By Steven Dunn

The conception of the objective reality of elementary particles has not evaporated in the cloud of a new concept of reality, but in the transparent clarity of mathematics which no longer represents the behavior of particles, but our knowledge of this behavior. (W. Heisenberg, 1958) [1]

In this post, I want to focus on the phenomenon of consciousness with respect to quantum mechanics. More specifically, the latest 20th century perspectives on the role of the perceptive mind in quantum mechanics. As Varadaja V. Raman writes in his essay in The Journal of Cosmology (2009), “The disembodied soul goes elsewhere, perhaps to a space that transcends scope and moment. This view of the soul is satisfactory in explaining the phenomenon of dynamic life and nonliving death on a subjective level, but it does not constitute a scientific theory” [2] .

Varadaja Raman’s statement can be seen as an interesting pretext in connection with certain minor philosophical discussions of the physical universe; however, even though Raman here is discussing certain theories applied to the phenomenon of consciousness (e.g. quantum mechanical consciousness, evolution, neuroscience, etc.), Hans Reichenbach (1958) shows how philosophical problems can be brought into scientific interest by using the Euclidean geometrical system. An example:

The problem of the demonstrability of a science was solved by Euclid insofar as he had reduced science to a system of axioms. But now the epistemological question arose of how to justify the truth of these first assumptions. If the certainty of the axioms was transferred to the theorems obtained by means of the system of logical concatenations, the problem of the truth of this involved construction was transferred, in the opposite form, to the axioms. It is precisely the affirmation of the truth of the axioms that sums up the problem of scientific knowledge, once the connection between axioms and theorems has been made. [3]

Thus, as seen throughout your book, philosophy has a certain degree of relevance to questions about the physical universe [4] . As Bernard d’Espagnat (2006) once said: “The great philosophical puzzles lie at the core of present-day physics” [5] . However, the particular interest I have in that matter is how our own perceptual abilities and quantum mechanics have changed our understanding of materialist explanations “from the atom” to the mind having some role in the discussion (if not a fundamental role – the question of course, is “how fundamental?”).

First conscious

As far as the literature regarding this question of consciousness and quantum mechanics goes, a lot of philosophers and physicists over the past few months have really sparked quite an interest in me in asking about the most fundamental philosophical questions about the universe. For example, is the mind fundamental to the universe? Is there something more fundamental than space-time that could actually underlie it? Are there inherent anthropic properties within our universe that would challenge certain evolutionary cosmogonic models? These questions and more related to them are not particularly what I wish to address, but rather the role of the mind as it relates to quantum mechanics. Showing the relationship – or interest – between the two I think would constitute some pertinent criticism concerning materialist interpretations of consciousness.

For now, let us consider a problem relevant to our discussion to be the following: If quantum mechanics is universally correct (and we would like to think so), then we should be able to apply it to the entire universe in order to find its wave function [6] . In this way, we could see which events are probable and which are not. However, certain paradoxes seem to emerge (Linde, 2004) once we try to do so. For example, the Wheeler-DeWitt equation (or, the Shrodinger equation [7] for the wave function of the universe) has a function that does not depend on time – therefore, the evolution of the universe by appeal to its wave function would show that the universe does not change in time.

I was interested in Andrei Linde’s (2004) comment on this topic when he said that “we are not really asking why the universe as a whole is evolving. We are trying to understand our own experimental data. Therefore, a more precisely formulated question is why do we see the universe evolving in time in a certain way?” [8] Linde goes on to say:

Most of the time, when discussing quantum cosmology, one can remain entirely within the boundaries set by purely physical categories, regarding an observer simply as an automaton, and not dealing with questions of whether he/she/it is conscious or not conscious during the process of observation. This limitation is harmless for many practical purposes. But we cannot rule out the possibility that carefully avoiding the concept of consciousness in quantum cosmology may lead to an artificial narrowing of our perspective. [9]

