persona intolerante… desea que otros vivan como él cree que deberían y… busca imponer sus prácticas y creencias sobre ellos”[73]. La sugerencia de Grayling va más allá de su afirmación anterior, en The Meaning of Things (El significado de las cosas), que: “La única coacción debería ser la del argumento…”[74].

Si Grayling quiere creer que se debe obligar a las personas a no llevar sus creencias religiosas a la esfera pública, debe aceptar que las personas son libres de creer que las personas deben ser libres de llevar sus creencias religiosas a la esfera pública. Grayling no puede tener las dos cosas sin caer en un doble estándar autocontradictorio, autoexceptor. De hecho, Grayling adopta otra regla de autoexcepción cuando aboga por “el derecho a ser libre de proselitismo”, ¿qué es Against All Gods (Contra todos los dioses), sino un acto de proselitismo para el humanismo secular? Sin duda, todos deberían tener el derecho de invitar al debate público sobre su propia cosmovisión; e igualmente todos deben tener el derecho de no leer, escuchar, mirar o participar en una conversación sobre estos temas cuando se ofrece. Por ejemplo, tanto los Testigos de Jehová como los Humanistas Seculares deberían, creo, tener el derecho de llamar a mi puerta ofreciéndome literatura y discusión (no es que esto último lo haga). Y debería tener el derecho de invitarlos a una charla, o de despedirlos amablemente, como mejor me parezca. Grayling no dice nada sobre los derechos de los religiosos a no ser proselitistas por parte de los no religiosos (por lo tanto, sus derechos propuestos discriminan a los religiosos). Permítanme ser claro, no quiero ningún derecho semejante: quiero que los humanistas seculares sean libres de escribir libros públicos como Against All Gods (Contra todos los dioses); sino a cambio parece justo esperar el derecho de respuesta pública.

Grayling afirma la necesidad de “devolver el compromiso religioso a la esfera privada…”[75]. Desafortunadamente, hay al menos algunas formas de creencias religiosas que son esencialmente de mentalidad pública. Por ejemplo, el cristianismo es, por su propia naturaleza, una religión misionera y una religión que toma en serio servir a otros. Tales creencias simplemente no pueden ser relegadas a la esfera privada mientras se mantienen. Uno no puede simplemente prohibir la proclamación pública del mensaje del ‘evangelio’, o actos públicos de caridad cristiana, sin por ello prohibir efectivamente el cristianismo mismo. Si Grayling está realmente comprometido a excluir a toda religión de la esfera pública, exigiendo y aplicando un derecho de los no religiosos a la “no interferencia”, por lo tanto, está necesariamente comprometido con la prohibición del cristianismo.

[Anexo: En una reciente conversación de radio con Grayling, me complació encontrarlo en un estado de ánimo más liberal, pero me sorprendió descubrir que pensaba que “proselitismo ” era sinónimo de “lavado de cerebro”, que ciertamente ¡no es la definición de diccionario del término! cf. A.C. Grayling y Peter S. Williams, ‘The God Argument’ (El argumento de Dios) http://www.bethinking.org/who-are-you-god/advanced/unbelievable-ac-graylings-the-god-argument.htm / http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/spanish/proselytize]

No me gusta el corte de tu pluma

Grayling ofrece un psicoanálisis sin pruebas de creyentes religiosos que: “Entran en el dominio público vistiendo o luciendo declaraciones visuales inmediatamente obvias de su afiliación religiosa…”[76]. De acuerdo con Grayling:

“Al menos uno de sus motivos para hacerlo es que se le otorgue la identidad primordial de un devoto de esa religión, con la demanda implícita asociada de que, por lo tanto, se le dé algún tipo de tratamiento especial, incluido el respeto… aunque excentricidades de la vestimenta y la creencia fueron de poca importancia en nuestra sociedad, cuando el compromiso religioso personal estaba más reservado a la esfera privada, a la que pertenece correctamente, de lo que lo ha hecho últimamente su politización”[77].

