By Erik Manning

There’s a dizzying array of arguments for the existence of God. For a newbie looking to get into apologetics, it can be intimidating trying to figure out where to start. You have the cosmological argument, but it helps if you know something about cosmology, physics, and even math. There’s the argument from the origin of life, but now you’re talking about chemistry, DNA, information theory, and it can feel overwhelming. There’s the ontological argument, but that requires understanding modal logic and let’s be real here, has anyone in the history of the universe come to faith because of the ontological argument? Sorry, St. Anselm.

If you’re looking either for ammo to argue against naturalistic atheism or to give some reasons for someone to think God exists, I wholeheartedly recommend learning the moral argument. Why?

For one thing, it’s accessible. You don’t need a Ph.D. in philosophy, physics, or chemistry to understand the argument. Secondly, it’s more effective because it touches people at a personal level that scientific arguments do not.

Dr. William Lane Craig earned his doctorate in philosophy and spent decades developing a version of the cosmological argument. But after spending years of traveling, speaking, teaching and debating some of the smartest atheists on the planet, here’s what he has to say about the moral argument:

““In my experience, the moral argument is the most effective of all the arguments for the existence of God. I say this grudgingly because my favorite is the cosmological argument. But the cosmological and teleological (design) arguments don’t touch people where they live. The moral argument cannot be so easily brushed aside. For every day you get up you answer the question of whether there are objective moral values and duties by how you live. It’s unavoidable.”

-On Guard, Chapter 6

With a little thought, you know this is true. Just log on to Twitter or turn on cable news for a few seconds. We live in a culture where people are in a state of constant moral outrage. CS Lewis popularized the argument in his classic work Mere Christianity. (Warning: Massive understatement alert!) In regards to the power of the moral argument, Lewis says:

“We have two bits of evidence about the Somebody. One is the universe He has made. If we used that as our only clue, then I think we should have to conclude that He was a great artist (for the universe is a very beautiful place), but also that He is quite merciless and no friend to man (for the universe is a very dangerous and terrifying place). The other bit of evidence is that Moral Law which He has put into our minds.

And this is a better bit of evidence than the other because it is inside information. You find out more about God from the Moral Law than from the universe in general just as you find out more about a man by listening to his conversation than by looking at a house he has built. Now, from this second bit of evidence, we conclude that the Being behind the universe is intensely interested in right conduct—in fair play, unselfishness, courage, good faith, honesty, and truthfulness.“

So what is the moral argument? You can cash it out in different ways, but I favor using it negatively in order to falsify atheism. If atheism isn’t true then obviously we should reject it and find a worldview that makes better sense of reality. Here’s the argument in logical form:

- If naturalistic atheism is true, there are no moral facts.

- There are moral facts.

- Therefore, naturalistic atheism is false.

An example of a moral fact would be that even if NAMBLA (North American Man/Boy Love Association…ew.) somehow hypnotized the world into thinking that pedophilia is morally acceptable, it would still be morally wrong. Morality isn’t a matter of personal preference. I’m going to bring some ‘hostile witnesses’ on the scene to help make my case.

CAN MORAL FACTS BE FACTS OF NATURE?

Some atheists have tried to say so, but I think unsuccessfully. Moral facts aren’t about the way things are, but the way things ought to or should be. But if the world isn’t here for a purpose, then there is no way things are intended to be. Natural facts are facts about the way things are, not the way things ought to be. Animals kill and forcibly mate with other animals, but we don’t call those things murder or rape. But if natural facts are the only types of facts on the table, then the same holds true of people. We can explain the pain and suffering on a scientific level, but we can’t explain why one ought not to inflict suffering and pain.

Here are three atheists who drive the point home that on atheism there can be no moral facts.

Michael Ruse

“The position of the modern evolutionist…is that humans have an awareness of morality…because such an awareness is of biological worth. Morality is a biological adaptation no less than our hands and feet and teeth… Considered as a rationally justifiable set of claims about an objective something, ethics is illusory. I appreciate that when somebody says “Love thy neighbor as thyself,” they think they are referring above and beyond themselves…Nevertheless, such reference is truly without foundation. Morality is just an aid to survival, and reproduction…and any deeper meaning is illusory.” – Atheist philosopher Michael Ruse.

“In a universe of blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it or any justice. The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference. DNA neither knows nor cares. DNA just is.“ – Atheist biologist Richard Dawkins

And finally, here’s atheist philosopher Alex Rosenberg, when asked about the cruel and inhumane cultural practice of foot-binding that was practiced by the Chinese for centuries:

Interviewer: “And so your argument is to say we shouldn’t do foot-binding anymore because it’s not adaptive, or should we…?”

Rosenberg: “No. I don’t think that it is in a position to tell you what we ought and ought not to do: it is in a position to tell you why we’ve done it and what the consequences of continuing or failing to do it are, okay? But it can’t adjudicate ultimate questions of value, because those are expressions of people’s emotions and, dare I say, tastes.”

Earlier in the interview, Rosenberg says, “Is there a difference between right and wrong, good and bad? There’s not a moral difference between them.”

