Is Learning Apologetics like Fiddling While Rome Burns?

A Modern Commentary of C.S. Lewis’ ‘Learning in Wartime’

Today it is easy to see why many Christians may be discouraged and feel the need to “circle the wagons,” – to not see the need to cultivate a life of the mind, including learning apologetic arguments for Christianity, or even learning anything new at all. We now live in a world of ISIS, Ebola, violent Christian persecution in various parts of the world, and an increasing attack on religious liberties in America.

Perhaps a lesson from the past will bring light and even encouragement to the value of learning – especially loving Christ with all of our minds in the Church today.

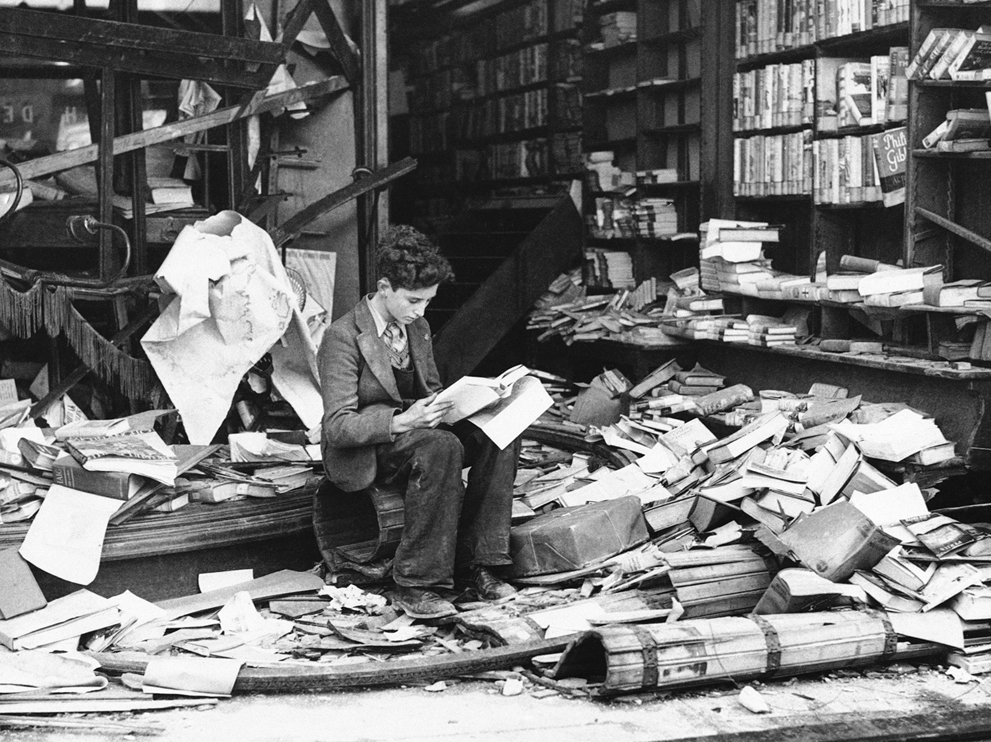

In 1939 the dark clouds of Hitler’s Nazi war machine were beginning to loom across Europe and in England. Walter Hooper, who briefly served as C.S. Lewis’ personal secretary in 1963 relates a fascinating story of when Lewis was invited to preach a sermon at Oxford’s Church of St. Mary the Virgin in the late 30’s.

The threat of imminent war with Germany caused many of Oxford’s undergraduates much hesitation and unrest. Christian students understandably wondered at the value of education and the pursuit of truth when a world war loomed on the horizon. At that time Canon T.R. Milford, an admirer of Lewis’ literary works, asked him to come deliver a sermon and address this growing sentiment among the student body. According to Hooper, “Lewis – an ex-soldier [in WWI] and Christian don at Magdalen College – was thought to be just the man to put things in the right perspective.”[1]

How very right Canon Milford was! Not only did Lewis brilliantly make the case for learning in a time of global upheaval in the twentieth century, there are brilliant lessons we can learn for our own day as well. The text of Lewis’ sermon ended up as a chapter in The Weight of Glory[2] under the title “Learning in Wartime.” The barbarities of our own day and Lewis’s are uncanny, and the lessons are timeless.

Of course, there is no substitute for reading the entire chapter by Lewis’ himself, but in this article, I would like to highlight a few principles that I believe relate to those of us today who traffic in the realm of the mind, ideas, and the intellect.