Sin embargo, no es difícil imaginar otros motivos además del único atributo de Grayling, y uno se pregunta si Grayling diría lo mismo acerca de usar los colores del equipo de fútbol de su país o nación .Si usar una declaración visual inmediatamente obvia de la asociación religiosa de uno es un acto político, ¿se debe desaprobar solo sobre ese hecho? En ese caso, ¿no sería igualmente sospechoso el uso de un traje de baño de la bandera del Reino Unido en la playa, especialmente en el extranjero? Y si la última sugerencia es una reducción absurdum de la primera, ¿la naturaleza sospechosa del acto político en cuestión es solo un asunto de su contenido religioso? ¿En qué caso Grayling está defendiendo que repudiemos cualquier y toda expresión religiosa, por menor que sea? ¿O es el supuesto problema aquí una cuestión de condición? Porque hay una diferencia obvia entre llevar una cruz pequeña en una cadena por un lado y por el otro llevar una cruz de tamaño completo por las calles en Semana Santa. ¿Grayling quiere imponer una prohibición contra ambas formas de expresión, o solo la última? Grayling es bastante vago acerca de cuán iliberal es él aquí.

Sin embargo, la actitud abiertamente antiliberal de Grayling a la religión raya en la paranoia. Afirma que: “Cuando cualquiera de estas ideologías encarceladas está a la zaga y/o en minoría, presentan rostros dulces a aquellos que desean seducir: el beso de la amistad en la iglesia parroquial, el campamento de verano para jóvenes comunistas en la década de 1930. Pero dales las palancas del poder y son los talibanes, la Inquisición, la Stasi[78]. No es de extrañar que Grayling piense que debemos ser duros con la religión y duros con las causas de la religión. ¡Aparentemente, un enfoque de tolerancia cero es la única forma de salvar la civilización occidental de una Inquisición de la Iglesia de Inglaterra! El comediante Eddie Izzard una vez realizó un acto hilarante que involucró tal inquisición, presentando el ‘Torta o muerte a la Iglesia de Inglaterra’, en la que las autoridades religiosas obligaron a la gente a elegir entre un buen trozo de torta o la muerte. En otras palabras, es difícil tomar en serio la paranoia radical de Grayling. Frente a esto, Grayling sin duda respondería que: “En su forma moderna, moderada y paliativa, el cristianismo es una versión reciente y altamente modificada de lo que, durante la mayor parte de su historia, ha sido una ideología a menudo violenta y siempre opresiva… un monje medieval quien se despertó hoy… no podría reconocer la fe que lleva el mismo nombre que la suya”[79]. Si bien es una lástima que no tengamos monjes medievales a quienes plantear esta pregunta, podría considerarse ser algo así como una pista falsa. Tal vez antes de la reforma (y contrarreforma) el cristianismo medieval era aberrante para los estándares del cristianismo auténtico del Nuevo Testamento, que es, después de todo, el único estándar que realmente cuenta. Pero si Grayling tiene razón acerca de que el cristianismo contemporáneo tiene al menos una forma que es una aberración en su naturaleza modesta y permisiva, entonces está equivocado sobre que toda religión esté a la par con la Stasi. Grayling no puede tener las dos cosas.

¿Puede un ateo ser un fundamentalista?

Grayling piensa que no, pero yo quiero diferir. Grayling está molesto por:

“Los apologistas religiosos [que] acusan a los no religiosos de ser ‘fundamentalistas’ si atacan la religión con demasiada solidez, sin parecer darse cuenta de la ironía de emplear, como término de abuso, una palabra que se aplica principalmente a las tendencias demasiado comunes de su propia perspectiva. ¿Puede un punto de vista que no es una creencia sino un rechazo de cierto tipo de creencia ser realmente ‘fundamentalista’? Por supuesto no…”[80]

Sin embargo, el mismo Grayling señala que no ser religioso, o más específicamente ser un ‘ateo’, es en el mejor de los casos una descripción parcial de una cosmovisión no religiosa más amplia: “Como sucede, ningún ateo debería llamarse a sí mismo uno… el término más apropiado es “naturalista”, que denota quien toma que el universo es un reino natural…”[81]. En el uso popular ‘ateo’ se utiliza como sinónimo de ‘naturalista metafísico’, y mientras estrictamente hablando de ateísmo puede o no puede ser incapaz de la calificación fundamentalista, naturalismo metafísico (‘ateísmo’ en su sentido popular) es sin duda capaz de la hazaña, como lo demuestra ampliamente la existencia de Richard Dawkins. Grayling busca evitar la etiqueta fundamentalista aplicada a su propia posición jugando con un equívoco sobre el significado del “ateísmo”.