A matter of tastes?

BUT THERE ARE MORAL FACTS

So rather than giving up naturalism, these atheists bite the bullet and say that on their worldview there is no room for moral facts. But how plausible is that really? As you can imagine, many atheists disagree. Here are some more ‘hostile witnesses’ I’ll bring in to make the point:

“Whatever skeptical arguments may be brought against our belief that killing the innocent is morally wrong, we are more certain that the killing is morally wrong than that the argument is sound…Torturing an innocent child for the sheer fun of it is morally wrong. Full stop.” -Atheist philosopher Paul Cave.

“Some moral views are better than others, despite the sincerity of the individuals, cultures, and societies that endorse them. Some moral views are true, others false, and my thinking them so doesn’t make them so. My society’s endorsement of them doesn’t prove their truth. Individuals and whole societies can be seriously mistaken when it comes to morality. The best explanation of this is that there are moral standards not of our own making.” – Atheist philosopher Russ Shafer-Landau

Louise Antony

“Any argument for moral skepticism will be based upon premises which are less obvious than the existence of objective moral values themselves.” – Atheist philosopher Louise Antony

This makes sense. Any argument that allows for the possibility that there is no more moral virtue in adopting a child or torturing a child for fun is a lot less plausible than the existence of moral values and duties. Why should we doubt our moral sense any more than our physical senses?

The problem is for the naturalist is that from valueless, meaningless processes valueless, meaninglessness comes. Atheism just doesn’t seem to have the resources for the existence of moral facts. Christian philosopher Paul Copan writes:

“Intrinsically-valuable, thinking persons do not come from impersonal, non-conscious, unguided, valueless processes over time. A personal, self-aware, purposeful, good God provides the natural and necessary context for the existence of valuable, rights-bearing, morally-responsible human persons.”

And atheist philosopher JL Mackie agrees that if there are moral facts, their existence fits much better on theism than on atheism. He wrote “Moral properties constitute so odd a cluster of properties and relations that they are most unlikely to have arisen in the ordinary course of events without an all-powerful god to create them. If there are objective values, they make the existence of a god more probable than it would have been without them. Thus, we have a defensible argument from morality to the existence of a god.”

THE POWER OF THE MORAL ARGUMENT: HOW 3 FORMER ATHEISTS CHANGED THEIR MINDS

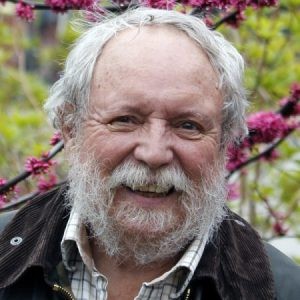

Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health and formerly led the Human Genome Project

Dr. Francis Collins

Dr. Collins was an atheist until he read Lewis. In his book The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief, he writes:

“The argument that most caught my attention, and most rocked my ideas about science and spirit down to their foundation, was right there in the title of Book one: “Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe.” While in many ways the “Moral Law” that Lewis described was a universal feature of human existence, in other ways it was as if I was recognizing it for the first time.

To understand the Moral Law, it is useful to consider, as Lewis did, how it is invoked in hundreds of ways each day without the invoker stopping to point out the foundation of his argument. Disagreements are part of daily life. Some are mundane, as the wife criticizing her husband for not speaking more kindly to a friend, or a child complaining, “It’s not fair,” when different amounts of ice cream are doled out at a birthday party. Other arguments take on larger significance. In international affairs for instance, some argue that the United States has a moral obligation to spread democracy throughout the world, even if it requires military force, whereas others say that the aggressive, unilateral use of military and economic force threatens to squander moral authority.

In the area of medicine, furious debates currently surround the question of whether or not it is acceptable to carry out research on human embryonic stem cells. Some argue that such research violates the sanctity of human life; others posit that the potential to alleviate human suffering constitutes an ethical mandate to proceed.

Notice that in all these examples, each party attempts to appeal to an unstated higher standard. This standard is the Moral Law. It might also be called “the law of right behavior,” and its existence in each of these situations seems unquestioned. What is being debated is whether one action or another is a closer approximation to the demands of that law. Those accused of having fallen short, such as the husband who is insufficiently cordial to his wife’s friend, usually respond with a variety of excuses why they should be let off the hook. Virtually never does the respondent say, “To hell with your concept of right behavior.”

What we have here is very peculiar: the concept of right and wrong appears to be universal among all members of the human species (though its application may result in wildly different outcomes). It thus seems to be a phenomenon approaching that of a law, like the law of gravitation or of special relativity. Yet in this instance, it is a law that, if we are honest with ourselves, is broken with astounding regularity.”

Leah Libresco, graduate of Yale University, political scientist, statistician and popular blogger

Leah Libresco

Leah used to write about atheism on the Patheos network of blogs. She grew up as an atheist but began to doubt her doubts. In her last post on the atheist portal of Patheos, she wrote:

“I’ve heard some explanations that try to bake morality into the natural world by reaching for evolutionary psychology. They argue that moral dispositions are evolutionarily triumphant over selfishness, or they talk about group selection, or something else. Usually, these proposed solutions radically misunderstand a) evolution b) moral philosophy or c) both. I didn’t think the answer was there. My friend pressed me to stop beating up on other people’s explanations and offer one of my own.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I’ve got bupkis.”