There has Never Been a Perfect Time to Learn: Favorable Conditions Never Come

If we’re waiting for more peaceful or favorable times [whatever that is] to begin to dig deeper into our faith or perhaps to learn something new, then we’ll probably never begin at all. Lewis knew then that there will always be distractions which prevent us from pursing truth on a deeper level – whether those distractions are the threat of war, or the hectic busyness of life. He writes:

There will always be plenty of rivals to our work. We are always falling in love or quarrelling, looking for jobs or fearing to lose them, getting ill and recovering, following public affairs. If we let ourselves we shall always be waiting for some distraction or other to end before we can really get down to our work. The only people who achieve much are those who want knowledge so badly that they seek it while the conditions are still unfavorable. Favorable conditions never come.[3]

…If men had postponed the search for knowledge and beauty until they were secure, the search would never have begun. We are mistaken when we compare war with “normal life.” Life has never been normal.[4]

If we will not pursue truth and cultivate loving God with our minds with today’s many threats and distractions, then we probably never will. Life has never been “normal.”

Shouldn’t We Just Preach the Gospel Only?

There were those in Lewis’ day (as well as our own) who perhaps thought that learning should take a back-seat to leading people to Christ in evangelism.

..how is it even right, or even psychologically possible, for creatures who are every moment advancing either to Heaven or to hell spend any fraction of the little time allowed them in this world on such comparative trivialities as literature or art, mathematics or biology.[5]

…why should we – indeed how can we – continue to take an interest in these placid occupations when the lives or our friends and the liberties of Europe are in the balance? Is it not fiddling while Rome burns?[6]

Or,

“How can you be so frivolous and selfish as to think about anything but the salvation of human souls?” and we have, at the moment to answer the additional question, “How can you be so frivolous and selfish as to think of anything but the war?”[7]

Of course, in saying these things Lewis is certainly not undermining the importance of personal evangelism. Indeed, several years later in that same chapel, he preached what is perhaps, one of the most profound sermons on evangelism ever preached in the 20th Century [at least in my opinion!].

The load, or weight, or burden of my neighbor’s glory should be laid on my back, a load so heavy that only humility can carry it, and the backs of the proud will be broken. …All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct our dealings with one another…[8]

Lewis’ solution to this apparent dilemma of either evangelism (the active life), or learning (the contemplative life), is that whatever our view of this relationship is during peacetime, should be the exactly the same as in a time of war.

Now it seems to me that we shall not be able to answer these questions until we have put them by the side of other questions which every Christian ought to have asked himself in peacetime.

During a time of peace hardly any Christian doubts the value of loving God with all our minds and cultivating a deeper Christian understanding and integration of reality. So why should our principles change during a time of imminent death and war? According to Lewis, they shouldn’t.

In other words, regardless of whether we are living in a time of impending war & violence or relative peace and safety, there is an important place for both activities in the Christian view of things.

We don’t have to choose either evangelism or learning – it is imperative to do both!

Lastly, on this question, Lewis makes it clear that he makes no distinctions between the secular and the sacred.

Every duty is a religious duty, and our obligation to perform every duty is therefore absolute.[9]

In short, ‘whether we eat or drink, [do evangelism, or learn], or whatever we do, we do it all for the glory of God (1 Cor. 10:31).’

In Our Pursuit of Truth, there is No Place for the Proud

Christ was very clear when He stated the greatest commandment, “to love the Lord your God with all of your heart, soul, mind, and strength” (Matt. 22:36). Lewis recognized that a life of learning is perhaps not the path for every Christian. Indeed, within the body of Christ, there are many members with different functions (1 Cor. 12:12-31).

Regardless, our pursuit and love of the pure, unvarnished truth should take second place to our pride and personal achievements (if any). We must always be on guard against pride, whatever our vocation, but especially intellectual pride – for as the Apostle Paul writes, “…knowledge puffs up, but love builds up” (1 Cor. 8:1). Lewis writes:

As the author of the Theologica Germanica says, we may come to love knowledge – our knowing – more than the thing known: to delight not in the exercise of our talents but the fact that they are ours, or even in the reputation they bring us. Every success in the scholar’s life increases this danger. If it becomes irresistible, he must give up his scholarly work. They time for plucking out the right eye has arrived.[10]

In apologetics as in any other intellectual pursuit, there is no place for pride, whatever form it takes in our lives. We are servants of Truth and not the other way around.