Grayling afirma: “Es también el momento de dejar de lado… una frase utilizada por algunas personas religiosas cuando se habla de quienes hablan abiertamente sobre su incredulidad en cualquier afirmación religiosa: la frase “ateo fundamentalista”[82]. El mero hecho de que ‘fundamentalista’ se utiliza para calificar ‘ateo’ en esta frase debería llevar a Grayling al hecho de que no tiene la intención de describir a aquellos que son simplemente “francos sobre su incredulidad a cualquier afirmación religiosa”. Sin embargo, Grayling parece pensar que “fundamentalista” es necesariamente un calificador redundante cuando se lo vincula con el ateísmo, y plantea la siguiente pregunta retórica: “¿Qué sería un ateo no fundamentalista? ¿Sería él alguien que solo creyera un tanto que no existen entidades sobrenaturales en el universo…?[83] Si bien el concepto de ateo con dudas es aparentemente incomprensible para Grayling, parece tener tanto sentido como un ‘cristiano de domingos’ para mí. Sin embargo, sugiero que una mejor respuesta a la pregunta de Grayling es que el ‘ateo fundamentalista’ significa un ateo que piensa que la creencia en Dios es una falla intelectual y ética perniciosa a la que deben oponerse activamente los no creyentes de buen juicio. En otras palabras, un ateo fundamentalista es lo que apodó un miembro del movimiento de la Revista Wired como “El nuevo ateísmo” en una historia de portada de noviembre de 2006 por el editor y agnóstico Gary Wolf:

‘Los nuevos ateos no nos dejarán salir del anzuelo simplemente porque no somos creyentes doctrinarios. Condenan no solo la creencia en Dios sino el respeto por creer en Dios. La religión no solo es incorrecta; es malvada. Ahora que la batalla se ha unido, no hay excusa para eludir. Tres escritores han llamado este llamado a las armas. Ellos son Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris y Daniel Dennett[84].

El Against All Gods (Contra todos los dioses) de Grayling es claramente otra reserva del campo ‘Nuevo (o ‘fundamentalista’) ateo’.

En 2006 el darwinista Michael Ruse tuvo un intercambio de correos electrónicos notoriamente malhumorado con Daniel Dennett en el que el primero etiquetó el libro de este último Breaking the Spell (Rompiendo el hechizo) “realmente malo y no digno de ti”[85]:

“Creo que tú y Richard [Dawkins] son absolutos desastres en la lucha contra el diseño inteligente: estamos perdiendo esta batalla… lo que necesitamos no es un ateísmo rotundo sino una lucha seria con los problemas, ninguno de ustedes está dispuesto a estudiar el cristianismo en serio y comprometerse con las ideas, es simplemente tonto y grotescamente inmoral afirmar que el cristianismo es simplemente una fuerza para el mal, como afirma Richard: más que eso, estamos en una pelea, y tenemos que hacer aliados en la lucha , no simplemente alienar a todos de buena voluntad”[86].

Sorprendentemente, Ruse aprovechó la oportunidad para criticar a Dawkins en la portada de la respuesta conjunta de Alister y Joanna McGrath a El espejismo de Dios (titulada El espejismo de Dawkins), donde Ruse afirmó:

“El espejismo de Dios me avergüenza de ser ateo, y los McGrath muestran por qué”.

Ruse continuó su debate sobre las tácticas con los ateos fundamentalistas en un artículo para Skeptical Inquirer que lamentaba el estado fracturado del ateísmo frente al “creacionismo” (que para Ruse es un término que abarca la teoría del Diseño Inteligente):

“en este momento, aquellos de nosotros contra el creacionismo vivimos en una casa dividida. Un grupo está formado por los ardientes, completos ateos. No quieren tener nada que ver con el enemigo, que están dispuestos a definir como cualquier persona de inclinación religiosa, desde literalistas (como un Bautista del Sur) a deístas (como unitario), y piensan que cualquiera que piense lo contrario es tonto, equivocado, e inmoral. Miembros destacados de este grupo incluyen a Richard Dawkins… Daniel Dennett… y Jerry Coyne… El segundo grupo… contiene a aquellos que no tienen creencias religiosas, pero que piensan que uno debería colaborar con cristianos liberales [por medio de los cuales Ruse quiere decir evolucionistas teístas] contra un enemigo compartido, y que se inclinan a pensar que la ciencia y la religión son compatibles”[87].