This makes perfect sense with respect to earlier 20th-century commitments to a mechanistic understanding of the universe. As Henry P. Stapp (2009) acknowledged in his essay “Quantum Reality and Mind”: “The dynamical laws of classical physics are formulated entirely in terms of physically described variables: in terms of the quantities that Descartes identifies as elements of the “ res extensa.” Descartes psychologically and complementary describes the elements, things, of his res cogitans as being completely outside themselves: there is, in the causal dynamics of classical physics, no trace of their existence . ” [10]

Thus, our own mental realities have the ability to know about certain physically described properties, but have no way of affecting them in any way” – thus leaving man as an “independent observer”. However, “Quantum physics revealed an inevitable interaction between the observer and the observed in the microcosm. Thus, human consciousness entered the field of physics” [11] . Henry Stapp makes a remarkable comment regarding this shift in thinking:

In view of this fundamental re-entry of mind into basic physics, it is almost incomprehensible that few non-physical philosophers and scientists entertain today, more than eight decades after the downfall of classical physics, the idea that the physicalist conception of nature, based on invalidated classical physical theory, may be deeply flawed in ways highly relevant to the mind-matter problem. [12]

Although it could certainly be expounded in other articles, I would personally favor Stapp’s position regarding a dualistic account of quantum mechanics (“von Neumann Dualistic Quantum Mechanics”), since in my opinion it has the best account of the ontological character of physical reality in quantum mechanics and the relevance of mental reality to the physical (idealistic theories in my opinion fall under the same fault line as Berkeley’s system, and materialistic theories are wanting, so dualism I think does the best).

What have we learned?

Materialism understood within the framework of physics fails once we understand the quantum association of the “observer.” Once we integrate certain Aristotelian terms regarding the ontological character of the physical reality of quantum mechanics (i.e., “potentia” and “actual”), we see that physical reality has the ontological character of potentia— “ As such, it is more mind than matter in character” [13] . Therefore, mental realities cannot be completely revoked under the umbrella of materialism in quantum mechanics.

Grades

[1] Werner Heisenberg, The Representation of Nature in Contemporary Physics . Daedalus, 87 (summer), 95-108.

[2] Varadaja V. Raman, Four Perspectives on Consciousness . Journal of Cosmology (2009, vol. 3) p. 558

[3] Hans Reichenbach, The Philosophy of Space and Time , trans. Maria Reichenbach and John Freud (Dover Books: 1958) pp. 1-2

[4] I would also look at Reichenbach’s chapter on “The Difference Between Space and Time” (p. 109) for more of what I want to say on this topic. For example, the first sentence reads: “The philosophy of science has examined problems of time much less than problems of space.” Further down he explains that while space might be associated with a geometric-Euclidean example, time cannot really be afforded the same courtesy (cf. contrasted from earlier discussions of space, Reichenbach writes that “it is impossible to distinguish between straightness and curvature” with respect to questions of time). Reichenbach there ends: “Thus time lacks, by its one-dimensionality, all the problems that have led to the philosophical analysis of problems of space” (p. 109).

[5] Bernard d’Espagnat, On Physics and Philosophy (Princeton University Press: 2006) p. 2