…be ready to give a defense [apologia] to everyone who asks you a reason [logos] for the hope that is in you, with meekness and fear (1 Pet. 3:15).

I can’t tell you how many apologists I’ve noticed, who are arrogant and condescending to others who don’t have a deeper understanding. This certainly does not help the cause of Christ or His Kingdom, and in reality, intellectual pride is the mark of another kingdom. The father of pride led a rebellion of a third of the angels against God. In Eden, he convinced Adam & Eve that God did not say what He really said.

Don’t Worry About the Future – Live Life One Day at a Time

One of the frustrations that Lewis addressed to his audience of Oxford undergraduates in 1939 was the frustration of possibly not being able to finish what one has started – of looking ahead to the future when it looks bleak. “What’s the point?”

This is certainly a sentiment that is true today. When one thinks of the future of the world and where we might be headed, it can be somewhat foggy or even depressing. Lewis’ wisdom is especially brilliant here because it is grounded in the very words of Christ’s Sermon on the Mount (see, Matt. 6:34).

Lewis states:

Never, in peace or war, commit your virtue or happiness to the future. Happy work is best done by the man who takes his long-term plans somewhat lightly and works from moment to moment “as unto the Lord.” It is only our daily bread that we are encouraged to ask for. The present is the only time in which any duty can be done or any grace received. …A more Christian attitude, which can be attained in any age, is that of leaving futurity in God’s hands. We may as well, for God will certainly retain it whether we leave it to Him or not.[11]

Human Civilization Depends on Not Listening to Our Worries but on Thinking Clearly and Loving God with our Minds

Finally, in the larger scheme of human history, we should not allow our worries to dictate how we live. Human culture (if it is to survive) depends on it. Lewis writes:

If human culture [& learning] can stand up [and alongside] to that [that people today are headed to eternity in heaven or hell], it can stand up to anything. To admit that we can retain our interest in learning under the shadow of these eternal issues but not under the shadow of a European war would be to admit that our ears are closed to the voice of reason and very wide open to the voice of our nerves and our mass emotions.[12]

Here we can learn from a chapter in the history of the early, medieval Irish monks. When the British Isles were under the threat and then eventually under the sword of the Norsemen, Irish Christians didn’t worry & fret about their future. Rather, they went to work translating great works of literature and creating great works of art such as we find in the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels.

In his book, How the Irish Saved Civilization, author Thomas Cahill narrates in vivid detail the fall of the Roman empire when barbarian hordes marched across the frozen Rhine and eventually down into Italy ultimately sacking Rome herself, the crown jewel of classical civilization and learning. Several centuries later when the prow of the Viking longboat hit the sands of the British Isles another dark ages swept across Europe. Civilization was threatened and the learning of the classical world was gravely threatened.

It was the Irish Christians, who according to Cahill, played a key role in Europe’s rebuilding after the long and dark ages.

Wherever they went the Irish bought with them their books, many unseen in Europe for centuries and tied to their waists as signs of triumph, just as Irish heroes had once tied to their waists their enemies heads. Wherever they went they brought their love of learning and their skills in bookmaking. In the bays and valleys of their exile, they reestablished literacy and breathed new life into the exhausted literary culture of Europe. And that is how the Irish saved civilization.[13]

It is in light of these and other principles, that we pursue Truth for its own sake, we learn apologetic arguments, we love God with our minds, and we cultivate a life of faith grounded in God’s eternal Word.

Eternal things are at stake.

[1] Walter Hooper, “Introduction,” in C.S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory (New York: Harper One, 2000, originally 1949), pg. 18.

[2] Incidentally, the title of Lewis’ second message at The Church of St. Mary the Virgin at Oxford in 1941.

[3] Lewis, “Learning in Wartime,” pg. 60.

[4] Ibid., pg. 49.

[5] Ibid., 48-9.

[6] Ibid., pg.47.

[7] Ibid, pg. 50-1.

[8] The Weight of Glory, pg. 45-6.

[9] “Learning in Wartime,” pg. 53.

[10] “Learning in Wartime,” pg. 57.

[11] “Learning in Wartime,” pg. 60-61.

[12] Ibid.. pg. 49.

[13] Thomas Cahill, How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland’s Historic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe (New York, London: Doubleday, 1995), pg. 196.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!