Ruse reconoció que en este debate interno:

“La retórica es fuerte y desagradable. He acusado a Dennett de ser un matón y alguien que es un cerdo ignorante de los problemas. Me ha dicho que estoy en peligro (quizás por encima del peligro) de perder el respeto de aquellos cuyo respeto debería desear… Dawkins ha ido más allá; en su nuevo libro más vendido, El espejismo de Dios, Dawkins me compara con Neville Chamberlin, el primer ministro británico que trató de apaciguar a Adolf Hitler[88].

Ruse respondió pragmáticamente a Dawkins que: “Cuando Hitler [es decir, el “creacionismo”] atacó a Rusia [es decir, la evolución teísta], Inglaterra y Estados Unidos dieron ayuda a Stalin [es decir, a los cristianos “liberales”]. No es que les gustara especialmente Stalin, pero trabajaron según el principio de que el enemigo de mi enemigo es mi amigo[89]. Ruse terminó su artículo con un llamado a la unidad: “Fundamentalismo, creacionismo, teoría inteligente del diseño: estas son las amenazas reales. Agradar a Dios –o a ningún Dios– dejemos de luchar contra nosotros mismos y sigamos con el trabajo real que enfrentamos”[90]. Sin embargo, parece poco probable que esta petición esté dirigida por personas como el Profesor Grayling, porque Ruse señala: “La escuela Dawkins-Dennett no permite ningún compromiso. La religión es falsa. La religión es peligrosa. La religión debe combatirse en todos los sentidos. No puede haber trabajo con el enemigo [incluso los evolucionistas teístas “liberales”]. Los que como yo trabajamos con personas religiosas somos como los apaciguadores ante los nazis”[91]. Por lo tanto, una respuesta a la pregunta retórica de Grayling sobre lo que sería un ateo no fundamentalista es que serían como Michael Ruse.

“Podría ser”, le pregunta Grayling con la lengua firmemente en la mejilla, “que un ateo no fundamentalista es alguien a quien no le importa que otras personas tengan creencias profundamente falsas y primitivas sobre el universo, sobre cuya base [alerta de generalización generalizada] han pasado siglos asesinando en masa a otras personas que no tienen exactamente las mismas creencias falsas y primitivas que ellos mismos, ¿y todavía lo hacen?[92] Por supuesto que no; pero luego Grayling plantea un falso dilema. No es que los ateos como Michael Ruse no tenga en cuenta que otras personas tienen lo que consideran creencias falsas; es solo que preferirían involucrar a los creyentes en un debate inteligente y respetuoso siempre que sea posible, en lugar de emitir el equivalente ateo de una fatwa islámica a cualquiera con la temeridad de estar en desacuerdo con ellos. (Estoy tentado a escribir “en desacuerdo con sus creencias primitivas” para hacer una observación sobre el esnobismo cronológico de Grayling[93]; después de todo, el naturalismo se remonta a los filósofos presocráticos de la antigua Grecia).

¿Puede el humanismo ser religioso?