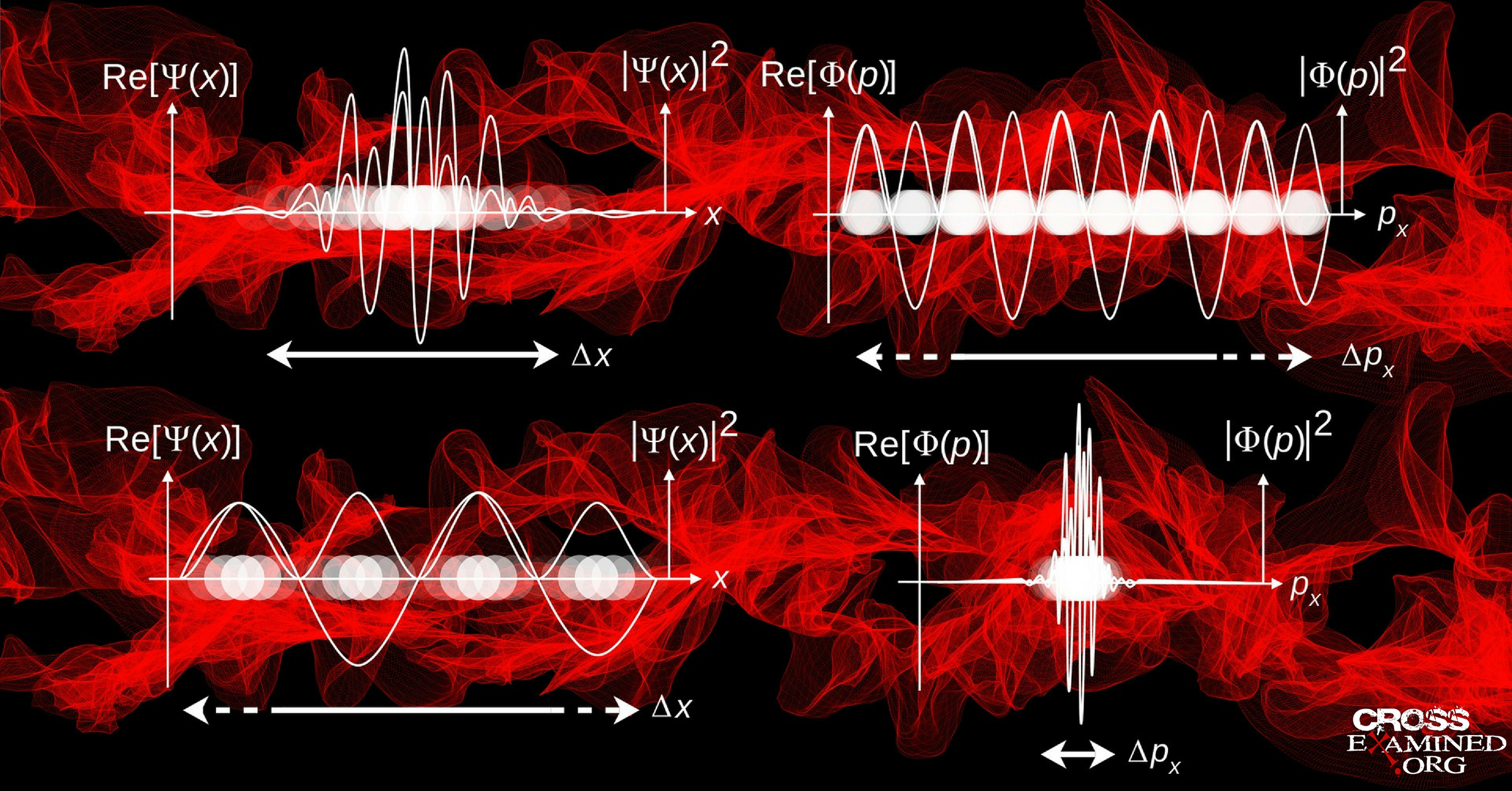

[6] In quantum mechanics, with a built-in principle known as the uncertainty principle, particles do not have “definitively” fixed positions or velocities, but rather states that can be represented by what is known as a wave function. According to Hawking (2001), “A wave function is a number at each point in space that gives the probability that the particle is located at that position” ( Universe in a Nutshell , p. 106).

[7] The Shrödinger equation (taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schr%C3%B6dinger_equation ): This equation tells us the rate at which the wave function changes with time (see Hawking 2001, p. 107–110). Subhash Kak (2009) also makes the interesting statement that “although the evolution of the quantum state is deterministic (given by the Shrodinger equation) its observation results from a collapse of the state into one of its components, in a probabilistic manner.” (See Penrose 2009, pp. 4–5).

[8] Andrei Linde, quoted from The Mystery of Existence , ed. John Leslie and Robert Lawrence Kuhn (Wiley-Blackwell: 2013) p. 162

[9] Ibid.

[10] Henry P. Stapp, cited from Quantum Physics of Consciousness , ed. Roger Penrose (Cosmology Science Publishers: 2009) p. 17

[11] Varadaja Raman (2009), in Quantum Physics of Consciousness , p. 89-90 – emphasis mine.

[12] Henry Stapp (2009), p. 19

[13] Stapp (2009), p. 20

Translated by Jairo Izquierdo