“Your best guess.”

“I haven’t got one.”

“You must have some idea.”

“I don’t know. I’ve got nothing. I guess Morality just loves me or something.”

“…”

“Ok, ok, yes, I heard what I just said. Give me a second and let me decide if I believe it.”

It turns out I did.”

“I had one thing that I was most certain of, which is that morality is something we have a duty to, and it is external from us. And when push came to shove, that is the belief I wouldn’t let go of.”

Later in an interview with CNN, she said: “I’m really sure that morality is objective, human independent, and something we uncover like archaeologists, not something we build like architects. And I was having trouble explaining that in my own philosophy, and Christianity offered an explanation which I came to find compelling.”

Dr. Sarah Irving-Stonebraker, Western Sydney University, Senior Lecturer on History and Cambridge graduate

Dr. Sarah Irving-Stonebraker

Irving-Stonebraker wrote an article titled ‘How Oxford and Peter Singer Drove Me From Atheism to Jesus’. Peter Singer is a famous bio-ethicist that is well-respected but has some pretty far-out views. He’s very big into animal rights and has said things like “The notion that human life is sacred just because it is human life is medieval.” Singer has advocated infanticide in certain circumstances, as well as bestiality. Yeah, I know. Only a philosopher could attempt to justify such insanity intellectually. Anyway, here’s Dr. Irving-Stonebraker:

“I grew up in Australia, in a loving, secular home, and arrived at Sydney University as a critic of “religion.” I didn’t need faith to ground my identity or my values. I knew from the age of eight that I wanted to study history at Cambridge and become a historian. My identity lay in academic achievement, and my secular humanism was based on self-evident truths…

After Cambridge, I was elected to a Junior Research Fellowship at Oxford. There, I attended three guest lectures by world-class philosopher and atheist public intellectual, Peter Singer. Singer recognized that philosophy faces a vexing problem in relation to the issue of human worth. The natural world yields no egalitarian picture of human capacities. What about the child whose disabilities or illness compromises her abilities to reason? Yet, without reference to some set of capacities as the basis of human worth, the intrinsic value of all human beings becomes an ungrounded assertion; a premise which needs to be agreed upon before any conversation can take place.

I remember leaving Singer’s lectures with a strange intellectual vertigo; I was committed to believing that universal human value was more than just a well-meaning conceit of liberalism. But I knew from my own research in the history of European empires and their encounters with indigenous cultures, that societies have always had different conceptions of human worth or lack thereof. The premise of human equality is not a self-evident truth: it is profoundly historically contingent. I began to realize that the implications of my atheism were incompatible with almost every value I held dear … One Sunday, shortly before my 28th birthday, I walked into a church for the first time as someone earnestly seeking God. Before long I found myself overwhelmed. At last, I was fully known and seen and, I realized, unconditionally loved – perhaps I had a sense of relief from no longer running from God. A friend gave me C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, and one night, after a couple months of attending church, I knelt in my closet in my apartment and asked Jesus to save me, and to become the Lord of my life”

THE NATURALIST’S DILEMMA

I hope you can see by now that the moral argument is an argument that is pretty difficult to get away from. It forces the skeptic into a few different corners: They either have to:

a.) bite the bullet like Mackie, Ruse, Dawkins, and Rosenberg do and just accept the crazy and counter-intuitive notion that there just are no moral facts at all, no matter how obvious that seems to all of us. Or they can –

b.) accept there are somehow moral facts but have no way to really ground them. Why think valueless, meaningless processes produce beings with intrinsic moral value that have obligations to one another? On atheism, there just is no way things ought to be and morality is about what ought and ought not to be. You could stubbornly dig your heels in here anyway, or –

c.) make the move that Collins, Libresco and Irving-Stonebraker (and myriads of others) did and dump their worldview in exchange for one that can provide more robust resources for why human beings have worth and duties towards one another.

My hope is that you see that the moral argument is effective. Many times it has changed people’s minds. It speaks to people because we’re all moral creatures; we can’t help but make moral decisions and judgments every day. And possibly most importantly, the moral argument shows us that we’ve all fallen short of the moral law and that we need forgiveness. Christianity has plenty to say about redemption and God’s mercy.

For these reasons, if there was one argument for God that I’d recommend you really camp on until you master it, it’s this one.

Recommended Resources:

CS Lewis’ Moral Argument on the YouTube Channel CS Lewis Doodle

Mere Christianity, CS Lewis

God, Naturalism, and The Foundations for Morality, Paul Copan (free)

The Moral Poverty of Evolutionary Naturalism, Mark Linville (free)

A Simple Explanation of the Moral Argument, Glenn Peoples (free)

Erik Manning is a former atheist turned Christian after an experience with the Holy Spirit. He’s a freelance baseball writer and digital marketing specialist who is passionate about the intersection of evangelism and apologetics.

Original Blog Source: http://bit.ly/2QvLvni