Según Grayling: “El humanismo en el sentido moderno del término es la opinión de que cualquiera que sea su sistema ético, se deriva de su mejor comprensión de la naturaleza humana y la condición humana en el mundo real”[94]. Me parece que un cristiano podría hacer esta afirmación humanista. Sin embargo, Grayling afirma que la ética humanística ‘significa que no, en su pensamiento sobre el bien y sobre nuestras responsabilidades con nosotros mismos y entre nosotros, establece datos putativos de astrología, cuentos de hadas, creencias sobrenaturalistas, animismo, politeísmo o cualquier otra herencia de las edades del pasado remoto y más ignorante de la humanidad”. Aparte de otro ejemplo evidente de esnobismo cronológico, Grayling no hace nada para justificar su afirmación sobre este punto. Por ejemplo, si uno piensa que la mejor comprensión de la naturaleza humana y la condición humana es que los humanos son la creación caída del Dios bíblico, entonces uno está naturalmente obligado a establecer datos putativos de creencias sobrenaturales en los que piensan en lo bueno. Grayling admite: “Es posible que las personas religiosas también sean humanistas”[95]; pero inmediatamente califica esta admisión al afirmar que las personas religiosas no pueden ser humanistas ‘sin incoherencias’[96]; aunque inmediatamente retira esta acusación y en su lugar afirma que las personas religiosas no pueden ser humanistas sin ‘rareza, ya que no hay un papel que desempeñar en una ética humanista por su creencia (definitoriamente religiosa) en la existencia de agentes sobrenaturales”[97]. Después de haber detenido a Grayling con respecto a su definición de religión, no tenemos que volver a hacerlo. Sin embargo, podemos observar que Grayling no hace nada para justificar su afirmación de que las creencias religiosas no tienen ningún papel en una ética que se deriva de la mejor comprensión de la naturaleza humana y la condición humana en el mundo real. En cambio, Grayling simplemente parece estar asumiendo que el naturalismo es verdadero y de ahí deducir que el humanismo debe ser naturalista.

Grayling sugiere que nosotros: “Consideremos lo que los humanistas aspiran a ser como agentes éticos”[98]. Dada la cosmovisión del humanista secular naturalista, uno podría preguntarse por qué aspiran a ser agentes éticos (no parece que Nietzsche lo apruebe), o (lo que es más importante) cómo pueden justificar la creencia en conceptos como el bien y el mal, correcto e incorrecto[99]. Grayling ni siquiera menciona estos problemas. Según Grayling, los humanistas no religiosos: “Siempre desean respetar a los demás seres humanos, gustarles, honrar sus esfuerzos y simpatizar con sus sentimientos”[100]. ¡Oh, nueva y valiente palabra que tenga tanta gente! Grayling no dice por qué Neitzsche no cuenta como humanista. Me parece que uno puede ser perdonado por derivar una impresión diferente del resto del libro de Grayling, repleto de acusaciones de retraso intelectual y el deseo de obligar a los creyentes religiosos a contradecir sus conciencias si esto les llevara a meter la nariz en la esfera pública. Y luego Grayling suelta un tañido metafísico, afirmando que: “En todos los casos, el enfoque humanista descansa en la idea de que lo que da forma a las personas es el complejo de hechos sobre la interacción entre las bases biológicas de la naturaleza humana y las circunstancias sociales e históricas de cada individuo”[101]. Se trata de un obstáculo metafísico porque equivale a una negación del libre albedrío libertario, que es un requisito previo para la responsabilidad personal, que es un requisito previo para la ética. Como no soy el profesor Grayling, al menos indicaré un argumento para esta afirmación. ¿Cuál es la diferencia entre una roca golpeándote en la cabeza y yo golpeándote en la cabeza que te lleva a considerar irracional hacer a la roca moralmente responsable, pero racional hacerme moralmente responsable? Si “yo” soy una entidad cuyo comportamiento no está conformado por otra cosa que las interacciones entre los fundamentos biológicos de mi naturaleza humana y mi situación social e histórica, entonces seguramente soy análogo a la roca (que es también una entidad del comportamiento de que está conformado por nada más que interacciones entre su naturaleza física y su entorno físico). Por lo tanto, uno podría concluir que no solo el humanismo puede ser religioso, sino que ese humanismo debería ser religioso en la pena de la autocontradicción.

Conclusión

Estoy de acuerdo con Grayling en que: “Todos los que tengan motivos seguros para sus puntos de vista no deben temer al fuerte desafío y crítica”[102]. Desafortunadamente, Grayling no ofrece casi nada por medio de un compromiso serio con los supuestos motivos de la religión o de su propia “perspectiva no religiosa”. En efecto, Against All Gods (Contra todos los dioses) debe clasificarse como una de las críticas más débiles de la religión jamás publicada. Es francamente decepcionante encontrar a un filósofo profesional, y alguien que exige “que se respeten los estándares de rigor intelectual en todos los niveles educativos”[103], fracasando tan singularmente en manejar el importante tema de la religión con algo que se acerca al rigor intelectual .Grayling sustituye a los hombres de paja, las pistas falsas y los falsos dilemas por la precisión cuidadosa que exige su tema; él sustituye las generalizaciones precipitadas y apresuradas por inferencias basadas en la evidencia; y él sustituye repetidamente la afirmación por argumento. Lo más decepcionante de todo es que Grayling defiende el doble estándar intolerante e independiente que la sociedad debería exigir y aplicar (es decir, hacer cumplir): “Un derecho para el [no religioso] a ser libre de proselitismo”[104], una demanda que lógicamente implica que el cristianismo debe ser ilegal. Lejos de que sea hora de “devolver el compromiso religioso a la esfera privada”[105] –un acto de opresión que solo puede alimentar los fuegos del fundamentalismo religioso– sugiero que ahora, más que nunca, es el momento de alentar el debate respetuoso entre personas con diferentes visiones del mundo en el terreno común de su humanidad compartida. Si un cristiano y un humanista secular no pueden ponerse de acuerdo sobre eso, entonces el futuro parece realmente sombrío. No estoy en desacuerdo con todo lo que Grayling tiene que decir. En particular, aplaudo su recomendación de que: “La idea de las buenas derrotas –aquellas en las que se aprende, o da, o permite que florezca mejor– es una importante”[106].

Artículo original 2007. Revisado 2013.

Recursos recomendados

A.C. Grayling, Against All Gods (Contra todos los dioses), (Oberon Books, 2007)

A.C. Grayling, The Meaning of Things (El Significado de las Cosas), (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2001)

Wikipedia, ‘AC Grayling’ @ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A._C._Grayling

A.C. Grayling y Peter S. Williams, The God Argument (El argumento de Dios): www.bethinking.org/who-are-you-god/advanced/unbelievable-ac-graylings-the-god-argument.htm

John F. Ankerberg (editor), Gary R. Habermas y Antony GN Flew, Resurrected? An Atheist & Theist Dialogue (¿Resucitado? Un diálogo ateo y teísta) , (Rowman y Littlefield, 2005)

Michael J. Behe, Darwin’s Black Box, 2ª edición, (Free Press, 2006)

Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony (Jesús y los testigos presenciales: Los Evangelios como Testimonio de un testigo ocular), (Eerdmans, 2006)

Douglas Geivett y Gary R. Habermas, In Defense of Miracles: A Comprehensive Case for God’s Action in History (En defensa de los milagros: un caso completo para la acción de Dios en la historia), (Apollos, 1997)

Paul Copan y Paul K. Moser (ed.), The Rationality of Theism (La racionalidad del teísmo), (Routledge, 2003)

J.P. Moreland, Scaling the Secular City (Escalando la ciudad secular), (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1987)

J.P. Moreland, Love Your God With All Your Mind: The role of reason in the life of the soul, (Ama a tu Dios con toda tu mente: el papel de la razón en la vida del alma), (Navpress, 1997)

Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief (Creencia Cristiana Garantizada), (Oxford, 2003)

Richard Swinburne, The Resurrection of God Incarnate (La Resurrección de Dios Encarnado), (Clarendon Press, 2003)

David Beck, “The Cosmological Argument” (El argumento cosmológico) www.4truth.net/fourtruthpbgod.aspx?pageid = 8589952710

Michael Behe, “The Lamest Attempt Yet to Answer the Challenge Irreducible Complexity Poses for Darwinian Evolution” (El intento más débil aún por responder al desafío, la complejidad irreductible plantea para la evolución darwiniana) www.idthefuture.com/2006/04/the_lamest_attempt_yet_to_answ.html

Michael Behe, “Philosophical Objections to Intelligent Design” (Objeciones filosóficas al diseño inteligente) www.arn.org/docs/behe/mb_philosophicalobjectsresponse.htm

Paul Copan, “The Moral Argument for God’s Existence” (El argumento moral para la existencia de Dios) www.4truth.net/fourtruthpbgod.aspx?pageid = 8589952712

William Lane Craig, “The existence of God and the Beginning of the Universe” (La existencia de Dios y el comienzo del universo) www.leaderu.com/truth/3truth11.html

William Lane Craig, “Contemporary Scholarship and the Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus” (Becas contemporáneas y la evidencia histórica de la resurrección de Jesús) www.leaderu.com/truth/1truth22.html

William Lane Craig, “The Problem of Miracles: A Historical and Philosophical Perspective” (El problema de los milagros: una perspectiva histórica y filosófica) www.leaderu.com/offices/billcraig/docs/miracles.html

William Lane Craig, “The Indispensability of Theological Meta-Ethical Foundations for Morality” (La indisponibilidad de los fundamentos meta-éticos teológicos para la moral), www.leaderu.com/offices/billcraig/docs/meta-eth.html

Gary R. Habermas, “Why I Believe the New Testament is Historically Reliable” (Por qué creo que el Nuevo Testamento es históricamente confiable) http://www.apologetics.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=165:why-i-believe-

Gary R. Habermas, “The Lost Tomb of Jesus: A Response” (La tumba perdida de Jesús: una respuesta) www.garyhabermas.com/articles/The_Lost_Tomb_of_Jesus/losttombofjesus_response.htm

Video: Robert C. Koons, “Science and Belief in God: Concord not Conflict” (Ciencia y creencia en Dios: La Concordia no Conflicto) http://webcast.ucsd.edu:8080/ramgen/UCSD_TV/7828.rm

Robert C. Koons, “A New Look at the Cosmological Argument” (Una Nueva Mirada al Argumento Cosmológico) www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/philosophy/faculty/koons/cosmo.pdf

Art Lindsley, “C.S. Lewis on Chronological Snobbery” (C.S. Lewis sobre el esnobismo cronológico) www.cslewisinstitute.org/webfm_send/596

J.P. Moreland, “The Historicity of the New Testament” (La historicidad del Nuevo Testamento) www.bethinking.org/resource.php?ID = 207 & TopicID = 1 & CategoryID = 2

Video: J.P. Moreland, “Righ and Wrong as a Key to the Meaning of the Universe” (Correcto e incorrecto como clave del significado del universo) http://youtu.be/p7OKfQajrxs

Stephen C. Meyer, “Intelligent Desing is not Creationism” (El diseño inteligente no es creacionismo) www.discovery.org/scripts/viewDB/index.php?command = view & id = 3191

Tom Price, “Faith is just about ‘trusting God’ isn’t it?” (La fe se trata solo de” confiar en Dios “¿no es así?) www.bethinking.org/resource.php?ID = 132 & TopicID = 9 & CategoryID = 8

Alexander R. Pruss, “A Restricted Principle of Sufficient Reason and the Cosmological Argument” (Un principio restringido de razón suficiente y el argumento cosmológico) www.georgetown.edu/faculty/ap85/papers/RPSR.html

John G. West, “Intelligent Desing and Creationism are Just not the Same” (El diseño inteligente y el creacionismo no son lo mismo) www.discovery.org/scripts/viewDB/index.php?command = view & id = 1329

Audio: Peter S. Williams, “The Moral Argument” (El argumento moral) www.damaris.org/cw/audio/williams_on_dawkins_moral_argument.mp3

Notas

[1] A.C. Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 7.

[2] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 37.

[3] cf. Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief, (Oxford, 2003)

[4] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 37.

[5] Scott A. Shalkowski, “Atheological Apologetics” en R. Douglas Geivett y Brendan Sweetman (ed.), Contemporary Perspectives on Religious Epistemology (Oxford, 1992), p. 66.

[6] William L. Rowe, ‘The Problem of Evil and Some Varieties of Atheism’, American Philosophical Quarterly 16 (1979).

[7] A.C. Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 29.

[8] Eric S. Waterhouse, The Philosophical Approach to Religion (Epworth Press, 1933), p 20.

[9] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 9-10.

[10] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 31.

[11] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 13.

[12] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 9.

[13] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 18.

[14] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 9.

[15] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 30.

[16] Philip J. Sampson, Six Modern Myths Challenging Christian Faith, (IVP, 2000), p. 133.

[17] William Monter, Ritual, Myth and Magic in Early Modern Europe (Brighton: Harvester, 1983), p. 67.

[18] Hugh Trevor-Roper, The European Witch-Craze of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, (Penguin, 1969), p. 37.

[19] Keith Ward, Is Religion Dangerous? (Lion, 2006), p. 7.

[20] ibid, p. 35.

[21] William Wilberforce, citado por Louis Palau, Is God Relevant? (Hodder y Stoughton, 1997), p. 185.

[22] Richard Norman, On Humanism, p. 17.

[23] Tom Price, ‘Can you teach old dog new tricks?’ @ http://abetterhope.blogspot.com/2007/03/can-you-teach-old-dog-new-tricks.html

[24] A.C. Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 15-16.

[25] J.P. Moreland, Love Your God With All Your Mind, (NavPress, 1997), p. 122.

[26] C.S. Lewis, quoted by Norman L. Geisler in the foreword to J.P. Moreland’s Scaling the Secular City (Baker, 1987).

[27] Tom Price, ‘Faith is just about “trusting God” isn’t it?’@ www.bethinking.org/resource.php?ID = 132 & TopicID = 9 & CategoryID = 8

[28] Norman L. Geisler y Paul D. Feinberg, lntroduction to Philosophy – A Christian Perspective (Baker, 1997), p. 73.

[29] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 26.

[30] John Gray, ‘Sex, Atheism and Piano Legs’ in Heresies: Against Progress and Other Illusions’, (Granta, 2004), p. 45.

[31] ibid, p. 46.

[32] Piers Benn, ‘Is Atheism a Faith Position?’ Think, issue thirteen, summer 2006, p. 29.

[33] James Lazarus, ‘A reconsideration of some atheistic arguments’ (Una reconsideración de algunos argumentos ateos) @ www.iidb.org/vbb/showthread.php?t = 181970

[34] Nigel Warburton, Pensando: De la A a la Z, Segunda Edición, (Routledge, 1998), p. 19.

[35] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 46.

[36] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 36.

[37] cf. Richard Bauckham, Jesús y los testigos oculares: Los Evangelios como Testimonio de un testigo ocular, (Eerdmans, 2006); Richard Baukham, “Los testigos oculares y las tradiciones evangélicas” @ www.apollos.ws/nt-historical-reliability/BauckhamRichardJHRG1.pdf

[38] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 43.

[39] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 45.

[40] Keith Ward, ‘Evidence for the Virgin Birth’ en Gilliam Ryeland (ed.), Beyond Reasonable Doubt , (The Canterbury Press, 1991), pág. 56-57.

[41] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 28.

[42] A.C. Grayling, El significado de las cosas, (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2001), p. 125.

[43] Ward, “Evidence for the Virgin Birth” en Gilliam Ryeland (ed.), Beyond Reasonable Doubt, (The Canterbury Press, 1991), pág. 60.

[44] A.C. Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 34.

[45] Art Lindsley, “C.S. Lewis sobre el esnobismo cronológico” @ www.cslewisinstitute.org/pages/resources/publications/knowingDoing/2003/LewisChronologicalSnobbery.pdf

[46] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 28.

[47] Grayling, Against All Gods, (Oberon Books, 2007), p. 28-29.

[48] cf. Peter S. Williams, ‘Un Cambio de Mente para Antony Flew’ @ www.arn.org/docs/williams/pw_antonyflew.htm

[49] Antony Flew, La presunción del ateísmo, (Londres: Pemberton, 1976), p. 14.

[50] Copán, “La presuntuosidad del ateísmo” @ www.rzim.org/publications/essay_arttext.php?id = 3

[51] Scott A. Shalkowski, ‘Atheological Apologetics’ en R. Douglas Geivett y Brendan Sweetman (ed.), Contemporary Perspectives on Religious Epistemology , (Oxford, 1992), p. 63.

[52] cf. Stephen C. Meyer, “El diseño inteligente no es creacionismo” @ www.discovery.org/scripts/viewDB/index.php?command = view & id = 3191 ;

John G. West, ‘Diseño inteligente y creacionismo no son lo mismo’ @ www.discovery.org/scripts/viewDB/index.php?command = view & id = 1329

[53] cf. Michael Behe, “Objeciones filosóficas al diseño inteligente” @ www.arn.org/docs/behe/mb_philosophicalobjectsresponse.htm ; ‘¿ El diseño inteligente es meramente y el argumento forma ignorancia?’@ www.ideacenter.org/contentmgr/showdetails.php/id/1186

[54] En el documento científico al que hace referencia Grayling (páginas 49, 51 y 52), cf. Michael Behe, “El intento más débil aún por responder al desafío, la complejidad irreductible se presenta para la evolución darwiniana” @ www.idthefuture.com/2006/04/the_lamest_attempt_yet_to_answ.html